eBook - ePub

Splendors and Miseries of the Brain

Love, Creativity, and the Quest for Human Happiness

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Splendors and Miseries of the Brain examines the elegant and efficient machinery of the brain, showing that by studying music, art, literature, and love, we can reach important conclusions about how the brain functions.

- discusses creativity and the search for perfection in the brain

- examines the power of the unfinished and why it has such a powerful hold on the imagination

- discusses Platonic concepts in light of the brain

- shows that aesthetic theories are best understood in terms of the brain

- discusses the inherited concept of unity-in-love using evidence derived from the world literature of love

- addresses the role of the synthetic concept in the brain (the synthesis of many experiences) in relation to art, using examples taken from the work of Michelangelo, Cézanne, Balzac, Dante, and others

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Splendors and Miseries of the Brain by Semir Zeki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Abstraction and the Brain

Chapter 1

Abstraction

There are many functions that we can assign to the brain, and more specifically to the cerebral cortex, that thin sheet containing billions of cells that envelopes the cerebral hemispheres. Among these one can enumerate seeing, hearing, sensing, the production of movement and of articulate language and much else besides. But do these diverse functions have anything in common? Is there some overall function of which these particular functions are specific instances? The question is not only interesting but also imposes itself, strangely, because of a simple anatomical fact, namely the general uniform anatomical architecture of the cerebral cortex.

A section taken through the cerebral cortex and stained by some anatomical method that shows how its cells are distributed will reveal two interesting features. One is that its billions of cells can be classified into relatively few types, perhaps even into only two basic ones. One of these is pyramidal in shape and the other is star shaped (Figure 1.1). An expert anatomist may well disagree with such a simplistic classification. He may point out with justice that pyramidal cells come in different sizes, that they can be sub-classified into small, medium, and large, or even “gigantic.” He may want to sub-classify the star-shaped cells into those whose processes contain little spines and those that do not. More enthusiastic anatomists will find further subdivisions, indicative of important functional differences and requiring different anatomical techniques to show them. In general, however, examining the brain with a technique designed to reveal the anatomy of the cells in the cerebral cortex will reveal a remarkably uniform picture, one in which cells can be, and have been, classified most easily into these two types.

Figure 1.1. Distribution of the two main types of cells - pyramidal (P) and stellate (S) - in the layers of the cerebral cortex. (From Ranson SW, Clark SL (1959). The Anatomy of the Nervous System, 10th edn, first published 1920. W.B Saunders Company, Philadelphia and London.)

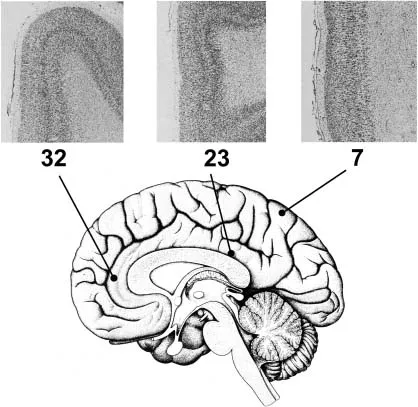

The other striking feature of the cerebral cortex is the uniformity with which these cells are distributed within it (Figure 1.2). Throughout, they are stacked upon one another in layers. It is traditional to subdivide the cortex into six layers, with layer 4 containing the star-shaped cells and the layers above and below containing the pyramidal cells. So uniform and ubiquitous is this arrangement that it takes an expert with many years’ experience to tell differences in anatomical architecture between one cortical region and another. Even if he can, other experts are certain to dispute it. There are, to be sure, some cortical zones that have an obvious difference, visible at a glance. The primary visual cortex, area V1, has an especially rich layering pattern that makes it easily differentiable from adjoining cortex. The primary motor cortex also has a distinctive architecture, in that it lacks the star-shaped cells. Even these do not constitute radical departures from the common plan but are more in the nature of variations on a theme. Much more impressive is the general architectural uniformity of the cortex. This is surprising, given that different cortical fields and areas, which share the same anatomical architecture, differ so profoundly in function. Apart from the fact that they are both senses, there is a huge difference between hearing and general sensibility (touch, pressure, etc.) and, not surprisingly, these two faculties are assigned different cortical areas. Yet it would be hard to tell the differences in anatomical architecture between the two cortical areas subserving these different functions, except perhaps for the specialist. We now know that there are many different visual areas in the cortex surrounding the primary visual cortex, and that these different visual areas share the same architecture although they have different functions, some being specialized for color, others for visual motion, others for the perception of faces, and so on. This diversity of functions exhibited by cortical areas that have a common architectural plan is surprising. It runs counter to an anatomical law, that organs with different functions have different structures and architectures. If one were to study in a similar way (i.e. by staining the cells in anatomical sections) other organs of the body that are known to have different functions, such as the heart, kidney and liver, one would find huge differences that are visible at a glance even to a lay person, and thus do not require an expert for their detection.

Figure 1.2. Structural uniformity of the cerebral cortex. The basic architecture of the cortex is very similar in different parts of the brain. Three sections through different parts of the cortex are shown, from areas 7, 23, and 32 according to the classification given by the German anatomist Korbinian Brodmann. The sections are stained by an anatomical method to show how the cells are distributed. (Sections taken from Paxinos G (ed.) (1990). The Human Nervous System, Academic Press, New York, with permission.)

This is an interesting fact that not only requires an explanation but may also give us some useful hints in thinking about what the cortex does. In general, it may be said that cells in different cortical areas derive their differences largely from the fact that they have different anatomical connections, that is, different inputs and outputs, although other factors also influence their specializations. The auditory cortex connects with the cochlea of the ear and the visual cortex with the retina of the eye. Different visual areas outside the primary visual cortex have specific connections reflecting their functional specialization. Yet these different anatomical inputs act upon areas that share the same anatomical architecture. This essential uniformity has sometimes tempted students of the brain to ask whether there is any function, perhaps even a single fundamental function, that the cerebral cortex performs repetitively everywhere, regardless of the specialization of the area, a sort of supra-modal operation. To date, no satisfactory answer has been obtained to that question. Even so, the value of the uniform anatomical picture of the cerebral cortex lies not so much in providing an explanation but in initiating an enquiry into what, if any, uniform function can be ascribed to every part of the cerebral cortex. It is a spur to thinking about the general function of the cerebral cortex.

Abstraction in the Cerebral Cortex

A useful way to begin this enquiry is to study the responses of single cells in different cortical areas and learn what common property they have. Such an approach may seem odd, given that physiologists have tended to emphasize how specific in their responses cells in different cortical areas are and therefore how much the responses of cells in one cortical area differ from those in another: cells in the auditory cortex will respond to auditory stimuli, those in visual cortex to visual stimuli, and so on. Indeed, the description of how cells in different areas of the cerebral cortex differ in their responses is one of the great triumphs of physiology. But in thus emphasizing the specificity in the responses of cells within different cortical areas, physiologists have overlooked another critical feature, namely the capacity of these specific cells - whether auditory, visual, somato-sensory or otherwise - to abstract. In fact, the capacity to abstract seems to accompany, and to be a corollary of, every specificity. It may therefore be said to be a common property shared by a very great majority of cells and therefore areas of the cerebral cortex, of which these cells are the constituents.

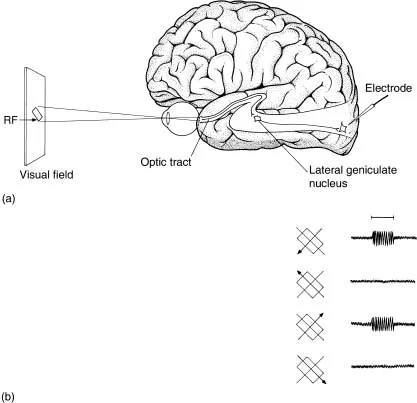

What I mean by abstraction is the emphasis on the general property at the expense of the particular. Its meaning in terms of single cell responses in the cortex becomes clearer when one considers actual examples. Let us take orientation selectivity1, a property of many cells in the primary visual cortex and some other areas of the visual brain (Figure 1.3).2 These are visual cells that respond to lines of certain orientation, and respond less well to other orientations and not at all to lines oriented orthogonally to their preferred orientation. To that extent, these cells are highly specific for the kind of visual stimulus to which they will respond, a feature that has been often enough emphasized in the physiological literature. What has received far less emphasis, if any at all, is that these cells also abstract the property of orientation selectivity in that they are not concerned with what it is that is of the right orientation for them. An orientation-selective cell that responds to vertically oriented lines only will respond to a pencil if held vertically, or to a ruler, or to a white/black boundary. It will respond as well to a vertically oriented green line against a red background, or vice versa. In other words, its only concern is that the visual stimulus should be vertically oriented, without being concerned with what is vertically oriented. The cell has quite simply abstracted the property of verticality, without being concerned about the particulars.

Figure 1.3. Response of an orientation selective cell, studied by inserting an electrode into the visual cortex (a) and by flashing light bars of different orientation into its receptive field (RF), that is the part of the field of view which, when stimulated, results in an electrical discharge (response). (b) shows that the cell is orientation selective, responding to an obliquely oriented line flashed into its receptive field and moved in two opposite directions, while being unresponsive to the orthogonal orientation. (From Zeki, S. (1993), A Vision of the Brain, Blackwell Science, Oxford.)

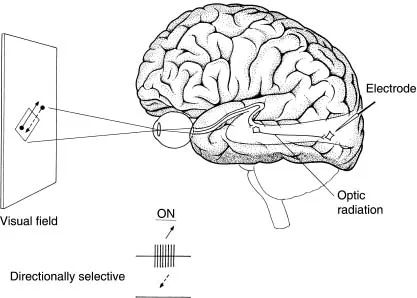

Another example is provided by the cells of another visual area, area V5, which is specialized for visual motion (Figure 1.4).3 The great majority of cells in this area are directionally selective, in that they respond to motion of a visual stimulus in one direction and not in the opposite, null, direction. But they will respond to a black spot against a white background, or vice versa; they will also respond to a green spot against a red background, or vice versa; and so on. Although these cells usually respond best to spots that are moving in a specific direction, they are capable of responding to almost any form, provided it moves in their preferred direction. In other words, they abstract for the direction of motion without being especially concerned with what is moving in their preferred direction.

Figure 1.4. The responses of a directionally selective cell in area V5. The cell responds to motion in one direction but not in the opposite, null, direction. Such cells commonly prefer small spots to oriented bars of light. (From Zeki S (1993). A Vision of the Brain, Blackwell Science, Oxford.)

These examples of abstraction, observed at the physiological level, are not restricted to areas of the visual brain. A cell in the somato-sensory cortex that is specific for detecting pressure will respond to any stimulus as long as it exerts pressure in the appropriate place on the body surface. A cell that responds to high temperatures is not concerned with what it is that produces the high temperature, but only that there is a high temperature. Similar examples may be given for the auditory cortex.

Nor are the examples limited to sensory areas of the brain. Other examples can be given concerning cognitive properties, but the evidence here is derived from a somewhat different experimental approach. Rather than detecting changes in the responses of individual cells to stimulation, such experiments measure changes in the activity of an entire brain area when humans undertake a specific task such as looking at paintings of a particular type, say portrait paintings, or judging which one of two stimuli has a greater magnitude. The areas of the cerebral cortex that are specifically activated can be inferred from detecting the change in blood flow through them, using modern techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). When cells in a given area of the brain are particularly active, their metabolic requirement increases and hence more blood is channeled to the area. These changes in blood flow are thus a good guide to increases in the responses of cells in these areas. In such experiments, if subjects are asked to detect which of two stimuli has the greater value - for example which is brighter, which is larger, which contains the higher number, which is the higher note - the result is always the same and involves the activation of a specific brain area located in the parietal cortex.4 This suggests that the same brain area is specifically engaged in evaluating magnitude, irrespective of the modality in which the magnitude is presented. Equally, another area but this time located in the frontal lobe detects patterns that change irregularly and unpredictably with time, without being concerned with the precise stimulus that so varies, that is, whether the irregular pattern is that of letters, numbers, or colors.5 Although the identity and general physiology of these areas has not been worked out with anything like the precision that the visual areas have, the general direction in which they point is the same - that areas of the brain are capable of abstracting. In these instances, the relevant brain areas are not especially concerned with a higher value of some specific modality or a particular temporal irregularity but only with higher values or irregular patterns in general.

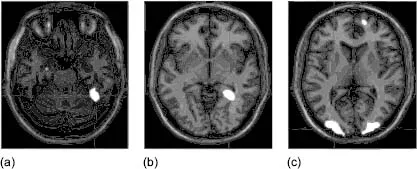

Another example concerns works of art. When subjects view paintings of a particular category, for example portraits, the increase in activity within the visual brain is specific to those visual areas that have been shown to be specifically engaged when humans view faces in general (Figure 1.5).6 But activity is also elicited with any portrait, not a specific portrait. A different (and adjacent) visual area of the brain becomes active when they view another category of painting, for example landscapes, an area apparently specialized for registering places.7 Once again, the viewing of any landscape activates the area. At this level of observation, it may be said that these areas abstract in the sense that they are not specific for any given example of the visual world that they are specialized in but for all examples of that category.

Figure 1.5. Brain activity during viewing of different categories of paintings. Areas in white show regions of maximum activity when subjects view (a) portraits, (b) landscapes and (c) still lifes. (Figure adapted from Kawabata H, Zeki S (2004). Neural correlates of beauty. J Neurophysiol 91: 1699-1705.)

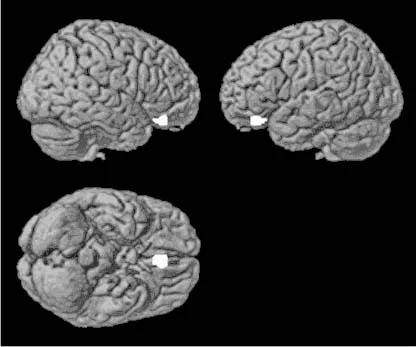

This capacity to abstract seems to operate even at the judgmental level. It has, for example, been shown that judgment of a painting as beautiful correlates with heightened activity in the orbito-frontal cortex, which is part of the brain’s reward system (Figure 1.6).8 But the heightened activity is not observed with only one category of painting. Landscape paintings that are judged to be beautiful are as potent in heightening the activity there as portrait paintings, still lifes, or abstract works that are judged to be beautiful. The common factor is that the painting is judged to be beautiful.

Figure 1.6. Brain activity related to viewing beautiful paintings. Areas in white show regions of maximum cortical activity when humans rate paintings as being beautiful. (Figure adapted from Kawabata H, Zeki S (2004). Neural correlates of beauty. J Neurophysiol 91: 1699-1705.)

So common is this abstractive capacity that one looks instead for departures from it, for indications that a given brain cell or a given brain area will only respond to a particular example of a particular category of stimulus. One exception is to be found in the brain areas that are activated when we view the picture of someone we love. Here, any face will not do. It has to be a specific person, one with whom we are romantically involved.9 But even in this instance, there probably is an abstractive capacity. It is very likely that the areas will become active regardless of the view of the loved person, that is, whether it is a frontal or a side view. I say likely, because the actual experiment has not been done and, in science, there are surprises aplenty. Yet, from all we know about the cortex, the surprise would be if only a particular view would activate these areas.

Once again, we have in the past drawn only some of the conclusions from these experiments, namely that specific visual areas process specific kinds of visual stimuli or that activity in them correlates with specific mental states. In our enthusiasm for these discoveries, we have failed to emphasize the fact that these areas also abstract, in that they are not concerned with specific portraits or landscapes and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Splendors and Miseries of the Brain

- Title

- Copyright

- List of Figures

- Note to the Reader

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Abstraction and the Brain

- Part II: Brain Concepts and Ambiguity

- Part III: Unachievable Brain Concepts

- Part IV: Brain Concepts of Love

- Notes

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- Plates