![]()

1

Introduction to Lifespan Nutrition

Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

- Describe what is meant by a lifespan approach to the study of nutrition and health.

- Discuss the meaning of the term “nutritional status” and describe how optimal nutrition requires a balance of nutrient supply and demand for nutrients in physiological and metabolic processes.

- Show an awareness of the factors that contribute to undernutrition, including limited food supply and increased demands due to trauma or chronic illness.

- Discuss global strategies for the prevention of malnutrition.

- Describe how nutritional status is influenced by the stage of life due to the variation in specific factors controlling nutrient availability and requirements, as individuals develop from the fetal stage through to adulthood.

- Show an appreciation of how anthropometry, dietary assessment, measurements of biomarkers, and clinical examination can be used to study nutritional status in individuals and populations.

- Discuss the need for dietary standards in making assessments of the quality of diet or dietary provision, in individuals or populations.

- Describe the variation in the basis and usage of dietary reference value systems in different countries.

1.1 The lifespan approach to nutrition

The principal aim of this book is to explore relationships between nutrition and health, and the contribution of nutrition-related factors to disease. In tackling this subject, there are many different approaches that could be taken, for example, considering diet and cardiovascular disease, nutrition and diabetes, obesity or immune function as separate and discrete entities, each worthy of their own chapter. The view of this author, along with many others in recent times (Ben-Shlomo and Kuh, 2002) is that the final stages of life, that is, the elderly years, are effectively the products of events that occur through the full lifespan of an individual. Aging is in actuality a continual, lifelong process of ongoing change and development from the moment of conception until the point of death. It is therefore inappropriate to consider how diet relates to chronic diseases that affect adults without allowance for how the earlier life experiences have shaped physiology. The lifespan approach that is used to organize the material in this book essentially asserts three main points:

1 All stages of life from the moment of conception through to the elderly years are associated with a series of specific requirements for nutrition.

2 The consequences of less than optimal nutrition at each stage of life will vary, according to the life stage affected.

3 The nature of nutrition-related factors at earlier stages of life will determine how individuals grow and develop. As a result, the relationship between diet and health in later stages of adult life, to some extent, depends upon events earlier in life. As a result the nature of this relationship may be highly individual.

Although we tend to divide the lifespan into a series of distinct stages, such as infancy, adolescence, early adulthood, middle age, and older adulthood, few of these divisions have any real biological significance and they are therefore simply markers of particular periods within a continuum. There are, however, key events within these life stages, such as weaning, the achievement of puberty, or the menopause, which are significant milestones that mark profound physiological and endocrine changes and have implications for the nature of the nutrition and health relationship. On a continual basis, at each stage of life, individuals experience a series of biological challenges, such as infection or exposure to carcinogens that threaten to disturb normal physiology and compromise health. Within a lifespan approach, it is implicit that the response of the system to each challenge will influence how the body responds at later life stages. Variation in the quality and quantity of nutrition is one of the major challenges to the maintenance of optimal physiological function and is also one of the main determinants of how the body responds to other insults.

In considering the contribution of nutrition-related factors to health and disease across the lifespan, it is necessary to evaluate the full range of influences upon quality and quantity of nutrition and upon physiological processes. This book therefore takes a broad approach and includes consideration of social or cultural influences on nutrition and health, the metabolic and biochemical basis of the diet–disease relationships, the influence of genetics, and, where necessary, provides overviews of the main physiological and cellular processes that operate at each life stage. While the arbitrary distinctions of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood have been used to divide the chapters, it is hoped that the reader will consider this work as a whole. In this opening chapter, we consider some of the basic terms and definitions used in nutrition and lay the foundations for understanding more complex material in the following chapters.

1.2 The concept of balance

Balance is a term frequently used in nutrition and, unfortunately, the precise meaning of the term may differ according to the context and the individual using it. It is common to hear the phrase “a balanced diet” and, indeed, most health education literature that goes out to the general public urges the consumption of a diet that is “balanced.” In this context, we refer to a diet that provides neither too much nor too little of the nutrients and other components of food that are required for normal functioning of the body. A balanced diet may also be viewed as a diet providing foods of a varied nature, in proportions such that foods rich in some nutrients do not limit intakes of foods rich in others.

1.2.1 A supply and demand model

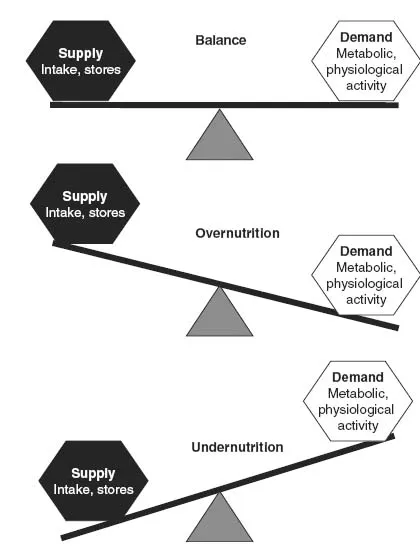

There is another way of viewing the meaning of balance or a balanced diet, whereby the relationship between nutrient intake and function is the main consideration. A diet that is in balance is one where the supply of nutrients is equal to the requirement of the body for those nutrients. Essentially, balance could be viewed as equivalent to an economic market, in which supply of goods or services needs to be sufficient to meet demands for those goods or services. Figure 1.1 summarizes the supply and demand model of nutritional balance.

Whether or not the diet is in balance will be a key determinant of the nutritional status of an individual. Nutritional status describes the state of a person’s health in relation to the nutrients in their diet and subsequently within their body. Good nutritional status would generally be associated with a dietary pattern that supplies nutrients at a level sufficient to meet requirements, without excessive storage. Poor nutritional status would generally (though not always) be associated with intakes that are insufficient to meet requirements.

The supply and demand model provides a useful framework for thinking about the relationship between diet and health. As shown in Figure 1.1, maintaining balance with respect to any given nutrient requires the supply of the nutrient to be equivalent to the overall demand for that nutrient. Demand comprises any physiological or metabolic process that utilizes the nutrient and may include use as an energy-releasing substrate, as an enzyme cofactor, as a structural component of tissues, a substrate for synthesis of macro-molecules, as a transport element, or as a component of cell–cell signaling apparatus. The supply side of the balance model comprises any means through which nutrients are made available to meet demand. This goes beyond delivery through food intake and includes stores of the nutrient that can be mobilized within the body, and quantities of the nutrient that might be synthesized de novo (e.g., vitamin D is synthesized in the skin through the action of sunlight).

1.2.2 Overnutrition

When supply does not match demand for a nutrient, then the system is out of balance and this may have important consequences in terms of health and disease. Overnutrition (Figure 1.1) will generally arise because the supply of a nutrient is excessive relative to demand. This is either because intake of foods containing that nutrient increases, because the individual consumes supplements of that nutrient, or because demand for that nutrient declines with no equivalent adjustment occurring within the diet. The latter scenario particularly applies to the elderly, for whom energy requirements fall due to declining physical activity levels and resting metabolic rate (Rivlin, 2007). Commonly, intakes of energy that were appropriate in earlier adulthood will be maintained, resulting in excessive energy intake.

Figure 1.1 The concept of balance. The demands for nutrients comprise metabolic and physiological processes that utilize nutrients. Supply is determined by intakes of food, availability of nutrient stores, and de novo production of nutrients.

The consequences of overnutrition are generally not widely considered in the context of health and disease, unless the nutrient concerned is directly toxic or harmful when stored in high quantities. The obvious example here is, again, energy, where overnutrition will result in fat storage and obesity. For many nutrients, overnutrition within reasonable limits has no adverse effect as the excess material will either be stored or excreted. At megadoses, however, most nutrients have some capacity to cause harm. Accidental consumption of iron supplements or iron overload associated with inherited disorders is a cause of disease and death in children. At high doses, iron will impair oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial function, leading to cellular damage in the liver, heart, lungs, and kidneys. Excess consumption of vitamin A has been linked to development of birth defects in the unborn fetus (Martinez-Frias and Salvador, 1990).

Overnutrition for one nutrient can also have effects upon nutritional status with respect to other nutrients, and can impact on physiological processes involving a broader range of nutrients. For example, regular consumption of iron supplements can impact upon absorption of other metals such as zinc and copper, by competing for gastrointestinal transporters and hence promote undernutrition with respect to those trace elements. Having an excess of a particular nutrient within the body can also promote undernutrition with respect to another by increasing the demand associated with processing the excess. For example, a diet rich in the amino acid methionine will tend to increase circulating and tissue concentrations of homocysteine. Processing of this damaging intermediate increases the demand for B vitamins, folic acid, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12, which are all involved in pathways that convert homocysteine to less harmful forms (Lonn et al., 2006).

1.2.3 Undernutrition

Undernutrition arises when the supply of nutrient fails to meet demand. This can occur if intakes are poor, or if demands are increased (Figure 1.1). In the short– medium term, low intakes are generally cushioned by the fact that the body has reserves of all nutrients that can be mobilized to meet demand. As such, for adults, it will usually require prolonged periods of low intake to have a significantly detrimental effect on nutritional status.

1.2.3.1 Increased demand

There are a number of situations that may arise to increase demand in such a way that undernutrition will arise if supply is not also increased accordingly. These include pregnancy, lactation, and trauma. Trauma encompasses a wide range of physical insults to the body, including infection, bone fracture, burns, surgery, and blood loss. Although diverse in nature, all of these physiological insults lead to the same metabolic response. This acute phase response (Table 1.1) is largely orchestrated by the cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1 (Grimble, 2001). Their net effect is to increase demand for protein and energy and yet paradoxically they have an anorectic effect. Thus, demand increases and supply will be impaired leading to protein–energy malnutrition. While in many developing countries, we associate protein–energy malnutrition with starvation in children, in developed countries such as the UK protein–energy malnutrition is most commonly noted in surgical patients and patients recovering from major injuries (Allison, 2005).

Table 1.1 The acute phase inflammatory response to trauma or infection

| Metabolic change | Catabolism of protein, muscle wastage. Amino acids converted to glucose for energy, or used to synthesize acute phase proteins. Catabolism of fat for energy |

| Fever | Body temperature rises to kill pathogens. Hypothalamic regulation of food intake disrupted, leading to loss of appetite |

| Hepatic protein synthesis | Acute phase proteins synthesized to combat infection (e.g., C-reactive protein, α1-proteinase inhibitor, and ceruloplasmin). Liver reduces synthesis of other proteins, including transferrin and albumin |

| Sequestration of trace elements | Zinc and iron taken up by tissues to remove free elements that may be utilized by pathogens |

| Immune cell activation | B cells produce increased amounts of immunoglobulins. T cells release cytokines to orchestrate the inflammatory response |

| Cytokine production | Tumor necrosis factor-α and the interleukins 1, 2, 6, 8, and 10 work to produce a hypermetabolic state that favors production of substrates for immune function, but inhibits reproduction and spread of pathogens |

1.2.3.2 The metabolic response to trauma

The human body is able to adapt rates of metabolism and the nature of metabolic processes to ensure survival in response to adverse circumstances. The metabolic response to adverse challenges will depend upon the nature of the challenge. Starvation leads to increased metabolic efficiency, which allows reserves of fat and protein to be utilized at a controlled rate that prolongs survival time and hence maximizes the chances of the starved individual regaining access to food. In contrast, the physiological response to trauma generates a hypermetabolic state in which reserves of fat and protein are rapidly mobilized in order to fend off infection and promote tissue repair (Table 1.1). Physiological stresses to the body, including infection, bone fracture, burns, or other tissue injury, elicit a common metabolic response regardless of their nature. Thus, a minor surgical procedure will produce the same pattern of metabolic response as a viral infection. It is the magnitude of the response that is variable and this is largely determined by the severity of the trauma (Romijn, 2000).

The hypermetabolic response to trauma is driven by endocrine changes that promote the catabolism of protein and fat reserves. Following the initial physiological insult, there is an increase in circulating concentrations of the catecholamines, cortisol, and glucagon. Increased cortisol and glucagon serve to stimulate rates of gluconeogenesis and hepatic glucose output, thereby maintaining high concentrations of plasma glucose. The breakdown of protein to amino acids provides gluconeogenic substrates and also leads to greatly increased losses of nitrogen via the urine. Lipolysis is stimulated and circulating free fatty acid concentrations rise dramatically. These are used as energy substrates, along with glucose.

The response to trauma is essentially an inflammatory process and, as such, the same metabolic drives are noted in individuals suffering from long-term inflammatory diseases including cancer and inflammatory bowel disease (Richardson and Davidson, 2003). The inflammatory response serves two basic functions. Firstly, it activates the immune system, raises body temperature, and repartitions micronutrients in order to create a hostile environment for invading pathogens (Table 1.1). Secondly, it allocates nutrients toward processes that will contribute to repair and healing.

The inflammatory response is orchestrated by the pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6) and the anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10). Whenever injury or infection occurs, the pro-inflammatory species are released by monocytes, macrophages, and T helper cells. The level of cytokines produced is closely related to the severity of the trauma (Lenz et al., 2007). The impact of pro-inflammatory cytokines is complex. On the one hand, they activate the immune system and protect the body from greater trauma. On the other, at the local level of any injury, they increase damage by stimulating the immune system to release damaging oxidants and other agents that indiscriminately destroy invading pathogens and the body’s own cells. The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines therefore has to be counterbalanced as an excessive response can lead to death (Grimble, 2001). This is the role of the anti-inflammatory cytokines and some of the acute phase response proteins, several of which inhibit the proteinases released during inflammation and therefore limit the breakdown of host tissues.

In addition to stimulating proteolysis and lipolysis within muscle and adipose tissue, the cytokines have a number of actions that impact upon nutritional status. Firstly, they increase the basal metabolic rate. An element of creating a hostile environment for pathogens includes raising the core temperature of the body (fever). This greatly increases energy demands. The capacity to meet those demands through feeding is reduced as cytokines also act upon the gut and the centers of the hypothalamus that regulate appetite, effectively switching off the desire to eat. As can be seen in Table 1.2, the increased metabolic rate associated with the response to trauma greatly increases the demands of the body for both energy and protein. In severe cases, requirements can be doubled, even though the critically ill patient will be immobilized and not expending energy through physical activity. This can pose major challenges for clinicians managing such cases as the injured patient maybe unable to feed normally, and due to the anorectic influences of pro-inflammatory cytokines, the capacity to ingest sufficient energy, protein, and other nutrients...