![]()

Chapter 1

Principles of Gerontological Nursing

Debbie Tolson, Joanne Booth and Irene Schofield

Box 1.1 What matters to me: older person

‘A good nurse to me is someone who knows what they are doing and can do it in a way that shows they care, care about me that is. They should speak to me with respect and not simplify information because I am eighty years old. I will ask when I don’t understand.’ (Ronald Newman, 81)

Introduction

Improvements in health and social care have contributed to demographic ageing around the world. This means that nurses who work with adults will increasingly be working with older people (people over retirement age, most often aged 60 years or more). The fastest growing group of the older population is the oldest old, i.e. those who are 80 years old or more. Globally in 2000, the oldest old numbered 70 million and their numbers are projected to increase to more than five times that over the next 50 years (Huber 2005). Adding years to life is a great achievement, particularly when this is accompanied by a good level of health and well being. For many people, however, longevity brings with it an array of challenges, some age related, others condition specific which impact on their lives and those close to them. Increased susceptibility to health problems and the cumulative effect of relatively minor problems coupled with a decreased recovery capacity explains the high demands for healthcare by this group. In addition to changes in states of physical and mental health, social determinants of health such as poverty and social isolation can compound an individual’s problems. The susceptibility of older people to declining health and the global increase in numbers of people living into late old age make compelling reasons to mobilise nursing efforts and for us all to prioritise investment in the development of gerontological practices.

Nurses are uniquely positioned to promote health in later life and to influence care outcomes and experiences for older people and their families. To do this effectively nurses need to draw on the best available evidence and adopt approaches to practice informed by health and medical sciences. Practice will also be influenced by conceptual and cultural understandings and reflect what is possible in the particular nursing situation. This book does not set out to be a definitive practice textbook per se – our intention is to explore the connections between practice, the value base of practice, emergent theory and the continually evolving evidence base which collectively informs how nurses can and do work with older people.

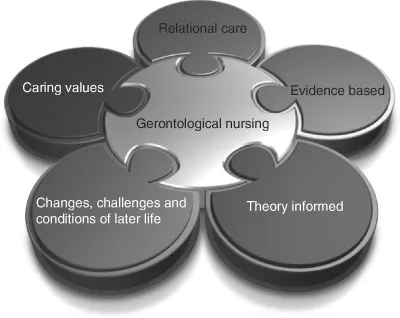

Figure 1.1 Essential connections for gerontological nursing practice.

This foundational chapter will orientate readers to three fundamentally important and related issues which shape contemporary thinking about evidence informed nursing with older people:

(1) the meaning of gerontological nursing and its relationship to the evidence base;

(2) the importance of shaping evidence implementation through a culturally appropriate value base;

(3) the evidence informed management of common geriatric syndromes and health conditions.

Taking this unified view allows individual nurses to make essential connections to inform practice (Figure 1.1).

The introductory discussion is pivotal to understanding the contribution that nurses can and do make to the health and well being of older people. Importantly, we will introduce current debates and emergent ideas about the constituents of nursing practice at its best. The core premise is that nursing at its best occurs when practitioners make connections between the value base, evidence, underlying theory and gerontological practice know-how in the unique moment of care.

Meaning and scope of gerontological nursing

Over recent decades it is possible to trace debates in the literature as to whether nursing older people is a specialism or a component of general adult nursing. Kagan (2009) is critical of this preoccupation, contending that to progress we must focus on the promotion of gerontological principles when nursing people who for reasons of chronological age, illness, injury or genetic disposition manifest needs associated with later life. The Nursing and Midwifery Council of the UK now recognises that nursing older people is a specialism that requires highly skilled nurses who can respond to the complexity of health and social care needs of older people (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2009, p. 6). In addition to recognising the prerequisite skills that practitioners require to nurse older people, McCormack and Ford argued a decade ago that it is essential for nurses to be able to describe the contribution they make to older people’s health and healthcare. If they fail to do so then it is likely that the trend, in some countries, to replace registered nurses with cheaper vocationally qualified support workers will continue (McCormack & Ford 1999).

We take the view that nurses who become expert in working with older people draw on knowledge from applied gerontology, geriatric medicine and generic nursing skills alongside knowledge of the older person, their family and life circumstances.

By describing nurses whose practice is guided by an explicit value base and informed by clinical and applied gerontological knowledge as ‘gerontological’ nurses, a distinction can be made between nurses with expertise, and those with a more general understanding of adult nursing. We believe this distinction is an important one to make as it signals the need for preparation specific to understanding clinical and psychosocial aspects coupled with an appreciation of the aspirations and felt needs of older people. We also concur with Kagan (2009) that all adult nurses should be equipped to apply gerontological principles within their practice.

Approaches to preparing nurses to work with older people vary and are influenced by views about underlying competencies and essential skills sets. Such views inevitably change with development of knowledge and theory and are reflective of national healthcare policies, priorities and service configurations. In the UK for example, recent health policies have promoted respectful and dignified care. These affective dimensions and the relationships within care are reflected in gerontological nursing competencies set out by the national agency for healthcare education in Scotland (NHS Education Scotland 2003). American and European alliances, whilst acknowledging the importance of these dimensions, highlight more clinically orientated perspectives including the differentiation of normal ageing from illness and disease processes, and assessment for syndromes and constellations of symptoms that may be manifestations of other underlying health problems (American Association of Colleges of Nursing 2004; Milisen et al. 2004). Such regional differences reflect local interpretations of nursing roles and functions in relation to older people rather than genuine differences in the underlying knowledge and skills sets which inform practice. In reality nurses need knowledge derived from clinical subjects and social sciences including the arts and humanities, so they can understand both what to do in a technical clinical sense and to convey their caring in ways that are safe and compassionate. There is an emerging consensus in the international literature that the scope of nursing older people embraces:

- health promoting aspects that enable people to optimise health, well-being and independence in later life;

- curative and rehabilitative dimensions that focus on functional or psychological recovery from illness or injury;

- facilitating self-care and enabling effective management of long-term conditions;

- providing care for those who become frail or with limited and/or declining self-care capacity;

- palliative and end-of-life care.

An important consideration for all countries is the attention afforded by pre-registration nursing courses in terms of preparing nurses to meet the varied and complex needs of an ageing population. Given the broad scope of gerontological nursing, working with older people offers ample opportunities for registered nurses to specialise in selective aspects of later life care. A challenge for the profession is to steer a transformative path to ensure a positive future for nursing older people and move away from negative legacies associated with ageist service mindsets and a general lack of investment in this area of healthcare (Hayes & Webster 2008).

We suggest that reframing thinking around the concept of gerontological practice contributes in several ways to the development of a positive mindset, which could facilitate progress (Kelly et al. 2005). Gerontological practice is a multi-professional and multi-agency endeavour, and although our discussions focus on nursing, it is with an appreciation that the clinical, theoretical, conceptual and ethical roots of much of our practice are shared and collaboratively developed with other health and social care disciplines.

The definition of this area of nursing presented in Box 1.2 reflects the previously listed scope of gerontological nursing. The definition was generated inductively through a social participatory programme of research undertaken over a 6-year period within Scotland (Kelly et al. 2005). The definition was formulated collaboratively with nurses from across Scotland working in a spectrum of specialist settings with older people, including acute hospital wards, rehabilitation units, long stay facilities, care homes, community and primary care (Tolson et al. 2006). Hence it has applicability across UK care environments and potentially beyond. An additional feature of the definition is that older people were also involved in its preparation. Critique and feedback on the original definition agreed in 2001 was invited from 11 gerontological nursing communities of practice over a period of 5 years (www.geronurse.com; Tolson et al. 2007, 2008) and it is noteworthy that the only requested amendment was made in 2004 when the concept of person-centred care was substituted with relationship-centred approaches. This suggests that the definition captures the contemporary meaning of gerontological nursing for practitioners and older people within Scotland and we also believe that it is in tune with international descriptions. Participants who collaborated in the development of this definition recognised that to realise their vision, a nurse would require in-depth, evidence informed gerontological nursing knowledge, skills and experience together with commitment to an explicit value base shared with members of their local multidisciplinary team. For some this definition represented an important stage in demonstrating professional identity, improving status and conveying their growing confidence in a new era of nursing with older people.

Box 1.2 Defining gerontological nursing

Gerontological nursing contributes to and often leads the interdisciplinary and multi-agency care of older people. It may be practised in a variety of settings although it is most likely to be developed within services dedicated to the care of older people.

It is a relationship-centred approach that promotes healthy ageing and the achievement of well-being in the older person and their family carers, enabling them to adapt to the older person’s health and life changes and to face ongoing life challenges. See www.geronurse.com

Our definition (Box 1.2) highlights that gerontological nursing is relevant within any setting where older people receive healthcare and that it is not the exclusive domain of units dedicated to the care of older people. Importantly, the definition acknowledges the potential leading role played by gerontological nurses working as part of a multi-professional care team. Interestingly, most nurses who practise gerontological nursing do not use this term in their job title, preferring descriptions which are more meaningful to the public.

That said, an agreed definition and clarity about the principles of gerontological nursing are useful in that they enable nurses to describe their contribution or potential contribution to the healthcare of older people. Furthermore, it is an important step towards understanding the core gerontological knowledge and skills that underpin safe practice. This in turn should determine how we prepare practitioners to work with older people, either as a component of their general adult nursing role or as specialists with increased knowledge. Now that we have defined the area of practice and delineated the range of knowledge necessary to equip practitioners we can begin to examine the adequacy of our practice know-how, the underlying evidence base. Following this we can make theoretical connections to develop and advance practice. In this way we can demonstrate aspects of practice that are informed by evidence to be of demonstrable or perceived benefit to older people and reconsider aspects that are of questionable benefit. We will consider the issue of evidence, information use and appraisal within practice more closely in Chapter 2.

For now let it suffice to say that it is only by drawing on a credible inclusive evidence base that we can begin to understand how to optimise outcomes for older people and realise the potential of gerontological nursing. Griffiths (2008) suggests that by focusing on outcome indicators with older people, nurses have an opportunity to move beyond traditional approaches of identifying the problems and needs of older people. Rather, Griffiths (ibid.) argues that we should begin by identifying the desired outcomes of healthcare with the person and from this position recognise the nursing contribution t...