- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Kids and teachers can build their own science projects based on exhibits from San Francisco's premiere science museum

This revised and updated edition offers instructions for building junior versions, or "snacks, " of the famed Exploratorium's exhibits. The snacks, designed by science teachers, can be used as demonstrations, labs, or as student science projects and all 100 projects are easy to build from common materials. The Exploratorium, a renowned hands-on science museum founded by physicist and educator Frank Oppenheimer, is noted for its interactive exhibits that richly illustrate scientific concepts and stimulate learning.

- Offers a step-by-step guide for building dynamic science projects and exhibits

- Includes tips for creating projects made from easy-to-assembly items

- Thoroughly revised and updated, including new "snacks, " images, and references

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Exploratorium Science Snackbook by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teaching Science & Technology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE CHESHIRE CAT AND OTHER EYE-POPPING EXPLORATIONS OF HOW WE SEE THE WORLD

How do you see the world around you? You open your eyes and there it is: your room, your desk, the pictures on the walls, the trees outside your window.

When you take a look at the world, here’s what’s happening: Light is bouncing off the pictures, the trees, and all the things out there in the world. Some of that light gets into your eye. This light shines through the cornea, the tough, clear covering over the front of your eye, and then through the pupil, the dark hole in the center of your iris, the colored part of your eye. Your eye’s lens focuses this light to make an image on your retina, a thin layer of light-sensitive cells that lines the back of your eyeball. The light-sensitive cells of the retina signal the brain, and the brain creates a mental image. Finally, you see the world “out there.”

People have compared the eye to a film-loaded camera—and for good reason. Both your eye and a camera have adjustable openings that let in light: the pupil of your eye and the aperture of a camera. Both focus the light to make an image on a light-sensitive screen: the retina of your eye and the film of a camera.

But unlike a camera, your eye doesn’t just passively record the image it receives. Working together, your eyes and brain decide what to see and how to see it. They fill in gaps in your visual field, taking limited information and creating a complete picture. They interpret the limited and distorted images that they receive and try to make sense of the world out there, often using past experience as a guide. They constantly filter out and ignore extraneous information.

You don’t believe it? Then close one eye and take a look at the tip of your nose. You can see it clearly if you think about it. It’s always in your view. Open both eyes and you can still see it, a shadowy protuberance in the center of your visual field. If you think about the tip of your nose, you can see it—but most of the time you don’t notice it (even though it’s as plain as the nose on your face).

The experiments in this section will show you some other sights you usually don’t notice. Some experiments, such as Blind Spot, Pupil, and Afterimage, will help you understand more about how your eye works—its abilities and limitations. Others, like Vanna and Far-Out Corners, show how prior experience often influences perception: how what you “see” may not be what you “get.” Still others, like Persistence of Vision and Jacques Cousteau in Seashells, demonstrate that your eyes and brain work together to make a picture of the world. Finally, some show how your eyes and brain can make mistakes in their interpretation of the world—mistakes that create optical illusions, deceptive pictures that fool your eyes.

Taken together, the experiments in this section let you explore visual perception, a fascinating interdisciplinary topic where biology and psychology overlap.

AFTERIMAGE

A flash of light prints a lingering image in your eye.

Materials

• Opaque black tape (such as electrical tape)

• White paper

• A flashlight

Introduction

After looking at something bright, such as a lamp or a camera’s flash, you may continue to see an image of that object when you look away. This lingering visual impression is called an afterimage.

Assembly

(15 minutes or less)

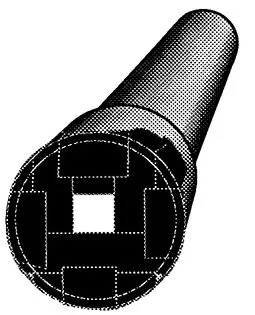

1. Tape a piece of white paper over a flashlight lens.

2. Cover all but the center of the white paper with strips of opaque tape.

3. In the center of the paper, leave an area uncovered where the light can shine through the paper. This area should be a square, a triangle, or some other simple, recognizable shape.

To Do and Notice

(15 minutes or more)

In a darkened room, turn on the flashlight, hold it at arm’s length, and shine it into your eyes. Stare at one point of the brightly lit shape for about 30 seconds. Then stare at a blank wall and blink a few times. Notice the shape and color of the image you see.

Try again—first focusing on the palm of your hand and then focusing on a wall some distance from you. Compare the size of the image you see in your hand to the image you see on the wall.

Close your left eye and stare at the bright image with your right eye. Then close your right eye and look at the wall with your left eye. You will not see an afterimage.

Etcetera

For up to 30 minutes after you walk into a dark room, your eyes are adapting. At the end of this time, your eyes may be up to 10,000 times more sensitive to light than they were when you entered the room. We call this improved ability to see “night vision.” It’s caused by the chemical rhodopsin in the rods of your retina. Rhodopsin, popularly called visual purple, is a light-sensitive chemical composed of retinal (a derivative of vitamin A) and the protein opsin.

You can use the increased presence of rhodopsin to take “afterimage photographs” of the world. Here’s how:

Cover your eyes to allow them to adapt to the dark. Be careful that you do not press on your eyeballs. It will take at least 10 minutes to store up enough visual purple to take a “snapshot.” When enough time has elapsed, uncover your eyes. Open your eyes and look at a well-lit scene for half a second (just long enough to focus on the scene), then close and cover your eyes again. You should see a detailed picture of the scene in purple and black. After a while, the image will reverse to black and purple. You can take several “snapshots” after each 10-minute adaptation period.

What’s Going On?

You see because light enters your eyes and produces chemical changes in the retina, the light-sensitive lining at the back of your eye. Prolonged stimulation by a bright image (here, the light source) desensitizes part of the retina. When you look at the blank wall, light reflecting from the wall shines onto your retina. The area of the retina that was desensitized by the bright image does not respond as well to this new light input as the rest of the retina. Instead, this area appears as a negative afterimage, a dark area that matches the original shape. The afterimage may remain for...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Welcome to the 2009 Edition of the Exploratorium Science Snackbook

- Introduction

- What’s in a Snack?

- Icon Key

- Tips and Tales—By Teachers, for Teachers

- PART ONE - THE CHESHIRE CAT AND OTHER EYE-POPPING EXPLORATIONS OF HOW WE SEE ...

- PART TWO - THE COOL HOT ROD AND OTHER ELECTRIFYING EXPLORATIONS OF ENERGY AND MATTER

- PART THREE - THE MAGIC WAND AND OTHER BRIGHT EXPLORATIONS OF LIGHT AND COLOR

- PART FOUR - THE SPINNING BLACKBOARD AND OTHER DYNAMIC EXPLORATIONS OF FORCE AND MOTION

- PART FIVE - THE WIRE-HANGER CONCERTO AND OTHER EAR-SPLITTING EXPLORATIONS OF ...

- About the Exploratorium and the Exploratorium Teacher Institute

- Contributors

- National Science Education Standards

- Concept Index

- References and Resources

- Content Index