eBook - ePub

Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth

About this book

Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth encompasses the full scope of acute dental trauma, including all aspects of inter-disciplinary treatment. This fourth edition captures the significant advances which have been made in the subject of dental traumatology, since the publication of the last edition more than a decade ago. The comprehensive nature of the book is designed to appeal to distinguished clinicians and scholars of dental traumatology, whether they be oral surgeons, pediatric dentists, endodontists, or from a related specialist community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth by Jens O. Andreasen, Frances M. Andreasen, Lars Andersson, Jens O. Andreasen,Frances M. Andreasen,Lars Andersson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Oral Health & Surgery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Wound Healing Subsequent to Injury

F. Gottrup

Definition

The generally accepted definition of wound healing is: ‘a reaction of any multicellular organism on tissue damage in order to restore the continuity and function of the tissue or organ’. This is a functional definition saying little about the process itself and which factors are influential.

Traumatic dental injuries usually imply wound healing processes in the periodontium, the pulp and sometimes associated soft tissue. The outcome of these determines the final healing result (Fig. 1.1). The general response of soft and mineralized tissues to surgical and traumatic injuries is a sensitive process, where even minor changes in the treatment procedure may have an impact upon the rate and quality of healing.

In order to design suitable treatment procedures for a traumatized dentition, it is necessary to consider the cellular and humoral elements in wound healing. In this respect considerable progress has been made in understanding of the role of different cells involved.

In this chapter the general response of soft tissues to injury is described, as well as the various factors influencing the wound healing processes. For progress to be made in the treatment of traumatic dental injuries it is necessary to begin with general wound healing principles. The aim of the present chapter is to give a general survey of wound healing as it appears from recent research. For more detailed information about the various topics the reader should consult textbooks and review articles devoted to wound healing (1–23, 607–612).

Nature of a traumatic injury

Whenever injury disrupts tissue, a sequence of events is initiated whose ultimate goal is to heal the damaged tissue. The sequence of events after wounding is: control of bleeding; establishing a line of defense against infection; cleansing the wound site of necrotic tissue elements, bacteria or foreign bodies; closing the wound gap with newly formed connective tissue and epithelium; and finally modifying the primary wound tissue to a more functionally suitable tissue.

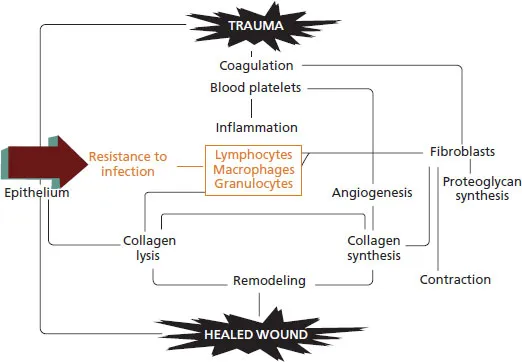

This healing process is basically the same in all tissues, but may vary clinically according to the tissues involved. Thus wound healing after dental trauma is complicated by the multiplicity of cellular systems involved (Fig. 1.2).

During the last two decades, significant advances have been made in the understanding of the biology behind wound healing in general and new details concerning the regulating mechanisms have been discovered.

While a vast body of knowledge exists concerning the healing of cutaneous wounds, relatively sparse information exists concerning healing of oral mucosa and odontogenic tissues. This chapter describes the general features of wound healing, and the present knowledge of the cellular systems involved. Wound healing as it applies to the specific odontogenic tissues will be described in Chapter 2.

Wound healing biology

Wound healing is a dynamic, interactive process involving cells and extracelluar matrix and is dependent on internal as well as external factors. Different schemes have been used in order to summarize the wound healing process. With increasing knowledge of the involved processes, cell types etc., a complete survey of all aspects will be hugely difficult to overview. The authors have for many years used a modification of the original Hunt flow diagram for wound healing (19) (Fig 1.2). This diagram illustrates the main events in superficial epithelialization and production of granulation tissue.

The wound healing process will be described in detail in the following section.

Fig. 1.1 Cells involved in the healing event after a tooth luxation. Clockwise from top: endothelial cell and pericytes; thrombocyte (platelet); erythrocyte; fibroblast; epithelial cell; macrophage; neutrophil; lymphocytes; mast cell.

Fig. 1.2 Modified Hunt flow diagram for wound healing.

Repair versus regeneration

The goal of the wound healing process after injury is to restore the continuity between wound edges and to re-establish tissue function. In relation to wound healing, it is appropriate to define various terms, such as repair and regeneration. In this context, it has been suggested that the term regeneration should be used for a biologic process by which the structure and function of the disrupted or lost tissue is completely restored, whereas repair or scar formation is a biologic process whereby the continuity of the disrupted or lost tissue is regained by new tissue which does not restore structure and function (14). Throughout the text, these terms will be used according to the above definitions. The implication of repair and regeneration as they relate to oral tissues is discussed in Chapter 2.

Cell differentiation

Cell differentiation is a process whereby an embryonic nonfunctional cell matures and changes into a tissue-specific cell, performing one or more functions characteristic of that cell population. Examples of this are the mesenchymal paravascular cells in the periodontal ligament and the pulp, and the basal cells of the epithelium. A problem arises as to whether already functioning odontogenic cells can revert to a more primitive cell type. Although this is known to take place in cutaneous wounds, it is unsettled with respect to dental tissues (see Chapter 2). With regard to cell differentiation, it appears that extracellular matrix compounds, such as proteoglycans, have a significant influence on cell differentiation in wound healing (25).

Progenitor cells (stem cells)

Among the various cell populations in oral and other tissues, a small fraction are progenitor cells. These cells are self-perpetuating, nonspecialized cells, which are the source of new differentiating cells during normal tissue turnover and healing after injury (17–19). The role of these in wound healing is further discussed in Chapter 3.

Cell cycle

Prior to mitosis, DNA must duplicate and RNA be synthesized. Since materials needed for cell division occupy more than half the cell, a cell that is performing functional synthesis (e.g. a fibroblast producing collagen, an odontoblast producing dentin or an epithelial cell producing keratin) does not have the resources to undergo mitosis. Conversely, a cell preparing for or undergoing mitosis has insufficient resources to undertake its functions. This may explain why it is usually the least differentiated cells that undergo proliferation in a damaged tissue, and why differentiated cells do not often divide (15).

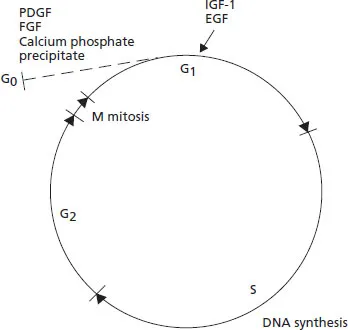

The interval between consecutive mitoses has been termed the cell cycle which represents an ordered sequence of events that are necessary before the next mitosis (Fig. 1.3): The cell cycle has been subdivided into phases such as G1, the time before the onset of DNA synthesis. In the S phase the DNA content is replicated, G2 is the time between the S phase and mitosis, and M the time of mitosis (Fig. 1.3). The cumulative length of S, G2 and M is relatively constant at 10–12 hours, whereas differences occur among cell types in the duration of G1 (26).

Cells that have become growth arrested enter a resting phase, G0, which lies outside the cell cycle. The G0 state is reversible and cells can remain viable in G0 for extended periods.

In vivo, cells can be classified as continuously dividing (e.g. epithelial cells, fibroblasts), non-dividing post-mitotic (e.g. ameloblasts) and cells reversibly growth arrested in G0 that can be induced to re-enter the proliferative cycle.

Fig. 1.3 Cell cycle. G0 = resting phase; G1 = time before onset of DNA synthesis; S = replication of DNA; G2 = time between DNA replication and mitosis; M = mitosis.

Factors leading to fibroblast proliferation have been studied in the fibroblast system. Resting cells are made competent to proliferate (i.e. entry of G0 cells into early G1 stage) by so-called competence factors (i.e. platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and calcium phosphate precipitates). However, there is no progression beyond G1 until the appearance of progression factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), epidermal growth factor (EGF) and other plasma factors (26) (Fig. 1.3).

Cell migration

Optimal wound repair is dependent upon an orderly influx of cells into the wound area. Directed cell motion requires polarization of cells and formation of both a leading edge that attaches to the matrix and a trailing edge that is pulled along. The stimulus for directional cell migration can be a soluble attractant (chemotaxis), a substratum-bound gradient of a particular matrix constituent (haptotaxis) or the three-dimensional array of extracellular matrix within the tissue (contact guidance). Finally there is a free edge effect which occurs in epithelial wound healing (see p. 36) (27, 28).

Typical examples of cells responding to chemotaxis are circulating neutrophils and monocytes and macrophages (see p. 23). The chemoattractant is regulated by diffusion of the attractant from its source into an attraction-poor medium.

Cells migrating by haptotaxis extend lamellipodia more or less randomly and each of these protruding lamellipodia competes for a matrix component to adhere to, whereby a leading edge will be created on one side of the cell and a new membrane inserted into the leading edge. In that context, fibronectin and laminin seem to be important for adhesion (27).

Contact guidance occurs as the cell is forced along paths of least resistance through the extracellular matrix. Thus, migrating cells align themselves according to the matrix configuration, a phenomenon that can be seen in the extended fibrin strands in retracting blood clots (see p. 9), as well as in the orientation of fibroblasts in granulation tissue (29). In this context it should be mentioned that mechanisms also exist whereby spaces are opened within the extracellular area when cells migrate. Thus both fibroblasts and macrophages use enzymes such as plasmin, plasminogen and collagenases for this purpose (30).

During wound repair, a given parenchymal cell may migrate into the wound space by multiple mechanisms occurring concurrently or in succession. Factors related to cell migration in wound healing are described later for each particular cell type.

Dynamics of wound repair

Classically the events taking place after wounding can be divided into three phases, namely the inflammation, the proliferation and the remodeling phases (5, 13, 20–23, 31). The inflammation phase may, however, be subdivided into a hemostasis phase and an inflammatory phase. But, it should be remembered that wound healing is a continuous process where the beginning and end of each phase cannot be clearly determined and phases do overlap.

Tissue injury causes disruption of blood vessels and extravasation of blood constituents. Vasoconstriction provides a rapid, but transient, decrease in bleeding. The extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation pathways are also immediately activated. The blood clots together with vasoconstriction re-establish hemostasis and provide a provisional extracellular matrix for cell migration. Adherent platelets undergo morphological changes to facilitate formation of the hemostatic plug and secrete several mediators of wound healing such as platelet derived growth factor, which attract and activate macrophages and fibroblasts. Other growth factors and a great number of other mediators such as chemoattractants and vasoactive substances are also released. The released products soon initiate the inflammatory response.

Inflammation phase

Following the initial vasoconstriction a vasodilatation takes place in the wound area. This supports the migration of inflammatory cells into the wound area (Fig. 1.4).

T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Wound Healing Subsequent to Injury

- 2 Response of Oral Tissues to Trauma

- 3 Stem Cells and Regeneration of Injured Dental Tissue

- 4 Osteoclastic Activity

- 5 Physical and Chemical Methods to Optimize Pulpal and Periodontal Healing After Traumatic Injuries

- 6 Socio-Psychological Aspects of Traumatic Dental Injuries

- 7 Child Physical Abuse

- 8 Classification, Epidemiology and Etiology 217

- 9 Examination and Diagnosis of Dental Injuries

- 10 Crown Fractures

- 11 Crown-Root Fractures

- 12 Root Fractures

- 13 Luxation Injuries of Permanent Teeth: General Findings

- 14 Concussion and Subluxation

- 15 Extrusive Luxation and Lateral Luxation 411

- 16 Intrusive Luxation

- 17 Avulsions

- 18 Injuries to the Supporting Bone

- 19 Injuries to the Primary Dentition

- 20 Injuries to Developing Teeth

- 21 Soft Tissue Injuries

- 22 Endodontic Management and the Use of Calcium Hydroxide in Traumatized Permanent Teeth

- 23 New Endodontic Procedures using Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA) for Teeth with Traumatic Injuries

- 24 Orthodontic Management of the Traumatized Dentition

- 25 Restoration of Traumatized Teeth with Resin Composites

- 26 Resin-related Bridges and Conventional Bridges in the Anterior Region

- 27 Autotransplantation of Teeth to the Anterior Region

- 28 Implants in the Anterior Region

- 29 Esthetic Considerations in Restoring the Traumatized Dentition: a Biologic Approach

- 30 Prevention of Dental and Oral Injuries

- 31 Prognosis of Traumatic Dental Injuries: Statistical Considerations

- 32 Splinting of Traumatized Teeth

- 33 Bleaching of the Discolored Traumatized Tooth

- 34 Economic Aspects of Traumatic Dental Injuries

- 35 Information to the Public, Patients and Emergency Services on Traumatic Dental Injuries

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Appendix 4

- Index