- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Christianities in Asia

About this book

Christianity in Asia explores the history, development, and current state of Christianity across the world's largest and most populous continent.

- Offers detailed coverage of the growth of Christianity within South Asia; among the thousands of islands comprising Southeast Asia; and across countries whose Christian origins were historically linked, including Vietnam, Thailand, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and Korea

- Brings together a truly international team of contributors, many of whom are natives of the countries they are writing about

- Considers the Middle Eastern countries whose Christian roots are deepest, yet have turbulent histories and uncertain futures

- Explores the ways in which Christians in Asian countries have received and transformed Christianity into their local or indigenous religion

- Shows Christianity to be a vibrant contemporary movement in many Asian countries, despite its comparatively minority status in these regions

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Christianities in Asia by Peter C. Phan, Peter C. Phan,Peter C. Phan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Cristianismo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: Asian Christianity/Christianities

“Asian Christianity” or “Asian Christianities”? Both the singular and the plural forms are correct, depending on the perspective. From the essentialist viewpoint, it is proper to speak of “Christianity” since the basic Christian beliefs and practices – as distinct from those of, for instance, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam, to mention just the three largest religions in Asia – are the same among all Christian communities in Asia. Historically, however, these same Christian beliefs and practices have been understood, expressed, and embodied in a dizzying variety of ways. This Christian multiformity is a function of the enormous geographical, socio-political, historical, cultural, and religious diversity of the continent called Asia.

Which Asia?

With two thirds of the world's six-billion population, Asia is the largest and most populous continent.1 With Europe as a peninsula of the Eurasian landmass on its west, Asia lies, on its western limits, along the Urals, the Ural River, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, the Black Sea, the Bosporus and the Dardanelles straits, and the Aegean Sea. On its south-western side, it is separated from Africa by the Suez Canal between the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. In its far northeastern part, i.e., Siberia, it is separated from North America by the Bering Strait. In the south, Asia is bathed by the Gulf of Aden, the Arabian Sea, and the Bay of Bengal; on the east, by the South China Sea, East China Sea, Yellow Sea, Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk, and Bering Sea; and on the north, by the Arctic Ocean.

As a continent, Asia is conventionally divided into five regions: Central Asia (mainly the Republics of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmekistan, and Uzbekistan); East Asia (mainly China Japan, Korea, and Taiwan); South Asia (mainly Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka); South-East Asia (mainly Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam); and South-West Asia (the countries of the Middle East, Near East, or West Asia).2

Asia is the land of extreme contrasts. It has both the world's highest peak, Mt. Everest, and its lowest point, the Dead Sea. Climatically, the continent ranges through all extremes, from the torrid heat of the Arabian Desert to the arctic cold of Siberia and from the torrential rains of monsoons to the bone-dry aridity of the Tarim Basin.

Asia's geographical and climactic extremes are matched by linguistic, ethnic, economic, political, cultural, and religious ones. More than 100 languages and more than 700 languages are spoken in the Philippines and Indonesia respectively, whereas only one is spoken in Korea. Ethnically, India and China are teeming with diversity, whereas Vietnam is predominantly homogeneous. Economically, Asia has one of the richest countries (Japan) and the poorest ones on Earth (e.g., North Korea, Cambodia, and Laos). Politically, it contains the largest democratic and the largest communist governments in the world, India and China respectively. Along with linguistic, ethnic, economic, and political diversity come extremely diverse cultures, which are also among the oldest and the richest. Religiously, Asia is the cradle of all world religions. Besides Christianity, other Asian religions include Bahá’í, Bön, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, Hinduism, Islam, Jainism, Shinto, Sikhism, and Zoroastrianism, and innumerable tribal religions.3

Which Christianity?

It is within the context of these mind-boggling diversities – geographic, linguistic, ethnic, economic, political, cultural, and religious – that “Christianity in Asia” should be broached. One of the bitter ironies of Asian Christianity is that though born in (South-West) Asia, it returned to its birthplace as a foreign religion, or worse, the religion of its colonizers, and is still being widely regarded as such by many Asians. But such perception of Christianity as a Western religion imported to Asia by Portuguese and Spanish colonialists in the sixteenth century, and later by other European countries such as Britain, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, and lastly by the United States, belies the ancient roots of Christianity in Asia.

First of all, Christianity may be said to be an Asian religion since it was born in Palestine, part of West Asia or the Middle East. Furthermore, though West Asia is dominated by Islam, it was, until the Arab conquest in the seventh century, the main home of Christianity. But even Asian Christians outside West Asia can rightly boast of an ancient and glorious heritage, one that is as old as the apostolic age. The conventional image of Christianity as a Western religion, that is, one that originated in Palestine but soon moved westward, with Rome as its final destination, and from Rome as its epicenter, Western Christianity sent missionaries worldwide, ignores the fact that in the first four centuries of Christianity's existence, the most successful fields of mission were not Europe but Asia and Africa, with Syria as the center of gravity.

More specifically, Indian Christianity can claim apostolic origins, with St. Thomas and/or St. Bartholomew as its founder(s). Chinese Christianity was born in the seventh century, with the arrival of the East Syrian/Nestorian monk Aloben during the T'ang dynasty. Christianity arrived in other countries such as Japan, the Philippines, and Vietnam in the sixteenth century in the wave of Spanish and Portuguese colonialism. For Korea, on the contrary, Christianity was first brought into the country toward the end of the eighteenth century, not by foreigners but by a Korean, Peter Lee Seung-hun (or Sunghoon Ri), upon his return from Beijing. As for the Pacific Islands, Christianity reached them in the middle of the sixteenth century during the Spanish expeditions from Latin America to the Phillippines and in the late seventeenth century to the Marianas.

Today, in Asia, Christians predominate in only two countries, namely, the Philippines and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (East Timor) – over 85% of their populations are Catholic. In other countries, especially China, India, and Japan, to name the most populous ones, and in countries with a Muslim majority such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Pakistan, and in those where Buddhism predominates such as Cambodia, Hong Kong, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam, Christians form but a minuscule portion of the population. However, despite their minority status, Christians' presence is highly influential, especially in the fields of education, health care, and social services.

In addition to its minority status, Asian Christianity is also characterized by ecclesial diversity, so that it is more accurate to use “Christianities” in the plural to describe it. Because of its past extensive missions in Asia, Roman Catholicism is the largest denomination. Within the Roman Catholic Church, of great importance is the Federation of Asian Bishops' Conferences (FABC), which has served since 1970s, through its general assemblies and several permanent offices, as a clearing house for theological reflection and pastoral initiatives. Older than the Roman Catholic Church is the Malabar Church of India (“Saint Thomas Christians”). The Orthodox Church also has a notable presence in China, Korea, and Japan. The Anglican Church (including the Anglican Church of Canada) is well represented, especially in Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, and Pakistan. Various Protestant Churches also flourish in almost all Asian countries, e.g., the Baptists (especially in North India), the Lutherans, the Mennonites, the Methodists, the Presbyterians (especially in Korea), and the Seventh-Day Adventists. In addition, the number of Pentecostals and charismatics has recently grown by leaps and bounds, particularly among ethnic minorities and disenfranchized social classes. The Yoido Full Gospel Church, located in Seoul, Korea, is the largest Pentecostal church in the world, with over half a million members. Finally, there are numerous indigenous offshoots, inspired by nationalism, charismatic leadership, or by the “Three Self Movement” (self-support, self-propagation, and self-government). Among the most famous are the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (founded by Gregorio Aglipay in 1902), and the Iglesia ni Cristo (founded by Felix Ysagun Manalo in 1914), both in the Philippines, and the China Christian Council (and within it, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement of Protestant Churches in China and the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, founded in 1954 and 1956 respectively).

Introducing Asian Christianities

Curiously, despite the growing importance of Asia and Asian Christianities, there has been a dearth of books that deal with Asian Christianity as a whole and as a contemporary religious movement. There are of course notable histories of Christian missions in Asia and learned monographs on the history of Christianity on individual countries. This volume intends to fill the lacuna of popular introductions to Asian Christianity by presenting a panorama of Asian Christianity as a world religion. It is not a history of Western missions in Asia, though such history will serve as a necessary historical context. Rather, it is on how Christians in Asia have received and transformed Christianity into a local or indigenous religion, with their own ecclesiastical structures, liturgy and prayers, spirituality, theology, art and architecture, music and song and dance, often in dialogue with Asian cultures and religions. The purpose is to help readers gain a sense of Asian Christianity/Christianities as a vibrant contemporary religion.

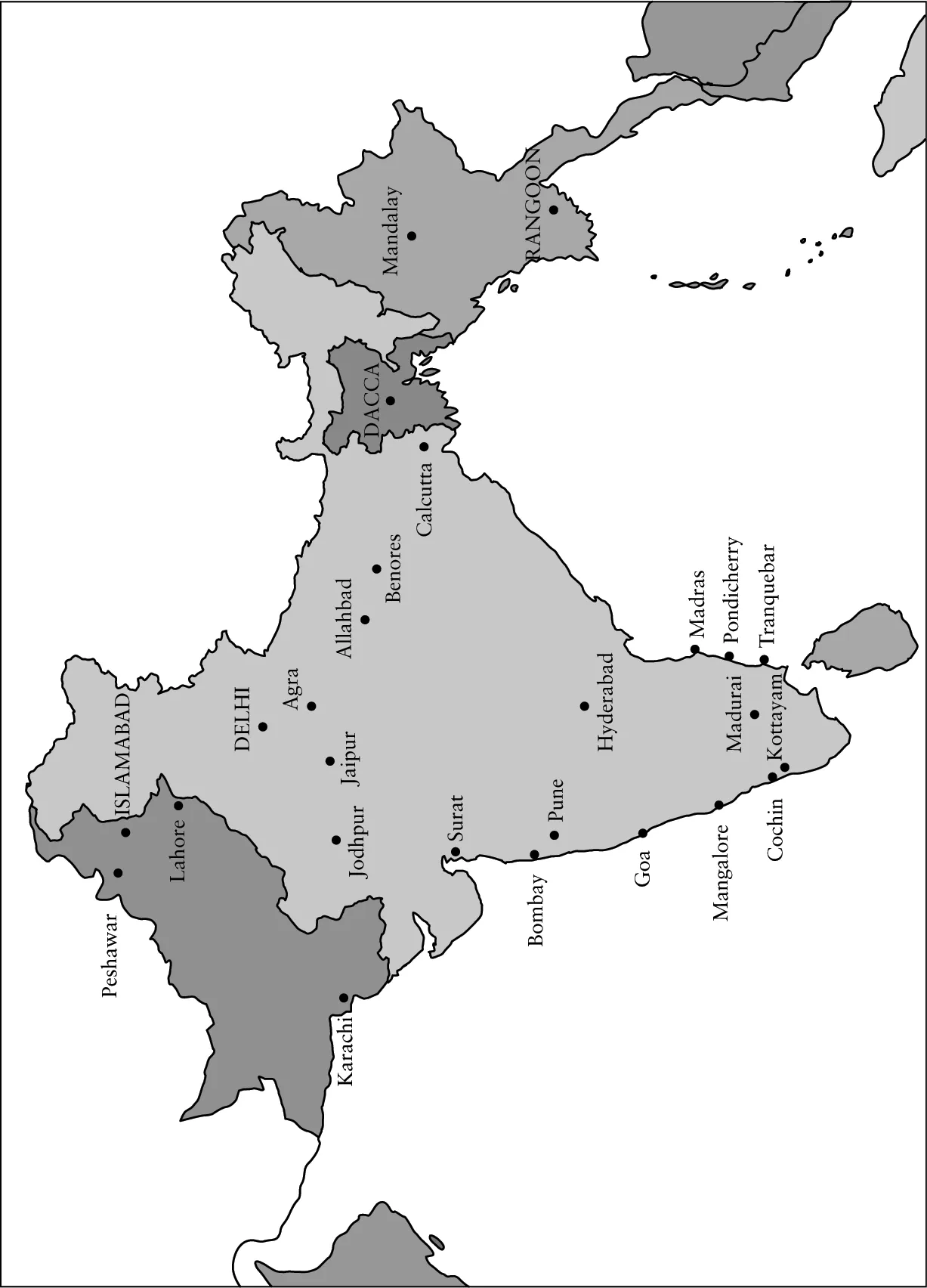

The chapters are grouped together in terms of geographical proximity and cultural and religious affinity. The first three deal with countries in South Asia (India and Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar, and Sri Lanka). The next three describe Christianity in countries lying next to each other as collections of thousands of islands in South-East Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, and the Philippines). The next five consider the countries whose Christian beginnings were historically linked together: Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, China, Mongolia, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan; Japan, and Korea. The last chapter studies the countries in which Christianity has its roots, its earliest developments, and sadly, its most turbulent and uncertain history.

Despite their extreme diversities, there is a golden thread that ties these Asian countries together, and that is, their religious traditions. As mentioned above, Asia is the cradle of all major religions. Understanding how these religions – including Christianity – originated and continue to exist as living institutions in Asia is not only an intellectual obligation but also an indispensable means for peacebuilding and reconciliation in the continent which is currently wracked by violence. The roots of violent conflicts among groups and nations are always many and multiple, and while these conflicts are invariably fueled by political, economic, and military interests, religious claims are almost never absent, especially where a particular religion is adopted as the state religion and its beliefs and practices of a particular religion are imposed as the social, legal, and cultural framework of the civil society. Even when a particular war is first engaged on purely secular grounds, it will not be long before leaders on opposing sides will invoke God's name and power to justify and even bless it. The war will be painted as an apocalyptic struggle between good and evil, and religious demagogues and unscrupulous politicians will stoke religious zeal to mobilize believers for a holy war against their enemies. Participating in war is blessed as a holy service to faith and to be killed, especially in suicide bombing, is celebrated as martyrdom. This is a tragic fact in the history of Asian religions – Asian Christianity included.

But religions – including Christianity – in Asia have also contributed immensely to the spiritual and material well-being of the Asian peoples, and where there is violence and hatred, religions have functioned as an indispensable and effective partner in peacemaking and reconciliation. The so-called “conflict of civilizations” cannot be resolved without the harmony of religions. This too is a salutary and hopeful lesson of the history of Asian religions – including Asian Christianity.

Notes

1. I am aware that in terms of physical geography (landmass) and geology (tectonic plate), Europe and Asia form one “continent.” In terms of human geography, however, Europe and Asia have been conventionally treated as different continents, the latter divided into East Asia (the Orient), South Asia (British India), and the Middle East (Arabia and Persia). In this book the term “continent” of Asia is used in this generic sense. As mentioned in the text below, today Asia is divided into five regions (geographers rarely speak of ‘“North Asia”). The adjective “Asian” is also confusing. In American English, it refers to East Asian (Orientals), whereas in British English, it refers to South Asia (India). Sometimes, the term is restricted to countries of the Pacific Rim. Here “Asia” refers to East Asia, South Asia, South-East Asia, and the Middle (Near) East or South-West or West Asia.

2. This book will not deal with Christianity in Central Asia.

3. For a succinct presentation of the Asian context in which Christian mission is carried out, see John Paul II's apostolic exhortation Ecclesia in Asia (1999), nos. 5–9. The text is available in Phan, P.C. (ed.) The Asian Synod: Texts and Commentaries, Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2002, pp. 286–340.

Chapter 2

India, Pakisttwdb, Bangladesh, Burma/Myanmar

Caste, class, and ethnicity, local and foreign missions, contested contextualization, inter- and intra-religious pluralism, colonialism, politics, poverty, nationalism: this sample list gives some indication of the complexity of Christianity in South Asia, home to the most populous country in Asia (India), one of the poorest (Burma/Myanmar), and to two regularly threatened by floods or internal strife (Bangladesh and Pakistan). The above catalogue reflects tensions between groups of believers, and between believers and the scriptural teachings they confess.

It is important to make clear at the outset that sociological tensions and chasms between faith and practice are present in every Christian community, as in any other religious community, across the globe. However, certain elements are admittedly peculiar to South Asian Christianity: a close identification with minorities in North-East India, Bangladesh, and Burma/Myanmar; the widespread acceptance of the Vedanta caste system, especially in India and Pakistan, where four fifths of Christians are despised dalits; and an uncertain or clearly subordinated position for women. They are the local equivalents of the “blasphemies” associated with class, gender, race and ethnicity which form the basis of powers and principalities, ecclesial and otherwise, across the world.1

This chapter will focus on the socio-cultural and liturgical interaction between Christianity and its contexts in mainland South Asia. There are three reasons why this crossroads of languages, peoples, and traditions is currently one of the most important regions for sociological and theological reflection on Christianity or, more properly, a collage of contextualized Christianities.

The first, and simplest, reason is longevity. Christians have been present in South Asia longer than almost anywhere else outside the Eastern Mediterranean.2 Orthodoxy first came to Taxila (Pakistan) and to Kerala (India) in 52 CE (or perhaps a little later), where they had to deal with the local Jewish communities, just as their stay-at-home cousins in Palestine were negotiating with and, if necessary, moving away from Judaism. This ancient history and the processes of religious negotiation are not only a rich source of historical knowledge but also contain lessons of immense value for Christianity's encounter with modernity.

Secondly, all Christian denominations in their various versions are present throughout South Asia. With its firm ties both to Damascus and to the upper Kerala castes, Orthodoxy is still an economic and religious controlling force. Pentecostalism had flamed in Assam in1905, before the Azuza Street Revival in Los Angeles, USA in 1906 claimed precedence, and is now quickly spreading through indirect influence on other mainline churches and through direct local mission and church planting. Portuguese Roman Catholicism of the early sixteenth century essayed to eliminate what they called “paganized” Orthodoxy, an adjective Jesuit missionaries readily used to describe Indian society in general, alleging its incapacity for independent thought, moral order or chastity.3 Faltering by the early nineteenth century,4 the Catholic Church has now resumed the contextualizing task initiated to an extent by Italian missionaries of that earlier period such as Roberto de Nobili and Constanzo Giuseppe B...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Maps

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction: Asian Christianity/Christianities

- Chapter 2: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma/Myanmar

- Chapter 3: Sri Lanka

- Chapter 4: Indonesia

- Chapter 5: Malaysia and Singapore

- Chapter 6: The Philippines

- Chapter 7: Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand

- Chapter 8: Mainland China

- Chapter 9: Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau

- Chapter 10: Japan

- Chapter 11: South Korea

- Chapter 12: The Middle East

- Conclusion: Whither Asian Christianities?

- Index