![]()

1 | The Political Environment of Cities in the Twenty-first Century |

John P. Pelissero

American cities and urban areas are perhaps the most exciting venues for politics. National elections and political processes, as well as state politics, certainly capture the attention of citizens and the media, but in cities people find the greatest opportunities to directly participate in politics. Here political campaigns are waged door to door, as candidates and groups seek support from residents of their neighborhoods. Communities organize to fight city hall and band together to promote issues ranging from crime prevention to environmental protection, from school reform to tax reform. City residents can talk directly to their mayor or city council member, and they can attend meetings of the school board or public housing authority. Opportunities to run for local offices abound. In cities one will know the bureaucrats who deliver services, from the neighborhood police officer to the solid waste collectors to a health inspector. The “retail” nature of local politics is accessible and engaging. Indeed, face-to-face contact with local politicians, government officials, and bureaucrats gives local politics the comfortable feel of interacting with a neighborhood retailer. It is also filled with opportunities for conflict when alternative values compete with one another for the benefits afforded by urban governments. Cities, their leaders, and institutions must therefore have the capacity to manage conflict and provide the quality of local governance that all of their citizens expect. At the beginning of a new century, the ability of our cities to meet this challenge has evolved, with transformations within the very “system” of urban politics.

When the twentieth century began, cities and their governments did not share fine reputations. Progressive municipal reformers and muckraking journalists condemned the corrupt political bosses and parties that ran cities for their own political and personal gain. City governments were marked by significant operational inefficiency and were often incapable of managing the multiple service functions required to serve growing populations. The municipal reform movement heavily influenced ideas among urban scholars of the early 1900s. They adopted the reformist prescriptions for better urban governance and promoted restructuring of urban governments in an effort to rid them of the overt influence of “politics” (Hays 1964).

By the 1950s it had become clear to urban scholars that “politics” was no less apparent in reformed governments than it was in those that had preceded them (Lineberry and Masotti 1976, 2). Rather than attempting to change the system of politics in cities, many urbanists began to examine the nature of politics in cities and to explain their findings with social science theories. Thus began the era of behavioral studies of cities, in which case studies and survey research were conducted to test theories about urban politics. This research of the 1950s and 1960s was characterized by a debate over who had political power in cities. Although the debate was not convincingly resolved, it forced scholars to consider new issues of access, influence, and representation in cities. This gave way to an interest in understanding the nature of political relationships among citizens, leaders, and institutions in an urban system.

The late 1960s and 1970s were a period of “crisis” in urban America. From civil unrest to political protest, from rising crime rates to declining city revenues, urban areas were forced to confront a host of national problems that took root within the boundaries of central cities and suburbs. The responses of cities to this crisis were many. Some cities changed their structure of government to become more responsive to citizens and develop more efficient ways to deliver services. Political processes were opened to racial and ethnic minorities, who began to be incorporated into political and policymaking systems. New relationships were forged between the national and city governments to enhance the flow of federal money to help cities deal with their problems. Cities also considered new ways to finance their governments, often moving away from general taxation and toward more user fees for local services and programs.

In the 1980s cities began a significant period of redevelopment in response to declining tax bases, as residents and businesses continued to exit central cities for the expanding suburbs, and northern cities lost population and their economic base to growing urban areas of the South and West. This marked the beginning of a phase in which urban economic development became an overriding issue. Cities were forced to become more competitive, vying with one another for population and economic growth. By the 1990s it appeared that many urban areas had succeeded in responding to the changing economic system. In many instances, central cities were experiencing a new period of growth, as they became attractive locales for business development, gentrification of older neighborhoods, and tourism. Many city governments “reinvented” their style of governing and management of services to increase the benefits to residents and visitors.

Cities enter the twenty-first century in a strong position. They have a better capacity to govern. Their economic base is stronger. They are attractive venues for conventions, tourism, and world commerce. Leaders and institutions of city government have become more inclusive and responsive. Urban schools have improved, as a result of the implementation of school governance reforms.

Nonetheless, problems and conflict persist in America’s urban areas. The federal government has curtailed its financial support. State governments mandate new policies for cities but do not provide additional funding to pay for them. Some central cities have not recovered from the economic and social crises that afflicted them in the 1960s. Public schools in central cities are still not as attractive to middle-and working-class families as are those in the suburbs. Despite gains in representation in city and school governing circles, many racial and ethnic minorities still lack full incorporation in urban politics.

What we know about cities, politics, and policy at the start of the twenty-first century is due in large part to the careful research of urban scholars, including those who have contributed to this book. Examining the urban political system from a comparative perspective, in which ideas are tested among many diverse cities and urban areas, scholars have developed our theoretical understanding of cities. The purpose of this book is to place in a contemporary context the major areas of inquiry into urban politics. The field of urban politics demands an anthology that is current and covers the major topics of research, including political participation, power, urban government institutions, intergovernmental politics, and urban and suburban policy. The book uses systems analysis to explore the environment of cities and how it affects patterns of political participation, power distribution, leadership, decision making, and policy implementation. The material is presented from a comparative perspective that emphasizes knowledge derived from empirical works—both case studies and cross-sectional research on U.S. cities. Each chapter has a thorough discussion of key topics, noting how research approaches to these topics have changed over time. These chapters have been developed to tell the reader what we know to be true about cities and to show how the research of the past has informed our knowledge of cities today. The authors synthesize the current state of urban research and highlight the research agenda for the next decade. This collection is the first work in many years that provides comprehensive coverage of urban politics in an anthology that can serve as a primary text or as a supplement to other urban textbooks. We begin with an overview of the system of urban politics.

The Systems Model of Urban Politics

In The Political System, David Easton (1953) began to develop an influential theoretical framework that facilitated an understanding of politics, including urban politics. He applied the open systems models of natural science to the political world, showing that political systems, like natural systems, are open to influences from their environments. The environment is viewed as one that shapes the political process—in which “authoritative decision-makers” respond to inputs, transforming them into political and policy outputs (Easton 1965a, 1965b).

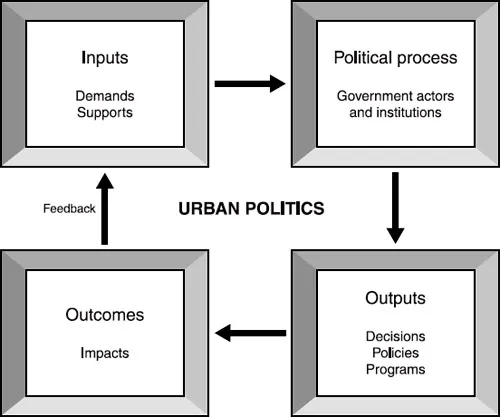

Figure 1-1 presents a model of the urban political system. The open systems framework includes a conceptual scheme of the key components of the model. In broad terms, we theorize that the urban political system is composed of inputs from the political environment that are channeled into the political process. The political process is the essence of deciding the “authoritative allocations of values” (Easton 1965b, 348). The result of the decision makers’ processing of inputs yields outputs. The impact of these concrete decision outputs of political actors produces a set of outcomes that send information back into the environment. The process is best viewed as a continuous stream of feedback to the environment that may result in the alteration and creation of inputs that keep cycling in the system.

Figure 1-1 Urban Political Systems Model

The Environment of Urban Politics: System Inputs

Political inputs are drawn from the environment of cities. Easton’s model describes two varieties of inputs: demands and supports. Actions of individuals and groups produce demands, whereas conditions and resources in a city’s environment provide support for political and policy processes and actions.

Demands

Demands are made by individuals and groups who have a stake in the urban political process. This would include action by individuals who function as demand makers, such as citizens, residents, taxpayers, and visitors. Acting on their own and not viewed as part of an organized movement, individual demand makers may contact government institutions or officials in person or in writing to express their views on public issues.

Demands also come from groups of organized citizens and potential groups that can influence the political process. Interest groups made up of individuals with a common interest or characteristic are active demand makers in the urban context. This may include business-related groups, labor organizations, neighborhood groups, racial and ethnic groups, environmentalists, and taxpayer organizations. Each attempts to influence the political process through information, requests, or mobilization of its membership (Berry, Portney, and Thomson 1993; Galaskiewicz 1981; Rich, Giles, and Stern 2001; Schumaker and Getter 1983).

Political parties and local caucuses represent another type of group that makes demands in the system. Although the influence of political parties waned after the adoption of key municipal reforms (nonpartisan elections and the appointment of city managers) (Erie 1988; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993), party organizations continue to be important demand makers in many large cities (Hawley 1973; Krebs 1998). For example, Chicago has held nonpartisan elections for city council since the 1930s. Nonetheless, the city’s Democratic Party has dominated the political process in all respects, and nearly every city council member over the past twenty-five years has been a Democrat.

In most cities, major political parties are not directly involved in city government politics, but local parties or a caucus may have active roles in the system. Many reformed governments, seeking ways to replace the political parties’ role in recruiting candidates to run for local office, created formal or informal means for local parties and caucuses to assume this responsibility. Some cities, such as Dallas, operated through a Citizens’ Charter Association to recruit city council candidates who would support the system of government and its pro-business values (Elkin 1987). Many cities have formal “slate making” organizations to select and promote a slate of candidates for local offices (Fraga 1988). A complete discussion of the ways in which citizens and groups participate as demand makers in urban politics is provided in chapters 3 and 4.

Urban regimes constitute another variety of demand maker in the urban system. As explained in chapter 5, these governing coalitions include key actors from the environment who cooperate with local officials in the development of public policy. Regimes provide demands to the political process and support local institutions and officials, thereby shaping public decisions. Regimes, sometimes viewed as the governing coalitions of cities, afford a window on the makeup of the power structure, which is a powerful determinant of public policy. Some regimes have pro-business orientations, such as those in Atlanta or Dallas (see Stone and Sanders 1987). Others may have their base of support among interests in neighborhoods and community groups with a progressive political agenda, such as those in Berkeley (Clavel 1986), Chicago in the 1980s (Bennett 1993), or San Francisco (DeLeon 1992). The variations are extensive (see Logan, Whaley, and Crowder 1997) and are reviewed in chapter 5.

A final component of the demand environment is the media. Because of its ability to set the public agenda though its coverage of news, issues, and politics, the media are also a demand maker in the urban setting. Metropolitan television and radio stations use their resources to report and analyze issues of concern to urban residents. Newspapers are key inputs to the political process through both reporting urban news and editorializing on issues in their opinion sections. The growth of newer media, particularly cable systems and the Internet, has caused exponential increases in demands being filtered through the political processes of cities. E-mail and Web sites offer easier ways to communicate demands to local decision makers. As a recent national survey revealed, more cities are developing communications plans to respond to the new demands brought about by technological developments (Norris and Demeter 1999; ICMA 2002b)

Supports

The other types of inputs to the political system are supporting conditions for action. These supports are drawn from the political environment and contain both active and latent components. Active support is elicited from the overt behavior of the populace, such as voting in city elections and paying one’s local taxes. Overt support for the local political system allows local decision makers to act with legitimacy and confidence. In contrast, withholding active support (for example, not voting in city elections or challenging local tax assessments) can undermine the ability of local actors and institutions to carry out government service. It can also erode the stability of the local political system. Active support works in concert with demand makers to stimulate action from the political system.

Latent support for government action is drawn from four major types of environments that exist as subsystems of the local political environment: physical, socioeconomic, political culture, and intergovernmental. These subenvironments contain passive and covert elements of support for the system.

The physical environment of cities includes aspects of the local climate, geography, and the built environment—those structures within the city limits. Each in its own way supports certain kinds of actions by local government. For example, climatic conditions that include extreme temperatures in summer and winter, snow and ice, rain and floods create an environment that supports government action. Cities must be prepared to provide the needy with refuge from extreme temperatures, such as warming or cooling centers. Cities will acquire snow removal equipment, salt to combat ice on roads, and warning sirens for dangerous storm conditions. The actors and institutions of city government undertake these actions because the physical environment supports policy action. The same can be said for geography. Cities must adjust their services and programs to reflect their geographical setting. Hence, bridges are needed over rivers, marine patrols are required for lakes, and recreation policies are developed for forests, beaches, and parkland. Finally, cities must respond to the built environment. This includes public infrastructure such as roads, sidewalks, subways, airports, and sewers. Public buildings, museums, and sanitation plants are built by cities and other local governments to support a local populace and commercial activity. As cities determine the density, height, location, and type of construc...