- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychotherapy with Older Adults

About this book

This Third Edition of the bestselling Psychotherapy with Older Adults continues to offer students and professionals a thorough overview of psychotherapy with older adults. Using the contextual, cohort-based, maturity, specific challenge (CCMSC) model, it draws upon findings from scientific gerontology and life-span developmental psychology to describe how psychotherapy needs to be adapted for work with older adults, as well as when it is similar to therapeutic work with younger adults. Sensitively linking both research and experience, author Bob G. Knight provides a practical account of the knowledge, technique, and skills necessary to work with older adults in a therapeutic relationship. This volume considers the essentials of gerontology as well as the nature of therapy in depth, focusing on special content areas and common themes.

Psychotherapy with Older Adults includes a comprehensive discussion of assessment and options for intervention. Numerous case examples illustrate the dynamics of the therapeutic task and issues covered in therapy and stress the human element in working with older adults. A concluding chapter considers ethical questions and the future of psychotherapy with older adults. The author has updated the Third Edition to reflect new research findings and has written two entirely new chapters covering psychotherapy with persons with dementia and psychotherapy with caregivers of frail older adults.

Since its initial publication in 1986, the book has been used as a course text and a professional reference around the world, including translations into French, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese. It is a vital resource for practicing therapists and counselors who work with older adults and is also ideally suited as a text for advanced students in psychology, social work, gerontology, and nursing.

Praise for Previous Editions:

"Bob G. Knight?s largest contribution is his excellent discussion of therapy. The book is clearly written, with a good use of summaries and case examples to clarify the major points. By linking research findings to practice experience, Knight has provided a pragmatic introduction which should be helpful to psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses working with older adults." —JOURNAL OF APPLIED GERONTOLOGY

"I recommend this book to anyone interested in working with the elderly, partly because of the content and partly because the author presents the case for doing psychotherapy with the elderly with realism and enthusiasm." —BEHAVIOR RESEARCH & THERAPY

Psychotherapy with Older Adults includes a comprehensive discussion of assessment and options for intervention. Numerous case examples illustrate the dynamics of the therapeutic task and issues covered in therapy and stress the human element in working with older adults. A concluding chapter considers ethical questions and the future of psychotherapy with older adults. The author has updated the Third Edition to reflect new research findings and has written two entirely new chapters covering psychotherapy with persons with dementia and psychotherapy with caregivers of frail older adults.

Since its initial publication in 1986, the book has been used as a course text and a professional reference around the world, including translations into French, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese. It is a vital resource for practicing therapists and counselors who work with older adults and is also ideally suited as a text for advanced students in psychology, social work, gerontology, and nursing.

Praise for Previous Editions:

"Bob G. Knight?s largest contribution is his excellent discussion of therapy. The book is clearly written, with a good use of summaries and case examples to clarify the major points. By linking research findings to practice experience, Knight has provided a pragmatic introduction which should be helpful to psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses working with older adults." —JOURNAL OF APPLIED GERONTOLOGY

"I recommend this book to anyone interested in working with the elderly, partly because of the content and partly because the author presents the case for doing psychotherapy with the elderly with realism and enthusiasm." —BEHAVIOR RESEARCH & THERAPY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychotherapy with Older Adults by Bob G. Knight in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gerontology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

SAGE Publications, IncYear

2004Print ISBN

9780761923732, 9780761923725eBook ISBN

97814522381801

Gerontology

for Psychotherapists

The Contextual, Cohort-Based, Maturity, Specific-Challenge Model

CASE STUDY

Mrs. G is a 75-year-old woman who has come to see a psychologist on the advice of her granddaughter. The granddaughter has felt that Mrs. G was depressed and that therapy might help because she herself had a good experience with therapy while at the state university. Mrs. G has been widowed 3 years and has never gotten over her grief. The past 2 months have included the anniversary of her husband’s death, her 75th birthday, and the departure of a friend who has moved to another community. She has become more depressed, is losing weight, and complains of not sleeping soundly, as well as not being able to remember things like she used to. She is very unsure about what the therapist can do for her; her granddaughter has only been able to say that talking to the therapist will help. The waiting room reminds her of a doctor’s office, and she thinks that perhaps she will get medication or the same kind of friendly but firm advice that her family physician (who died 10 years ago) used to provide. She knows that therapy has to do with mental health and worries that the psychologist will evaluate her and put her in a psychiatric hospital.

When the psychologist comes to the waiting room, Mrs. G is surprised that the therapist is young. The psychologist looks surprised at Mrs. G’s age and appears uncomfortable. When Mrs. G wavers a little as she stands up from the waiting room couch, the psychologist (Dr. Q) unexpectedly and somewhat awkwardly grabs her to steady her, which annoys Mrs. G and makes her feel more unbalanced for a second. Once in the therapy room, Mrs. G has difficulty understanding Dr. Q, who tends to speak rather quietly and with an accent that marks him as being from out of state. At times, Mrs. G guesses what is being asked and is not sure how the answers are being taken because she cannot see the therapist’s face very well. The room is dimly lit, and Mrs. G has not replaced her glasses in 5 years because of the expense.

After an hour-long visit in which Dr. Q and Mrs. G have each become progressively more nervous, Mrs. G leaves with the strong feeling that the doctor thinks she is demented, and with the advice that “It’s normal to feel depressed at your age.” She worries for the next 3 months about whether she will be able to afford the psychologist’s bill. Although the clinic secretary said that the fee might be covered by her Medicare managed care plan, no one told her what her fee would be if Medicare did not cover it. Mrs. G does not believe her insurance will cover a visit with a psychotherapist. When no bill arrives, she concludes that the doctor saw her as a charity case and feels even more depressed. Her granddaughter urges her to see another therapist, but Mrs. G refuses and secretly feels relieved that she was not sent to the geriatric unit of a local private psychiatric hospital.

Why Did This Happen?

In this example, Mrs. G is unfortunately burdened with most of the problems that older people have in seeking therapy. There are many like Mrs. G, and many more who have only some of these problems and misconceptions. Older people often have had less exposure to and less informal education about psychotherapy and outpatient mental health services than have the younger adults who make up the majority of therapists’ caseloads.

Many of today’s older adults grew up in a time when “mental health” meant long-term stays for psychotic individuals in locked wards in state hospitals far from home. Relatively few of today’s elderly went to college, and the ones who did are less likely to have taken psychology classes. They may be less likely to have known if any friends or family members sought therapy for other than extremely severe mental disorders. For all of these reasons, the elderly are unlikely to have a clear idea of what out-patient therapy is and how it could be of help to them. If the therapist does not play an active role in educating the elderly client early in therapy, the client will fill in the gap with fantasies and with experiences based on visits to physicians or clergy.

Because a relatively small number of therapists are trained to work with the elderly, it is also likely that the client will encounter a therapist who has little experience dealing with an older client. The therapist may be wondering, without knowing how to find out, if the client has Alzheimer’s disease; the therapist may also feel that depression and even suicide are understandable responses to being old. In as much as many elderly are hard of hearing or visually impaired, there are likely to be communication difficulties that will block the building of rapport and may strengthen the therapist’s suspicion that the client is demented and cannot benefit from therapy. In short, what could have developed into a therapeutic relationship that would have helped Mrs. G to conquer her depression and establish a new life as a happier widow failed to develop at all. Mrs. G has the added worry of the therapist’s bill and a sense of being beyond help. With a little added work on the therapist’s part, however, the experience could have been much different and a successful therapy could have been started.

Combating Misconceptions About Older Adults

This book is motivated in large part by my observation that there are a growing number of psychotherapists who are working with elderly clients. This is due in part to the growing number of older adults in the population, in part to the fact that many of those older adults are now from generations that are more open to psychotherapy, and in part to changes in the Medicare reimbursement system that have expanded reimbursement for services to older adults. As most training programs for therapists do not provide much knowledge or experience of older people, therapists must often grope for clues to help them work with and think about older people. The intended aim of this book is to provide a general guide to therapists with older clients, with particular attention to introducing therapists to basic concepts in scientific gerontology and life span developmental psychology and to addressing the ways in which work with older adults may differ, or seem to differ, from work with younger adult clients.

Gerontology is a multidisciplinary field of study to which scholars have traditionally come after completing training in one of the constituent disciplines. However, in the past 30 years or so, increasing numbers of persons have received degrees in gerontology. Constituent disciplines have included biology, medicine, nursing, psychology, social work, and sociology. Historically, services to the elderly were mainly delivered by social workers and nurses, who have been joined in more recent years by planners in the aging network, nursing home administrators, rehabilitation and recreation therapists, paraprofessionals involved in senior centers and nutrition sites, physicians and psychologists.

The complex array of perspectives, persons, and disciplines in gerontology obviously generates a body of knowledge of considerable complexity that cannot be well summarized in a large book, much less in a short chapter. However, there are within the discipline some general perspectives, trends in findings, and key sources of information that can present the therapist with very different concepts of aging and of the elderly than he or she is likely to have gotten from coming of age in our culture. It is these novel ways of thinking about aging that are discussed in this chapter.

Psychotherapy with older adults has been done, discussed, and studied for about eight decades. In general, both the case studies and the controlled research on outcomes have been positive (Knight, Kelly, & Gatz, 1992). For the most part, people who have experience doing psychotherapy with older adults have described it as valuable for clients and rewarding for the therapist, whereas those who have not worked with older adults have argued that the aged cannot benefit from psychotherapy. Since the 1970s, writing about therapy with older adults has increasingly drawn upon scientific gerontology (Knight et al., 1992). Reviews of the literature that evaluate the outcomes of psychological interventions with older adults leave no doubt that psychological work with older adults is effective and roughly equivalent to the effectiveness of psychiatric medication with older adults and to psychological work with younger adults (Gatz et al., 1998; Pinquart & Sörenson, 2001; Scogin & McElreath, 1994).

The early history of gerontology as a discipline was characterized by a split between researchers who were discovering that aging is a more positive experience than society presumably believed and practitioners who were struggling with the problems of selected elderly and who generalized the real problems of frail older adults to all aging persons. The loss-deficit model of aging, which portrays the normative course of later life as a series of losses and the typical response as depression, has been an integral part of the practitioner heritage.

On the other side, life span psychology has brought important conceptual and methodological advances to the study of adult development and aging. Chief among these has been the insistence on using longitudinal methods to study the aging process, as opposed to the inexact but common practice of comparing older adults and younger adults at one point in time and drawing developmental conclusions from the observation of differences between young and old people. The development of sequential designs (e.g., Schaie, 1996) that use aspects of cross-sectional and longitudinal methods has brought greater sophistication to the study of adult development and has called attention to two competing influences that are often confused with aging: cohort differences, which are the ways that successive generational groups differ from one another, and time effects, which can be related to social influences that affect everyone at about the same time or which can be specific to changes in the research study itself.

The Contextual, Cohort-Based, Maturity, Specific-Challenge Model

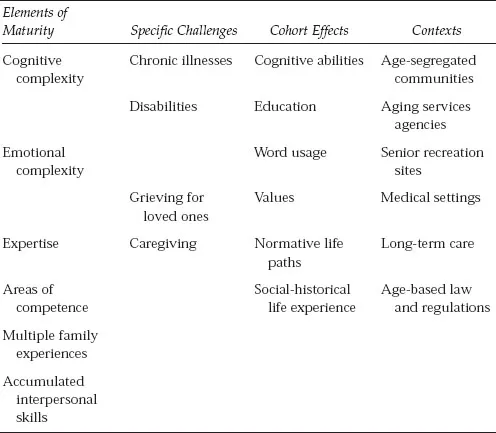

In my own work on psychotherapy with older adults, I have attempted to bridge this gap between science and practice. In part, this attempt was motivated by being puzzled over the discrepancy between the loss-deficit model followed by most practitioners prior to 1980 and the emerging view of life span developmental psychology of the 1970s, which focused on normal aging and was more positive. In recent years, this has led to the proposal of a contextual, cohort-based, maturity, specific-challenge model (CCMSC). In this model, older adults are seen as more mature than younger ones in certain important ways but also are recognized to be facing some of the hardest challenges that life presents to adults, including adjusting to chronic illness and disability as well as frequent grieving for others (see Table 1.1). The special social context of older adults and the fact that they are members of earlier born cohorts raised in different sociocultural circumstances may require adaptations that are not dictated by the developmental processes of aging. In what follows, maturation is discussed first, followed by cohort-differences and contextual factors as important potential sources of difference in working with older adults in therapy. Finally, specific challenges that are not unique to later life, but are more commonly experienced in old age, are introduced.

| Table 1.1 | The Contextual, Cohort-based, Maturity, Specific-Challenge Model |

Maturity

In our culture, it is common to think of the last decades of life as being a time of illness, extreme frailty, and severe declines in memory and other intellectual abilities. In fact, all of these things are possible in late life and are more common in later life than in young adulthood and middle age. However, at present these aspects of later life are not thought to be inevitable consequences of aging but are instead considered the consequences of disease processes, many of which are age related and others of which in fact start at earlier ages but are chronic and so accumulate with age. Those processes which are both chronic and progressive also worsen with age. The combination of these factors makes old age quite challenging for many older people. However, the increased prevalence with aging of chronic health problems does not mean that such problems are synonymous with aging.

We now know, for example, that the most severe forms of cognitive impairment are due to various brain diseases which produce the severe cognitive decline of dementia (see chapter 5). Neuron loss in the brain is not a normal aspect of aging (Ricklefs & Finch, 1995). To identify normal aging with dementia would be roughly analogous to identifying adolescence or young adulthood with schizophrenia. Both disease processes are age related, but neither defines the age period in which it most often occurs.

Biological aging is perhaps best characterized as reflecting a “wear and repair” model (Ricklefs & Finch, 1995). Living a long time inherently means that we are exposed to environmental stresses, toxins, and injuries and also that we have used our bodies a great deal; these constitute the “wear” of wear and repair. Our bodies replace and repair much of this accumulated damage, but the capacity for repair itself seems to wear down to some degree for most of us as time goes by. This declining capacity for repair no doubt underlies much of the association between old age and disease. Nonetheless, there are examples of healthy and successful aging that point to the fact that extreme frailty is not an inevitable part of aging. Death itself is, of course, inevitable, but not always reserved for the very old.

In the remainder of this section, I describe what is known at present about the psychological consequences of aging. Some of these are positive; others do demonstrate decline. In part to counteract the prevailing pessimism about psychological change in later life, the view presented here tends to emphasize positive change.

Microlevel Cognitive Changes With Aging

Slowing. The most pervasive cognitive change with developmental aging is the slowing that occurs in all cognitive tasks where speed is a factor (Botwinick, 1984; Salthouse, 1985). Although reaction time can be speeded up in older adults by practice, exercise, and other interventions, the age difference is seldom completely eliminated. In a thorough review of the literature on this subject, Salthouse (1985) argued convincingly that the probable locus of slowing is in the central nervous system. More recently, the focus of research on cognitive slowing has been perceptual speed (e.g., the speed with which specific letters in an array can be identified). Perceptual speed seems to correlate strongly with higher order intellectual abilities and to explain some of the age-related change in intelligence (Lindenberger, Mayr, & Kliegl, 1993).

Attention. Older adults seem to have reduced attentional resources as compared to younger adults, especially with regard to selective attention: the ability to screen out distracting or irrelevant stimuli or information (e.g., see McDowd & Birren, 1990). Background noise, multiple conversations, and lots of detailed information may overload older adults’ attentional capacity.

Working Memory. Working memory is the cognitive process that actively processes new information and makes active connections between old and new information. The capacity of working memory decreases in later life, quite possibly starting in middle age (see Salthouse, 1991). This may be one reason why older adults report more difficulty in learning new material than younger adults do.

These three basic cognitive processes all show evidence of decline with age. All three point to the need to slow down the presentation of material when working with older adults, both in term of pacing and in terms of the complexity of ideas presented at once. In the next section, changes in learning and memory are presented.

Learning and Memory

Memory is a complex topic in the study of cognitive changes in late life. Recent longitudinal investigations of memory change in older adults over time have generally confirmed decline with age on some memory functions, such as word recall (e.g., Small, Dixon, & Hultsch, 1999; Zelinski & Burnight, 1997). In the same studies, other functions seem to be relatively preserved, such as recognition memory. Zelinski and Burnight (1997) point out that memory change starts earlier than is often thought (observable in middle age) and is slow. They suggest that studies longer than 6 years are usually needed to detect longitudinal memory change. Small et al. (1999) pointed to some aspects of memory functioning that remain stable and others that improve. Older adults do better with structured material, more time to study the material, and with greater environmental support (the use of notes, recognition, and cued recall give better results than free recall; see Smith, 1996, for a review).

In general, what is known about memory now would suggest that even differences between current younger and older adults in memory performance are not large when the material is meaningful and relevant to the older adult and the older adult is motivated to learn (Hultsch & Dixon, 1990; Smith, 1996). In contrast, younger adults do much better than older adults on novel information and learning tasks with no intrinsic meaning (learning lists of words, for example). Of special interest for psychotherapy is the evidence demonstrating that older adults retain emotional material better than neutral material (Carstensen & Turk-Charles, 1994).

Older adults benefit from memory training (Verhagen, Marcoen, & Goossens, 1992), and so their lower memory functioning compared to younger adults is not irreversible. An intriguing problem in this area is that older adults do not spontaneously use mnemonic aids. They can be taught to do so and will improve their memory performance substantially. However, they have to be reminded to use the mnemonic aids at the next session (Botwinick, 1984). If this tendency to need prompting to use newly learned strategies generalizes to the therapeutic context, it wo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1. Gerontology for Psychotherapists: The Contextual, Cohort-Based, Maturity, Specific-Challenge Model

- 2. Adaptations of Psychotherapy for Older Adults

- 3. Building Rapport With the Older Client

- 4. Transference and Countertransference With Older Clients

- 5. Guidelines for Assessment in the Context of the Practice of Psychotherapy

- 6. Grief Work With Older Adults

- 7. Chronic Illness in Later Life

- 8. Psychotherapy and the Person With Dementia

- 9. Psychotherapy With Family Caregivers of Frail Older Adults

- 10. Life Review in Psychotherapy With Older Adults

- 11. Ethical Issues and Concluding Thoughts on Psychotherapy With Older Adults

- References

- Index

- About the Author