![]()

Part I

Credit Background and Credit Derivatives

![]()

1

Credit Debt and Other Traditional Credit Instruments

The reader is assumed to be familiar with government bonds, with the LIBOR market and to have had some familiarity with traditional credit instruments (bonds and loans). The following sections briefly review these areas and develop some techniques for the analysis of credit risk - particularly in relation to credit portfolios.

1.1 BONDS AND LOANS; LIBOR RATES AND SWAPS; ‘REPO’ AND GENERAL COLLATERAL RATES

1.1.1 Bonds and Loans

A bond (Bloomberg definition) is a certificate of debt issued by a government or corporation with the promise to pay back the principal amount as well as interest by a specified future date. A loan is a broader concept than a bond - it is a sum of money lent at interest. In practice bonds are usually traded instruments (at least in principle) whereas loans are often private agreements between two or more parties (usually a corporate entity and a bank). There has been a growing market recently in syndicated loans as opposed to bilateral loans. Traditionally loans have been bilateral agreements between the borrower (typically a corporate entity) and a lender (typically a bank but often a private individual) the terms of which can be very varied including various options and restrictions on the borrower’s use of the money or financial performance. A syndicated loan is offered by a group of lenders (a ‘syndicate’) who work together to provide funds for a single borrower and share the risk - unlike bilateral loans. Typically there is a lead bank or underwriter of the loan, known as the ‘arranger’, ‘agent’, or ‘lead lender’. The term ‘leveraged loan’ simply means a high-yield loan (high-risk borrower) and apart from the higher spread on such loans there are no other new features. There has also been growing market in secondary trading of bilateral loans - where the cashflows under the loan agreement are assigned (sold) to a third party. For this to be possible the loan agreement has to allow this transfer to take place; such loans are assignable loans. Many loans - although this is becoming less common than historically - are non-assignable (the ownership of the cashflows cannot be transferred). Some loans are non-assignable except in default. (We see later that these variations have implications for the credit derivatives market - they potentially restrict the deliverability of some debt into default swap contracts.) The syndicated loan market has sought standardisation of loan terms and restrictions - this is covered in more detail later, but syndicated loans are usually immediately callable by the borrower, contain a wide range of restrictions on the borrowers financial performance (covenants) and are often but not always issued through CLO structures to investors.

When we speak of a credit bond (or loan) we are explicitly recognising the risk that the payments promised by the borrower may not be received by the lender - an event we refer to as default (we discuss this further below).

1.1.2 BBA LIBOR and Swaps

According to the British Bankers’ Association, ‘LIBOR stands for the London Interbank Offered Rate and is the rate of interest at which banks borrow funds from other banks, in marketable size, in the London interbank market’. BBA LIBOR rates are quoted for a number of currencies and terms up to one year, and are derived from rates contributed by at least eight banks active in the London market. (See http://www.bba.org.uk for more information.) LIBOR rates clearly refer to risky transactions - the lending of capital by one bank to another - albeit of low risk because of the short-term nature of the deal and also the high quality of the banks contributing to the survey.

An interest rate swap contract (Bloomberg) is ‘a contract in which two parties agree to exchange periodic interest payments, especially when one payment is at a fixed rate and the other varies according to the performance of a reference rate, such as the prime rate’. Typically interest rate swaps are for periods of more than a year, and usually the reference rate is LIBOR. The swap itself is a risky deal although on day one the value of the fixed flows equals the value of the floating payments, so the risk is initially zero. Risk emerges as interest rate levels change, affecting the value of the floating and fixed payments differently. (Expected risk at a forward date will not be zero if the interest rate curve is not flat though will typically be small in relation to the value of one of the legs of the swap.) Swaps are low risk, although swap rates themselves are risky rates largely because the reference floating rate itself (LIBOR) is a risky rate.

1.1.3 Collateralised Lending and Repo

Banks often use listed securities as collateral (assets pledged as security) against cash they borrow to meet other needs. Such lending (of securities) and borrowing (of cash) is referred to as collateralised borrowing and the rate of interest applicable to generic collateral is the general collateral rate (GC). Typically such collateralised lending agreements are for short terms (they may be on a rolling overnight basis) and the GC rate itself is usually a few (2-7) basis points below LIBOR rates.

The reader should note several things at this point.

1. Any structured product created by a bank can in principle be securitised and used as collateral to obtain the cash required to finance the transaction. General collateral rates are therefore key in determining the cost of any structured deal (including credit derivatives).

2. GC rates are not readily available - they are known by the repo trading desk but not made publicly available. Some US repo rates are published on Reuters. The European Banking Federation sponsors the publication of EUREPO, a set of GC repo rates relating to European government bonds. However, LIBOR rates are very easy to obtain and are also close to GC.

3. Investment banks typically mark their positions to market by discounting off the LIBOR and swap curve (because LIBOR is the financing cost, and for arbitrage reasons - see, for example, Chapter 9).

LIBOR (and swap) rates are therefore key to the development of the pricing of credit derivatives.

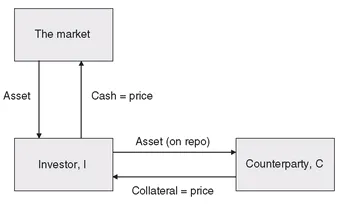

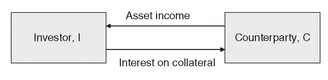

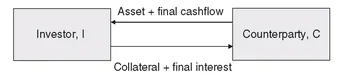

We shall look at the deal underlying collateralised lending (a ‘repo’) in detail since an understanding of this issue is required later. A ‘repo’ or repurchase agreement is a contract giving the seller of an asset the right, and the obligation, to buy it back at a predetermined price on a predetermined date. The borrower of cash (‘lender’ of the asset) sells the asset to a counterparty under the repo contract and receives cash (equal to the market value of the asset2). Prior to termination of the deal any cashflows generated by the asset are passed on to the original owner of the asset, and the borrower of cash pays interest at a rate specific to that asset - the repo rate. On the termination of the deal the borrower of cash repays the loan and receives the asset back. In the event of default of the asset, the end date of the repo would be accelerated - the asset passes back to the original owner and the debt is repaid. (See Figures 1.1-Figures 1.3.)

Figure 1.1 Repo deal - initial, capital and asset flows.

We can see that, although legal ownership of the asset passes from the original owner, ‘economic ownership’ remains with the original owner (i.e. the original owner of the asset receives all the cashflows from the asset in any eventuality as if he owned that asset).

Typically repo deals are short term - from overnight to a few months.

Figure 1.2 Repo deal - ongoing cashflows.

GC rates are tiered according to the class of asset. There are different GC rates for Government bonds depending on the country of issue; GC rates for corporate bonds are determined by the rating. However, a particular asset - for example, a certain bond - may go ‘special’ on repo. An institution may need to borrow a particular asset (for example, it may have sold the asset short) and may be prepared to ‘pay’ in order to receive that asset. Under the repo deal the institution pledges (lends) cash against the asset it borrows and, if the asset were not special, would receive interest at the GC rate. But if the asset goes special, the repo rate for that asset falls below the GC rate - and may fall to zero or even become negative. (‘Special’ repo rate have an impact on the basis between bonds and default swaps (see Part II).) The borrower of the bond lends cash and therefore receives a sub-LIBOR return on that cash.

Figure 1.3 Repo deal - final capital and asset flows.

1.1.4 Repo as a Credit Derivative

A repo is not traditionally regarded as a credit derivative even if the collateral is a credit risky asset, although it is almost identical to a ‘Total Return Swap’ (see Part II) which is usually classed as a credit derivative. Furthermore, there is a significant and complex embedded credit risk if there is a correlation between the borrower of cash and the reference entity of the collateral (see Parts III and IV). A default of the borrower may cause a sudden drop in the value of the collateral in this case, so the lender of cash is taking on a non-trivial credit derivative risk. A similar risk exists in default swap contracts ...