eBook - ePub

The Little Book That Builds Wealth

The Knockout Formula for Finding Great Investments

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In The Little Book That Builds Wealth, author Pat Dorsey—the Director of Equity Research for leading independent investment research provider Morningstar, Inc.—reveals why competitive advantages, or economic moats, are such strong indicators of great long-term investments and examines four of their most common sources: intangible assets, cost advantages, customer-switching costs, and network economics. Along the way, he skillfully outlines this proven approach and reveals how you can effectively apply it to your own investment endeavors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Little Book That Builds Wealth by Pat Dorsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Investments & Securities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Economic Moats

What’s an Economic Moat, and

How Will It Help You Pick

Great Stocks?

How Will It Help You Pick

Great Stocks?

FOR MOST PEOPLE, it’s common sense to pay more for something that is more durable. From kitchen appliances to cars to houses, items that will last longer are typically able to command higher prices, because the higher up-front cost will be offset by a few more years of use. Hondas cost more than Kias, contractor-quality tools cost more than those from a corner hardware store, and so forth.

The same concept applies to the stock market. Durable companies—that is, companies that have strong competitive advantages—are more valuable than companies that are at risk of going from hero to zero in a matter of months because they never had much of an advantage over their competition. This is the biggest reason that economic moats should matter to you as an investor: Companies with moats are more valuable than companies without moats. So, if you can identify which companies have economic moats, you’ll pay up for only the companies that are really worth it.

To understand why moats increase the value of companies, let’s think about what determines the value of a stock. Each share of a company gives the investor a (very) small ownership interest in that firm. Just as an apartment building is worth the present value of the rent that will be paid by its tenants, less maintenance expenses, a company is worth the present value2 of the cash we expect it to generate over its lifetime, less whatever the company needs to spend on maintaining and expanding its business.

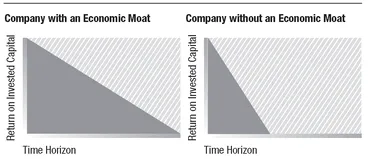

So, let’s compare two companies, both growing at about the same clip, and both employing about the same amount of capital to generate the same amount of cash. One company has an economic moat, so it should be able to reinvest those cash flows at a high rate of return for a decade or more. The other company does not have a moat, which means that returns on capital will likely plummet as soon as competitors move in.

The company with the moat is worth more today because it will generate economic profits for a longer stretch of time. When you buy shares of the company with the moat, you’re buying a stream of cash flows that is protected from competition for many years. It’s like paying more for a car that you can drive for a decade versus a clunker that’s likely to conk out in a few years.

In Exhibit 1.1, time is on the horizontal axis, and returns on invested capital are on the vertical axis. You can see that returns on capital for the company on the left side—the one with the economic moat—take a long time to slowly slide downward, because the firm is able to keep competitors at bay for a longer time. The no-moat company on the right is subject to much more intense competition, so its returns on capital decline much faster. The dark area is the aggregate economic value generated by each company, and you can see how much larger it is for the company that has a moat.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Company with an Economic Moat versus a Company without a Moat

So, a big reason that moats should matter to you as an investor is that they increase the value of companies. Identifying moats will give you a big leg up on picking which companies to buy, and also on deciding what price to pay for them.

Moats Matter for Lots of Reasons

Why else should moats be a core part of your stock-picking process?

Thinking about moats can protect your investment capital in a number of ways. For one thing, it enforces investment discipline, making it less likely that you will overpay for a hot company with a shaky competitive advantage. High returns on capital will always be competed away eventually, and for most companies—and their investors—the regression is fast and painful.

Think of all the once-hot teen retailers whose brands are now deader than a hoop skirt, or the fast-growing technology firms whose competitive advantage disappeared overnight when another firm launched a better widget into the market. It’s easy to get caught up in fat profit margins and fast growth, but the duration of those fat profits is what really matters. Moats give us a framework for separating the here-today-and-gone-tomorrow stocks from the companies with real sticking power.

Also, if you are right about the moat, your odds of permanent capital impairment—that is, irrevocably losing a ton of money on your investment—decline considerably. Companies with moats are more likely to reliably increase their intrinsic value over time, so if you wind up buying their shares at a valuation that (in hindsight) is somewhat high, the growth in intrinsic value will protect your investment returns. Companies without moats are more likely to suffer sharp, sudden decreases in their intrinsic value when they hit competitive speed bumps, and that means you’ll want to pay less for their shares.

Companies with moats also have greater resilience, because firms that can fall back on a structural competitive advantage are more likely to recover from temporary troubles. Think about Coca-Cola’s disastrous launches of New Coke years ago, and C2 more recently—they were both complete flops that cost the company a lot of money, but because Coca-Cola could fall back on its core brand, neither mistake killed the company.

Coke also was very slow to recognize the shift in consumer preferences toward noncarbonated beverages such as water and juice, and this was a big reason behind the firm’s anemic growth over the past several years. But because Coke controls its distribution channel, it managed to recover somewhat by launching Dasani water and pushing other newly acquired noncarbonated brands through that channel.

Or look back to McDonald’s troubles in the early part of this decade. Quick-service restaurants are an incredibly competitive business, so you’d think that a firm that let customer service degrade and failed to stay in touch with changing consumer tastes would have been complete toast. And in fact, that’s the way the business press largely portrayed Mickey D’s in 2002 and 2003. Yet McDonald’s iconic brand and massive scale enabled it to retool and bounce back in a way that a no-moat restaurant chain could not have done.

This resiliency of companies with moats is a huge psychological backstop for an investor who is looking to buy wonderful companies at reasonable prices, because high-quality firms become good values only when something goes awry. But if you analyze a company’s moat prior to it becoming cheap—that is, before the headlines change from glowing to groaning—you’ll have more insight into whether the firm’s troubles are temporary or terminal.

Finally, moats can help you define what is called a “circle of competence.” Most investors do better if they limit their investing to an area they know well—financialservices firms, for example, or tech stocks—rather than trying to cast too broad a net. Instead of becoming an expert in a set of industries, why not become an expert in firms with competitive advantages, regardless of what business they are in? You’ll limit a vast and unworkable investment universe to a smaller one composed of high-quality firms that you can understand well.

You’re in luck, because that’s exactly what I want to do for you with this book: make you an expert at recognizing economic moats. If you can see moats where others don’t, you’ll pay bargain prices for the great companies of tomorrow. Of equal importance, if you can recognize no-moat businesses that are being priced in the market as if they have durable competitive advantages, you’ll avoid stocks with the potential to damage your portfolio.

The Bottom Line

1. Buying a share of stock means that you own a tiny—okay, really tiny—piece of the business.

2. The value of a business is equal to all the cash it will generate in the future.

3. A business that can profitably generate cash for a long time is worth more today than a business that may be profitable only for a short time.

4. Return on capital is the best way to judge a company’s profitability. It measures how good a company is at taking investors’ money and generating a return on it.

5. Economic moats can protect companies from competition, helping them earn more money for a long time, and therefore making them more valuable to an investor.

Chapter Two

Mistaken Moats

Don’t Be Fooled by These Illusory

Competitive Advantages.

Competitive Advantages.

THERE’S A COMMON CANARD in investing that runs, “Bet on the jockey, not on the horse”—the notion is that the quality of a management team matters more than the quality of a business. I suppose that in horse racing it makes sense. After all, racing horses are bred and trained to run fast, and so the playing field among horses seems relatively level. I may be on thin ice here, having never actually been to a horse race, but I think it’s fair to say that mules and Shetland ponies don’t race against thoroughbreds.

The business world is different. In the stock market, mules and Shetland ponies do race against thoroughbreds, and the best jockey in the world can’t do much if his mount is only weeks from being put out to pasture. By contrast, even an inexperienced jockey would likely do better than average riding a horse that had won the Kentucky Derby. As an investor, your job is to focus on the horses, not the jockeys.

Why? Because the single most important thing to remember about moats is that they are structural characteristics of a business that are likely to persist for a number of years, and that would be very hard for a competitor to replicate.

Moats depend less on managerial brilliance—how a company plays the hand it is dealt—than they do on what cards the company holds in the first place. To strain the gambling analogy further, the best poker player in the world with a pair of deuces stands little chance against a rank amateur with a straight flush.

Although there are times when smart strategies can create a competitive advantage in a tough industry (think Dell or Southwest Airlines), the cold, hard fact is that some businesses are structurally just better positioned than others. Even a poorly managed pharmaceutical firm or bank will crank out long-term returns on capital that leave the very best refiner or auto-parts company in the dust. A pig with lipstick is still a pig.

Because Wall Street is typically so focused on short-term results, it’s easy to confuse fleeting good news with the characteristics of long-term competitive advantage.

In my experience, the most common “mistaken moats” are great products, strong market share, great execution, and great management. These four traps can lure you into thinking that a company has a moat when the odds are good that it actually doesn’t.

Moat . . . or Trap?

Great products rarely make a moat, though they can certainly juice short-term results. For example, Chrysler virtually printed money for a few years when it rolled out the first minivan in the 1980s. Of course, in an industry where fat profit margins are tough to come by, this success did not go unnoticed at Chrysler’s competitors, all of whom rushed to roll out minivans of their own. No structural characteristic of the automobile market prevented other firms from entering Chrysler’s profit pool, so they crashed the minivan party as quickly as possible.

Contrast this experience with that of a small auto-parts supplier named Gentex, which introduced an automatically dimming rearview mirror not too long after Chrysler’s minivans arrived on the scene. The auto-parts industry is no less brutal than the market for cars, but Gentex had a slew of patents on its mirrors, which meant that other companies were simply unable to compete with it. The result was fat profit margins for Gentex for many years, and the company is still posting returns on invested capital north of 20 percent more than two decades after its first mirror hit the market.

One more time, with feeling: Unless a company has an economic moat protecting its business, competition will soon arrive on its doorstep and eat away at its profits. Wall Street is littered with the dead husks of companies that went from hero to zero in a heartbeat.

Remember Krispy Kreme? Great doughnuts, but no economic moat—it is very easy for consumers to switch to a different doughnut brand or to pare back their doughnut consumpti...

Table of contents

- Little Book Big Profits Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One - Economic Moats

- Chapter Two - Mistaken Moats

- Chapter Three - Intangible Assets

- Chapter Four - Switching Costs

- Chapter Five - The Network Effect

- Chapter Six - Cost Advantages

- Chapter Seven - The Size Advantage

- Chapter Eight - Eroding Moats

- Chapter Nine - Finding Moats

- Chapter Ten - The Big Boss

- Chapter Eleven - Where the Rubber Meets the Road

- Chapter Twelve - What’s a Moat Worth?

- Chapter Thirteen - Tools for Valuation

- Chapter Fourteen - When to Sell

- Conclusion