![]()

Chapter 1

Ancient Roots

Although there is no direct evidence of technical analysis from ancient civilizations, scattered indirect evidence can be uncovered in early market practices. Bearing in mind that technical analysis is not merely a toolbox of head-and-shoulder-like patterns and MACD-like indicators—as many think of it today—but rather the use of past prices to forecast future ones in the most general sense, we find evidence of it in Babylonian price records, Greek market sentiment assessments, and Roman seasonality patterns. Our predecessors not only followed market prices but also made conscious attempts to measure supply/demand imbalances in price data and react to them for their profit, often combining their insights with “data” from fundamental nature or astrology. It should come as no surprise that in ancient times technical forecasting methods were inextricably linked with and in some cases arose from trading and speculation; hence in this chapter we review them side by side.

The Beginnings

People trade. During the late preceramic Neolithic, which is when the settled village life began and plants and animals were domesticated, the settlers from the Jordan Valley engaged in exchange of local resources—such as salt, bitumen, and sulfur—with nomads, as well as in the long-distance trade of obsidian, and domesticated wheat and sheep with the Central Anatolian Plateau and the Zagros-Taurus arc (a mountain range situated between Europe, Asia, and the Levantine corridor to Afr ica).1 In the ceramic phases of the Neolithic, settlers formed agricultural villages in the Zagros Valley while nomadic herders established encampments in the higher elevations. Although there is no evidence of markets in the Zagros during the sixth millennium B.C., the villagers traded grain, flour, fruit, vegetables, and crafts for the nomads’ butter, wool, lambskins, and livestock. Long-distance trade expanded too, to include a variety of new materials such as alabaster, marble, cinnabar, wood, limestone, greenstone, and iron oxides.2 In the later ceramic phases of the Neolithic, around 5000 B.C., villages became highly specialized, and towns or temple centers, possibly equipped with markets, came into being. Long-distance trade flourished like never before, spanning a distance of 1,500 miles and a striking variety of raw mater ials.3

During the early Bronze Age, specifically in the twenty-fourth century B.C, Sargon the Great established the first Mesopotamian empire with its capital at Agade and with the city’s temple serving as the center of the empire’s economic life. The merchant officially worked for the temple and pursued his private entrepreneurial activities on the side. As political power became more secular, the merchant’s domain extended to the palace as well.4 Sumerian epic literature, including the Epic of Gilgamesh, abounds in the allusions to the commercial realities of this per iod.5 After the fall of the last one of these empires, the Third Dynasty of Ur, at around 2000 B.C., numerous and decentralized city-states emerged, each ceremonially headed by its own king but in reality run by the merchants. The same merchants established trading colonies in Anatolia, such as the famous karum Kanesh. 6 In the ensuing Old Babylonian period, trade was in the hands of so-called takamaru whose role encompassed that of merchants, brokers, merchant bankers, money lenders, and government agents. Takamaru dealt in slaves, foodstuffs, wool, timber, garments, textiles, grain, wine, metals, building materials, and cattle and horses. They would either do the trading themselves or loan money to others to go on trading journeys for them.7

The Late Bronze Age was characterized by a rigid political structure, and all trading activities were controlled by the palace.8 In the Iron Age, political power became decentralized and the large palace-towns of the Bronze Age were replaced by numerous, diffuse settlements extending to previously unpopulated areas. Needless to say, both overland and sea trade benefited enormously. As a result, merchants became more free, both in their business activities and in their physical movement. An Iron Age merchant was no longer a palace official who pursued his own profit as a sideline; he was active mainly for his own profit, and stimulated not by royal order but by perceived market advantages.9

Nowhere was the focus on getting rich so pronounced as in ancient Babylon, an early hotbed of commercial innovation. For example, ancient Babylonians established a system of weights and measures, formalized business deals by introducing contracts written on clay tablets and signed by the parties involved, and invented limited partnerships where one partner would raise capital at home while the other would travel for business. Accumulation of wealth was important not just for kings and temples, but also for private individuals such as the famous Murashu family, who were wealthy bankers from Nippur of the fifth century B.C. In fact, it was at this time that trading evolved to the point of a profession—a trader acted as a middleman or a broker and dealt in products he did not produce.10 It is under such conditions that technical analysis came into being in ancient Babylon.

Before drawing parallels between ancient Babylonian practices and modern-day technical analysis, we must first verify that prices in those times were not fixed and controlled by the prevailing rulers, but rather were determined in the market through the interaction of buyers and sellers.

First of all, the existence of markets in ancient Mesopotamia is well established. Not unlike today, the word “street” was associated with the market; for example, Sumerian tablets from the second millennium document the existence of the sūk shimātim or “commercial street” and note that sāchiru (peddlers, retailers) were selling goods on the “street.”11 The Old Babylonian term bīt machīri “seems to refer to the stall of a merchant . . . small in size . . . and adjacent to other stalls.”12 As markets evolved from ad hoc gatherings to more established fixtures of civic life, so did the words that described them: The Akkadian term machiru, which initially had the abstract meaning “price, market value” and “commercial activity,” acquired the concrete meaning “marketplace” by the beginning of the Old Assyrian and Old Babylonian per iods.13

Chlorite vase with alternating bands of mountain-like motifs and date palm trees, the Gulf region or southern Iran ca. 2700-2350 B.C. Vessels in the same style are found throughout the ancient Near East, evidence of the region’s flourishing long-distance trade.

Source: Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY.

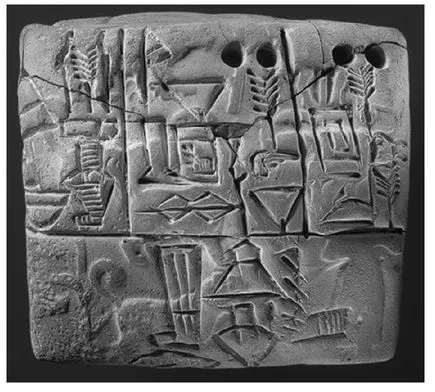

Clay tablet with a seal impression, Mesopotamia ca. 3100-2900 B.C. Commercial record-keeping was widespread in ancient Mesopotamia. This tablet records the distribution of grain by a large temple. The seal impression depicts a man with two dogs on a leash hunting for boars.

Source: Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY.

Moreover, literally thousands of documents from Assyrian trading stations in Anatolia record price fluctuations. For example, one trader reporting about the high price of Babylonian textiles states, “if it is possible to make a purchase which allows you a profit, we will buy for you.”14 Evidence from the third millennium B.C. suggests that prices of barley fluctuated widely. One shekel of silver at different times purchased 10, 20, or 120 quarts of barley, and based on prices, one could then distinguish between mu-he-gal-la or a good growing season and mu-mi-gal-la, a bad one.15 Further evidence suggests that price increases were directly linked to increases in demand. When numerous merchants seeking to buy copper arrived in Anatolia, an Anatolian trader knew the impact this would have on the price of copper and wrote to his associate: “Within the next ten days they will have exhausted its [the palace’s] copper. I shall then buy silver [that is, sell copper] and send it to you.”16 Prophets, too, recognized that increases in supply would lower market prices: When the ninth-century prophet Elisha forecasted the lifting of the Syrian siege, she also noted that “tomorrow about this time a measure of soleth [fine wheat flour] shall be sold for one shekel, and two measures of barley for a shekel in the games of Samar ia.”17

Ancient Babylon

One of the great legacies of ancient Babylon is the trove of clay tablets on which they inscribed their myths, laws, and records. For example, a large number of tablets, some dating back as far as the second millennium B.C., pose textbook-like interest rate problems and provide their solutions.18 In another corpus of tablets, ancient Babylonians kept diaries of astronomical observations and prices of various commodities in the city for almost four centuries. Although the earliest known diary dates back to 651 B.C., it is commonly believed that most of the diaries originated between 747 and 734 B.C., during the reign of Nabonassar. The two earliest diaries, written in 651 and 567 B.C., covered 12 months each.19 Later diaries spanned various lengths of time, ranging from days, weeks, months, or even years. A typical full-sized diary covered either an entire Babylonian year or the first half of it.20

Slotsky characterizes the Mesopotamian records of the market values of commodities as an old and continuous tradition that spanned not only astronomical diaries but also literary works and commemorative establishments.21 To illustrate her point, she points to the Old Babylonian royal inscriptions that listed “ideal” commodity prices in order to “propagate the image of a prosperous reign.”22 Among her other examples are the Laws of Ešnunna and the Hittite Law Code, both of which specified legal prices for various commodities. Other sources of commodity prices include the Chronicle of Market Prices as well as literary texts such as the Coronation Prayer of Assurbanipal and the Curse of Agade. 23

The basic unit of money was the shekel of silver, and prices were quoted as the amount of commodity that one shekel could buy. For example, one diary records the following price quotation: “This month, the equivalent for one shekel of wrought silver was barley, 2

pān 4

sūt 3

qa.”

24 Continuously throughout the centuries, the diaries document the values of the same six commodities—barley, dates, mustard /cuscuta, cress/cardamom, sesame, and wool—a testament to their importance in ancient Babylon. As Slotsky explains:

All six commodities were staples. Barley, dates, sesame, and wool were in widespread use since earliest times and for millennia maintained their economic role as units of payment and exchange. Mustard/cuscuta and cress/cardamom grew to become commodities of great significance, especially in the first millennium, because of their popularity in the Mesopotamian diet and their widespread use in medicine. All were of domestic origin, all were storable, and all were raw materials from which other basics were derived.25

During the four hundred years of their production, the layout of the diaries did not change much. They typically start with a title, which specifies the time range covered by the diary, such as, “Diary from month I to the end o...