![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Brain Primer—Major Structures and Their Functions

Education is discovering the brain and that’s about the best news there could be … anyone who does not have a thorough, holistic grasp of the brain’s architecture, purposes, and main ways of operating is as far behind the times as an automobile designer without a full understanding of engines.

—Leslie Hart (1983)

- Have you ever wondered how the brain works?

- Have you ever wondered what the different parts of the brain do?

- Have you ever wondered why some see effort as futile and others see it as imperative?

The brain is a complex organ whose relationship with learning is undeniable. The primary charge of an instructional leader is to increase learning. Analyze the learning organ and begin to understand how we learn. To develop understanding, it is critical to have anchors of information from which to build upon. This chapter will act as that anchor. Because the remaining chapters in the book may assume knowledge of this chapter, it will serve as a foundation for greater comprehension throughout the remainder of the book. This chapter will discuss the major structures and functions of the brain, what the brain looks and feels like, and how those structures differ in their functions. Readers will explore deep inside the brain to discover the mysteries of this miraculous organ.

Does not understanding how the brain works preclude being an effective instructional leader? Probably not, especially for those who have already enjoyed years of success as an instructional leader. The truth is that brain-compatible methods have been used forever, because they work well, and some people instinctively employ these methods naturally. For those who would benefit from a more deliberate, analytical approach, this book codifies these methods, so instead of relying on experience as the only teacher, an instructional leader can enlist the help of science as well.

An unusually fitting analogy for the workings of the human brain was written by Thomas Armstrong in his book, Neurodiversity (2010). Instead of comparing the brain to computers or control towers, which seems to be common, he compares it to a complex ecosystem. In response to comparisons to the brain being like a machine, he writes as follows:

It isn’t characterized by levers and gears, wires and sockets, or even the simple binary codes of computers. It isn’t hardware or software. It’s wetware. And it’s messy …. The body of a neuron, or brain cell, looks like an exotic tropical tree with numerous branches. The electric crackling of neuronal networks mimics heat lightning in a forest. The undulations of neurotransmitters moving between neurons resemble the ocean tides. (pp. 9–10)

Aside from the beautifully descriptive imagery of this writing, I think this analogy serves as a reminder that understanding the brain is something within everyone’s reach. Although it might be complex, it is an integral part of our world and our lives. Some educators I have worked with have expressed the notion that the brain is somehow too complex to understand. They shy away from the topic in an effort to “leave it to the experts.” Some might even argue that understanding how the brain works is not a good use of an educator’s time. I would argue that the instructional leaders who understand how the brain works gain exponential understandings in every role and responsibility embedded in their charge. When I understand how the brain works, I better understand learning, teaching, responses, behaviors, communication, and motivation. I’d say that’s a pretty good bang for the buck (see Figure 1.1).

BRAIN HEMISPHERES

The human brain weighs about 3 pounds, is about the size of a grapefruit, and is composed of two hemispheres. The consistency of a live brain inside the skull is about that of toothpaste, fresh out of a tube (but wouldn’t stick like toothpaste). Taking both hands and making fists, then placing them, touching each other, knuckles to knuckles, will create a decent model of the human brain. Like the two hands have matching elements (two index fingers, two palms, etc.), the brain’s hemispheres also have matching elements. For almost every structure in one hemisphere, a matching structure in its twin exists. The right hemisphere controls the left side of your body, while the left hemisphere controls the right side. Although these hemispheres are similar in structure, there are a few differences in general function. The hemispheres of the brain excel at different kinds of thinking, which provides the benefit of various ways of sensing and perceiving. The right hemisphere tends to excel at nonverbal, spatial tasks; it helps with things like awareness, sociability, intuition, holistic thinking, estimation, intonation of speech, and visual memories, among other things. The left hemisphere excels in language and verbal and logical tasks, including things like writing and speaking, calculating, analyzing, tending to grammar and literal meaning of speech, and thinking linearly. The two hemispheres appear nearly separate (due to a large fissure down the middle of the brain), but they are connected by a band of fibers called the corpus callosum. The corpus callosum is made up of a band of axons, the part of a neuron that is in charge of sending information to other brain cells. Like a bridge of sorts, the corpus callosum is what allows the left hemisphere to communicate with the right hemisphere.

Figure 1.1 A Bird’s Eye View of the Brain’s Two Hemispheres

Although the idea of being “right-brained” or “left-brained” is antiquated, the two hemispheres do specialize in different ways of thinking. This idea might serve as a good reminder for teachers—that the unique brains in their classroom specialize in different ways of thinking too. There are students who need a holistic grasp of the big picture (right hemisphere) before hanging onto the parts, just as there are students whose need for linear, sequential (left hemisphere) instruction trumps other methods (see Figure 1.2).

CORTEX

The covering over the hemispheres looks like a wrinkled blanket. These folds and undulations are called sulci (the grooves) and gyri (the bumps) and the covering is the cortex. The cortex is six layers thick and packed with nerve cells called neurons (a kind of brain cell). These neurons represent the grayish appearance of the cortex and are referred to as gray matter. The cortex is wrinkled because the wrinkles allow for more surface area. If the cortex were removed and smoothed out, it would be about the size of an extra-large pizza. This allowance is needed because our brains actually grow as we learn. This information is news to many, and when it is shared, it can impact students’ views of their intelligence regarding whether it is fixed or malleable.

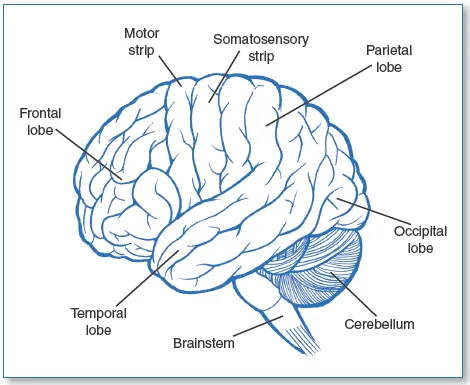

Figure 1.2 Structures of the Brain

CEREBELLUM

In the back of the brain, tucked underneath the cortex, is the cerebellum. Instead of folds and wrinkles, the cerebellum has striated tissue that looks more like muscle. It has more neurons than any other part of the brain, and it supports motor and mental dexterity. It influences our ability to balance and move, as well as different kinds of learning and memory. The cerebellum receives an enormous amount of information from other parts of the brain, and its ability to sort and process information from the cortex is as important as it is impressive. Research regarding the cerebellum playing a larger role in cognition than previously thought might be reason to view activities in school, such as physical education, with careful consideration.

BRAIN STEM

The brain stem is located in the middle of the base of the brain. It is the structure that connects the brain to the spinal cord. Functions of the brain stem include automatic functions, like breathing, the beating of the heart, and blood pressure. The functions of the brain stem are absolutely necessary to sustain life.

LOBES OF THE BRAIN

Now that I have provided a big picture (right hemispheric) of the external structures of the brain, I would like to go into a little more detail. When looking at an image of a human brain, we see certain regions, some more clearly demarcated than others. These different regions of the brain have specialized functions, and they are referred to as lobes. The different structures have different functions, from thinking skills to motor skills, from meaning making to memory retrieving. The part that is active while a person is solving an algebra problem might be different than the part that is working while a person is jogging around a track. This doesn’t mean that only certain sections of the brain work at any one time. Many different areas of the brain work in concert all the time. When thoughts are occurring, a virtual constellation of pathways are involved, with several different regions lending their input. This is why, as will be discussed more later, instruction that includes visual, auditory, and kinesthetic input may be more effective.

There are four main lobes of the brain: the frontal lobes, the temporal lobes, the parietal lobes, and the occipital lobes. The motor strip and somatosensory strip are located between the parietal lobes and the frontal lobes. When we understand the functions of each lobe, we better understand why input that includes different modalities can be so effective—it is co-opting various parts of the brain, which in turn, may create more pathways of thought or recall.

FRONTAL LOBES

The location of the frontal lobes is easy to remember because they are in the front of the head, right behind the forehead. These two lobes represent about a third of the cortex and contain the prefrontal cortex, an area in charge of executive functions. That means the frontal lobes help people think in ways that include setting goals, delaying gratification, recognizing future consequences from current actions, overriding or suppressing inappropriate responses, recalling memories that are not task based, synthesizing information, and making sense of emotions. This area of the brain is the mecca of problem solving, critical thinking, and creativity.

The frontal lobes reach full maturity somewhere in the second decade. This means that many of our students in a K–12 system are not operating with a fully matured brain. This does not mean that children from preschool through high school don’t use their frontal lobes for higher level thinking. What it does mean, however, is that the kinds of executive thinking we can depend on from adults are not always accessible to our students. There are things we can do in schools to act as surrogate frontal lobes for children. For instance, incorporating protocols for goal setting (a function of the prefrontal cortex) in classrooms can act as a scaffold for frontal lobe use. Helping students delay gratification (another function of the prefrontal cortex) by implementing routines in the classroom where students listen to peers without interruption, or take turns, is another way to assist and enlist and guide frontal lobe use.

Because the frontal lobes play such a large role in learning, memory, and higher-level thinking, educators must do what is necessary to protect these precious areas from damage, either physically or psychologically.

PARIETAL LOBES

The parietal lobes are located behind the frontal lobes and in front of the occipital lobes, across the top of the head. The parietal lobes help people integrate sensory information from their environment. Portions of the parietal lobes are involved in visual-spatial processing, known as the “where” and “how” stream. They help people know where they are in space relative to objects that surround them, and they allow us to manipulate our bodies and objects in an effective way. This is what enables people to move through a crowded room without bumping into others along the way or to know approximately how much further one has to walk to get to the coffee shop in sight. Students who display a lack of orienting or integrating information about where their body is in space might, on the surface, simply appear to be clumsy or not “with it” in a classroom. A teacher who understands there is a specific struct...