eBook - ePub

Atomic Structure Prediction of Nanostructures, Clusters and Surfaces

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Atomic Structure Prediction of Nanostructures, Clusters and Surfaces

About this book

This work fills the gap for a comprehensive reference conveying the developments in global optimization of atomic structures using genetic algorithms. Over the last few decades, such algorithms based on mimicking the processes of natural evolution have made their way from computer science disciplines to solid states physics and chemistry, where they have demonstrated their versatility and predictive power for many materials. Following an introduction and historical perspective, the text moves on to provide an in-depth description of the algorithm before describing its applications to crystal structure prediction, atomic clusters, surface and interface reconstructions, and quasi one-dimensional nanostructures. The final chapters provide a brief account of other methods for atomic structure optimization and perspectives on the future of the field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Atomic Structure Prediction of Nanostructures, Clusters and Surfaces by Cristian V. Ciobanu,Cai-Zhuan Wang,Kai-Ming Ho in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technik & Maschinenbau & Werkstoffwissenschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Challenge of Predicting Atomic Structure

The atomic structure is the most important piece of information that is necessary when studying the properties of crystals, surfaces, interfaces, or nanostructures. If the bulk crystal structure of a material or compound is known, this may, under certain conditions, help in determining the structures of surfaces, clusters, or nanowires; however, such knowledge does not at all imply that we automatically know the structure of a surface or of a nanoparticle made out of that material. Often the surfaces and nanostructures adopt very intriguing atomic configurations, especially when their size is small (e.g., small number of atoms for clusters, thin diameter for nanowires, etc.). By now, the structure of many crystals is already known and usually taken for granted, sometimes to the point of considering a surface or a nanostructure as a simple truncation of the bulk material. As we see in other chapters, this is rarely the case at the nanoscale: the structure of atomic small clusters has little (usually nothing) to do with that of the bulk crystalline material!

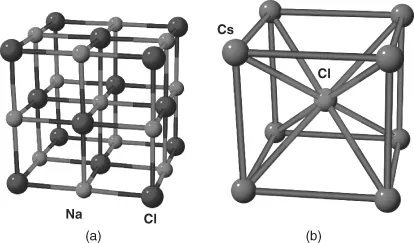

Coming back to the issue of bulk crystal structure, on fundamental grounds, we have to recognize that retrieving the crystal structure from a given material or compound solely from knowing its composition is not an easy or a straightforward task: what determines, say, molybdenum to “choose” a body-centered cubic structure at normal conditions of temperature and pressure, when palladium has a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure and ruthenium adopts a hexagonal close-packed one? Why does NaCl, the common salt, adopt a structure in which both the fcc sublattices of Na and those of Cl are displaced along the side of the conventional cube, but CsCl adopts a different structure even though Cs is in the same group as Na in the periodic table? Granted, one can easily give a partial answer to this question on grounds that the Cs atom, although of same valence as Na, has a larger ionic radius and therefore would tend to have more Cl atoms around it than Na has. Still, what made NaCl adopt its specific structure (Figure 1.1) in the first place? Why are the sodium atoms in NaCl crystal arranged in an fcc structure, could they not have chosen a different arrangement? Some decades ago, John Maddox [1] phrased the problem of determining the crystal structure from its composition as provocation also meant as a statement of fact (or perhaps the other way around):

“One of the continuing scandals in the physical sciences is that it remains impossible to predict the structure of even the simplest crystalline solids from a knowledge of their composition.”

Figure 1.1 The crystal structures of NaCl (a) and CsCl (b).

The scientific community has responded very well to that provocation: now, two and a half decades later, the development of global search algorithms coupled with the increase in available computing power allows us to make the crystal structure predictions from first-principles calculations, starting only with the desired composition. In this chapter, we are going to follow the main milestones that have led to such progress, and then describe the scope and organization of this book.

1.1 Evolution: Reality and Algorithms

What eventually has facilitated the best answer to Maddox's challenge are evolutionary algorithms or genetic algorithms (GAs) for structure prediction. We use these terms interchangeably, although only part of the scientific community does so. Methods to simulate materials thermodynamics already existed (such as simulated annealing [2]): those methods are highly meaningful from a fundamental standpoint. Not only do they simulate the thermodynamics of the material, but, in principle, they may double as ground-state structure prediction methods if the system is run at high enough temperatures and then slowly cooled down. However versatile this approach may seem at the first sight, in its early days it has not always led to ground-state structures due to the tendency to get stuck in metastable local minima. As it turns out, having the materials system go over energetic barriers in the potential energy surface (PES) is not an easy task: in fact, it is extremely time consuming and inefficient. Even if sufficiently slow cooling rates may be achieved for certain systems and ground state is reached, those rates do not serve as universal knowledge to be transferred to other materials.

What has significantly changed this situation are methods that can cross energy barriers with some ease, which have been continuously developed starting in early 1990s. Among those, the GA approaches have been developed now to the point that they make reliable predictions of cluster or crystal structures. In a genetic algorithm, we usually start with a pool of structures (genetic pool) that may or may not have anything to do with the real material structure. Only the nature of the atoms that compose those structures should be chosen as desired.

GAs are simple and generic methods that evolve the structures in this pool according to a certain energetic criterion (or cost function). The evolution proceeds via a set of genetic operations: through these genetic operations, new structures are created from the old ones, their cost functions are evaluated, and the new structures are considered for inclusion in the pool of structures depending on the values of their cost functions. If the energy (cost function) of a new structure is sufficiently low, then that newly created structure will be included in the genetic pool at the expense of an older and less energetically favorable one. It is obvious that the GA procedure, which will be described in more detail throughout this book, is guaranteed to lead to improvements in the structure in the pool. At the very worst, any newly created structure has higher energy than the old ones at any given point, in which case the genetic pool is never updated. However, this never happens if the initial genetic pool is initialized with random structures. The genetic operations, after a sufficient number of applications, will generate structures that are better than the random ones simply by virtue of keeping the pool updated to include structures with low energies.

In a way, the analogy with reality is very clear. Traits (atomic configurations) that are beneficial to the species are propagated in time through the genetic operations, while those that are not lead to creation of specimens that are unfit to survive and eventually die (structures are pushed out of the genetic pool). Although the principle of GA is strikingly close to that encountered in the actual Darwinian evolution of species, we note that in GA for structure optimization the parent structures can pass on not only traits that they themselves have been born with but also traits that they have acquired during the evolution: this is called Lamarckian evolution. In fact, this Lamarckian evolution coupled with the relative simplicity of atomic and molecular systems compared to actual genomes leads to structures that evolved sufficiently fast. In the evolution of species, there is no actual end to the process; that is, there is a continuous adaptation to the environmental conditions of life. However, when using GAs for atomic structure problems, we use them as a way to find a solution, usually a ground-state structure for some given conditions; that is, we use the lowest-energy structure for a given composition and then halt the procedure if the best structure in the genetic pool stops improving after a prescribed number of generations.

1.2 Brief Historical Perspective

The use of GAs as a structure optimization method can be traced back to the work of Hartke [3], who used it for small silicon clusters; another early use of the method was for small molecular clusters [4]. It is interesting to note that in order to keep the algorithm close to the real-life evolution, the structures in those early works were encoded as strings of 0s and 1s, strings that are interpreted as the genomes of the individual structures. Then, new structures would be created from gene splicing in which genetic operators (crossover, mutation) acted on binary strings, bit by bit. As a matter of historical perspective, we have to note that the encoding in the work of Hartke was not done by independently discretizing the space; rather, there was a prescribed set of geometric parameters associated with the cluster that was encoded as a binary string. Although there have been other works benefiting from GA searches in this binary encoding (called genotype representation) [5–7], there are already two problems to be recognized. First, the encoding of space requires a careful definition of certain geometric parameters. Second, because in this encoding GA does not fine-tune on local or global minima, in order to do that one would have to add a minimization step, in real space.

As a response to the first of these two problems, Zeiri [8] described the structures in a genetic pool not as binary strings, but as the collection of position vectors for the atoms. This description removed the arti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Challenge of Predicting Atomic Structure

- Chapter 2: The Genetic Algorithm in Real-Space Representation

- Chapter 3: Crystal Structure Prediction

- Chapter 4: Optimization of Atomic Clusters

- Chapter 5: Atomic Structure of Surfaces, Interfaces, and Nanowires

- Chapter 6: Other Methodologies for Investigating Atomic Structure

- Chapter 7: Perspectives and Outlook

- Index