![]()

Part One

From Contact to Contract

FROM THE FIRST point of contact to the confirmation that an agreement is in place, effective contract management smoothes the way.

Whether you are setting up an informal agreement or a detailed legal contract, it pays to be clear up front about exactly what will be done for and by whom, at what cost, and by when. Building a strong communication base from the start can prevent misunderstandings as well as lengthy and expensive contractual arguments.

Chapter One provides a preliminary screen for exploring an initiative and making a decision about whether to proceed. Chapter Two outlines three types of agreements and describes how to customize them to suit specific processes.

Life being somewhat unpredictable, the steps to an agreement don’t always happen in the order they are presented in these chapters. If, for example, you have a standing offer with an organization or department, the financial aspects of your relationship with this client may already have been negotiated, and the effort discussed in Chapter Two, “Building Agreements That Work,” may not be required.

These first two chapters lay the groundwork for getting facilitated processes off to a good start with focused, fair, and transparent agreements in place.

![]()

Chapter 1

Initial Contact

IT MAY HAPPEN with a phone call, through an advertisement, a request for a proposal, or on the basis of a discussion with a colleague. Regardless of how it occurs, an initial contact to explore possible process consulting work is all about people screening one another, the situation, the expectations, the time, and the cost involved in completing a potential assignment.

During these preliminary discussions, basic information and impressions are exchanged so that all parties can decide whether to move forward and develop an agreement or not. This chapter provides the information needed to support productive exchanges among the various parties during these first encounters.

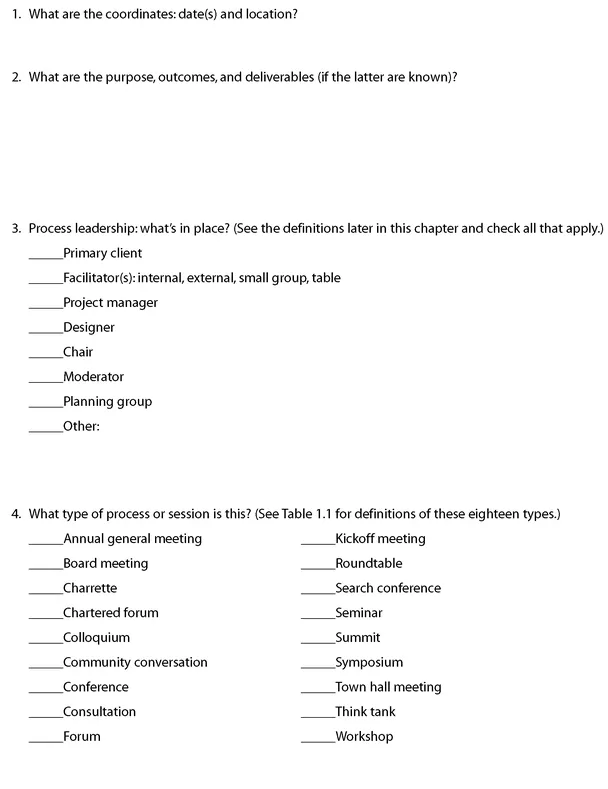

When external process consultants are involved, they are usually looking for information that will help them be successful in bidding on a project or make a decision about whether they can or want to do the work. When internal process consultants are involved, they have often been assigned the work and are looking for information to help them do the best job possible, either on their own or working with colleagues. In situations where the manager is also the process designer and facilitator, the same information needs to be gathered to support the development of a meaningful process. Exhibit 1.1 contains an outline you can use when conducting a preliminary screen. The following section of this chapter offers guidelines and definitions for completing this tool.

When this preliminary screening is completed, all parties should have a sense of the potential scope of the proposed process, the people involved, and whether this would be a good fit for each party. When push comes to shove, it’s a lot like buying a house or starting a new job: you only really understand what’s involved by living in it.

EXHIBIT 1.1: The Preliminary Screen

Completing a Preliminary Screen

Here are practical guidelines for making decisions about the elements often discussed by parties involved in an initial screen as outlined in Exhibit 1.1.

Coordinates: Date(s) and Location

First, determine what session date (or dates) will work with people’s schedules.

• Ask what date would be attractive to the facilitator, to the designer, to the manager, and to potential workshop participants, and why.

• Think about the timing relative to what needs to be done. Does the proposed date allow enough preparation time for the participants and the planning committees?

“Lean on your experience and trust yourself. Your social intelligence—the capacity to engage in satisfying and productive interpersonal relationships—is an important source of information” (Goleman, 2006, p. 82).

• Ask whether other events going on at the proposed time might complement or conflict with this session. How close is the date to national, state or provincial, religious, or school holidays?

Also determine whether the client has identified a location, and if so, explore the possible implications of this location. It’s also important to find out whether some steps will be done virtually.

Purpose, Objectives, and Deliverables

Consider at least these three questions about the purpose, objectives, and deliverables:

• Are they clear and specific, or is the client expecting that they will be clarified during the early part of the session?

• Can you anticipate the most obvious issues and questions that will be involved in managing the session with respect to participants, speakers, logistics, invitations, and essential documents (the elements discussed in Part Three)?

• If the deliverables have been defined, what does your experience tell you about the workload involved in managing a session with these deliverables?

Process Leadership

How a process is led has implications for how it is managed.

Process leadership comes in many shapes and sizes: it may include a client, a process consultant (facilitator and designer), a workshop manager, and two additional staff members to do logistics; it may involve just the client and a facilitator who are responsible for the entire session; or it may be just one person doing everything. Much depends on the size and complexity of the process.

The preliminary screen helps determine what decisions have been made or need to be made about the leadership functions in a process, as itemized below.

The primary client owns the challenge being addressed through a process. This person is usually the individual sponsoring the session and has decision-making authority for what happens before, during, and after a session (Strachan and Tomlinson, 2008, p. 49).

Given the considerable range of situations in which sessions happen, the primary client may be a committee chair, the president or chief executive officer of an organization, the senior manager of a department, the volunteer leader of a community group, or the members of a collaborative or network. Sometimes all the key roles for a process are carried by a single person: in this situation the primary client is also the designer, facilitator, manager, and sponsor for a session.

Be prepared to ask specific questions about the challenges that this process will be addressing. These questions might explore the relationship between the primary client and other clients, who your main contact person is, the relative urgency of the situation, and the nature of participants’ needs and expectations.

One classic question is whether a session should be led by a process consultant, a facilitator, a chair, or a moderator, or someone who combines these functions. For example, an internal client may be thinking that a process consultant is required to design and facilitate a symposium. At the same time, an experienced facilitator might recognize that because symposiums typically have a large number of speakers and offer no time for small-group discussions, a credible chairperson is what is required. Has this decision been made, or are people still discussing what type of leadership needs to be in place given the session purpose, deliverables, and type?

Regardless of how large or small a session is, having a planning or advisory group of two or more people provides a range of perspectives on what to do when and why. Planning group members are also brought on board to build capacity for implementation.

Process Leadership Definitions

• Chair or chairperson: an appointed or elected person with positional authority.

• Moderator: a nonpartisan person who presides over a meeting.

• Process consultant: a person who designs and facilitates processes and also frequently manages them.

• Facilitator: a person who attends to group process. Many people do facilitation as a regular part of their work and yet don’t think of themselves as professional facilitators; they are included in this definition.

Source: Adapted from Strachan and Tomlinson, 2008, p. 49.

Timely liaison knits together people fulfilling these leadership functions with a range of others, such as an organization’s support staff, on-site employees, travel agents, audiovisual technicians, and conference and maintenance personnel. The devil is certainly in the details.

Eighteen Types of Processes

Clarify up front what type of process is being considered. Names of processes can be confusing as there is no single accepted taxonomy for process types. In the past, for example, the term seminar described a series of presentations followed by a brief opportunity for questions and answers. Today a seminar may include both presentations and small learning groups, and participants may experience both activities either in person or virtually.

Some organizations develop their own names for processes that are combinations of the eighteen types listed in Table 1.1. They may use terms such as roundtable seminar or consultation workshop. However, because different types of processes require different types of agreements, it’s important to have everyone on the same page with respect to what is going to happen.

Most processes are held face to face or virtually, or both at the same time; some are conducted solely through on-line exc...