![]()

1

Definitions and Epidemiology

Epilepsy is – rather like headache – a symptom of neurological dysfunction. It has many forms and underlying causes, and also biological and non-biological facets that extend well beyond the simple occurrence of seizures. Treatment approaches vary considerably in the different types of epilepsy and, in this section of the book, the various clinical forms and causes of epilepsy are described.

The forms of epilepsy can be described and classified in four main ways: (1) by seizure type; (2) in the case of partial (focal) seizures, by the anatomical site of seizure onset; (3) by syndrome; and (4) by aetiology. Each system has its value. In Chapter 2 the seizure type and anatomical substrate are described, in Chapter 3 the epilepsy syndromes and in Chapter 4 the causes of epilepsy.

What is not available, given our current state of knowledge, is a description, or classification, of the types of epilepsy according to molecular mechanisms. Such a ‘pathophysiological’ classification would be highly desirable and is the challenge for the future.

Definitions

Epileptic seizure (epileptic fit)

Epileptic seizures are defined as ‘the transient clinical manifestations that result from an episode of epileptic neuronal activity’. The epileptic neuronal activity is a specific dysfunction, characterized by abnormal synchronization, excessive excitation and/or inadequate inhibition, and can affect small or large neuronal populations (aggregates). The clinical manifestations are sudden, transient and usually brief. They include motor, psychic, autonomic and sensory phenomena, with or without alteration in consciousness or awareness. The symptoms depend on the part of the brain involved in the epileptic neuronal discharge, and the intensity of the discharge. The signs of a seizure vary from the only too evident wild manifestations of a generalized convulsion, to the subtle changes, apparent only to the patient, of some simple partial seizures. Some neuronal epileptic discharges, detectable by electroencephalography, are not accompanied by any evident symptoms or signs and this complicates definition. For most purposes these ‘subclinical’ or ‘interictal’ changes are not considered to be epileptic seizures, although the physiological changes can be identical to overt attacks, and the difference is largely one of degree. Furthermore, subtle impairment of psychomotor performance can be demonstrated due, for example, to interictal spiking, of which the patient may be unaware.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is ‘a disorder of brain characterized by an ongoing liability to recurrent epileptic seizures’. This definition is unsatisfactory for various reasons. First, it is difficult clearly to define, in many cases, to what extent recurrent attacks are likely – a definition based on crystal-ball gazing is inherently unsatisfactory. In the clinical setting, for pragmatic reasons, a ‘liability to further attacks’ is often said to be present when two or more spontaneous attacks have occurred, on the basis that this means that more are likely. However, this arbitrary definition is inadequate, for example, in patients after a single attack who have a clear liability to further seizures, for patients who have had more than one provoked attack (see below), or for those whose epilepsy has remitted and whose liability for further attacks has lapsed. Furthermore, in physiological terms, the distinction between single and recurrent attacks is often meaningless. A second problem is that ‘epilepsy’ occurs with a wide variety of cerebral pathologies; similar to ‘anaemia’ or ‘headache’ it is a symptom masquerading as a disease.

The standard definition is also inadequate in epileptic states in which physiological changes occur without obvious seizures. In these so-called epileptic encephalopathies, alterations in cognition and other cortical functions are major features unrelated to overt seizures (examples include the Landau–Kleffner syndrome and the childhood epileptic encephalopathies). Patients with subclinical discharges sometimes exhibit cognitive, psychological or behavioural change. There are also certain non-epileptic conditions where differentiation from epilepsy is problematic. These are sometimes called borderline conditions, and include certain psychiatric conditions, some cases of migraine and some forms of movement disorder. Finally, the fact of ‘having epilepsy’ involves far more than the risk of recurrent seizures, but incorporates prejudice and stigmatization, and psychosocial and developmental issues that may, indeed, be more problematic than the seizures themselves. A comprehensive definition should ideally incorporate these broader psychosocial, developmental and cognitive aspects

There are furthermore types of overt epileptic seizure that do not warrant a diagnosis of epilepsy. These include isolated first seizures in which no liability to recurrence can be demonstrated, some provoked seizures, febrile seizures, and the ‘early seizures’ after acute brain injury.

Epilepsy syndrome

An epileptic syndrome is defined as ‘an epileptic disorder characterized by a cluster of signs and symptoms customarily occurring together’ (see chapter 3). Different syndromes have different prognoses and require different treatment approaches. They are commonly diagnosed in children (and indeed up to 70% of childhood epilepsy may be categorized into epilepsy syndromes) but more rarely so in adult epilepsy.

Status epilepticus

This is defined as a condition in which epileptic seizures continue, or are repeated without recovery, for a period of 30 minutes or more. This is the maximal expression of epilepsy, and often requires emergency therapy (see chapter 9). There are physiological and neurochemical changes that distinguish status epilepticus from ordinary epileptic seizures. Recent debate has revolved around the minimum duration of seizures necessary to define this condition, with suggestions ranging from 10 min to 60 min; the usual 30 min is to some extent a compromise. As with the definitions of epilepsy and of epileptic seizures, there is a range of boundary conditions associated with status epilepticus that do not fall easily into the simple clinical definitions.

Febrile seizures

A febrile seizure is an epileptic attack occurring in children age under 5 years (usually between 2 and 5 years) in the setting of a rise in body temperature. For most purposes, such seizures are not included within the rubric of ‘epilepsy’, because they are very common (2–5% of children in the west have at least one febrile seizure, and 9% in Japan), presumably have a specific physiological basis that is distinct from epilepsy, and have clinical implications that are very different from those of epilepsy. Febrile seizures are discussed further on pp. 28–30.

Epileptic encephalopathy

An ‘epileptic encephalopathy’ is a term used to describe a clinical state in which epilepsy is a prominent feature, and in which changes in cognition or other cerebral functions are, at least in part, likely to be due to ongoing epileptic processes in the brain. The epileptic encephalopathies are more common in children than in adults.

Idiopathic, symptomatic, provoked and cryptogenic epilepsy

Epilepsy can have many causes. These are terms used to describe the causes of epilepsy and are dealt with in more detail later (see chapter 3).

Active epilepsy and epilepsy in remission

A person is said to have active epilepsy when at least one epileptic seizure has occurred in the preceding period (usually 2–5 years). Conversely, epilepsy is said to be in remission when no seizures have occurred in this preceding period. The period of time used in these definitions varies in different studies, and furthermore some definitions of remission require the patient not only to be seizure free but also off medication. An interesting question, and one of great importance to those with epilepsy, is after what period of remission can the person claim no longer to have the condition? Logically, the condition has remitted as soon as the last seizure has occurred, but this cannot be known except retrospectively. In practice, it is reasonable to consider epilepsy to have ceased in someone off therapy if 2–5 years have passed since the last attack.

Acute symptomatic, remote symptomatic and congenital epilepsy

A categorization of epilepsy has been used for epidemiological studies that divided epilepsy into three types: acute symptomatic epilepsy, where there is an acute cause; remote symptomatic, where there is a cause that has been present for at least 3 months; and idiopathic, where the cause is not known. This classification has been severely criticized and is, in the view of the author, of little value and should not now be used.

Frequency and population features of epilepsy

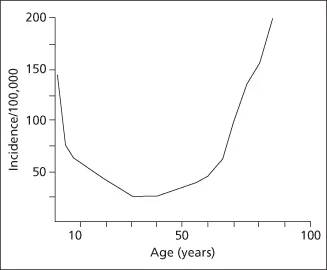

Epilepsy is a common condition. Its incidence is in the region of 80 cases per 100 000 persons per year, with different studies showing rates varying between 50 and 120 per 100 000 per year. Its point prevalence is about 4–10 cases per 1000 persons. The prevalence is higher in developing countries, perhaps due to poorer perinatal care and standards of nutrition and public hygiene, and the greater risk of brain injury, cerebral infection and congenital/developmental disorders The frequency of epilepsy is also slightly higher in lower socioeconomic classes. However, more striking than any differences in frequency is the fact that epilepsy occurs in all parts of the world and can affect all strata in a population. Males may be slightly more likely to develop epilepsy than females, and there are no differences in rate in large ethnic populations. The incidence of seizures is age dependent, with the highest rates in the first year of life and a second peak in late life (Figure 1.1). About 40% of patients develop epilepsy below the age of 16 years and about 20% over the age of 65 years. In recent times, the rate in children has been falling, possibly owing to better public health and living standards and better perinatal care. Conversely, the rate in elderly people is rising largely due to cerebrovascular disease.

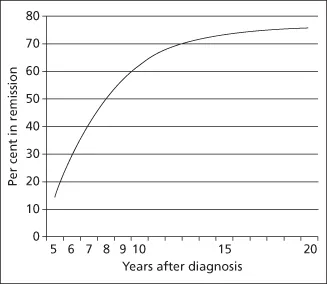

An isolated (first and only) seizure occurs in about 20 people per 100 000 each year. The cumulative incidence of epilepsy – the risk of an individual developing epilepsy in his or her lifetime – is between 3 and 5%. The fact that prevalence is much lower than cumulative incidence demonstrates that in many cases epilepsy remits. In fact the prognosis is generally good and, within 5 years of the onset of seizures, 50–60% of patients will have entered long remission (Figure 1.2). However, in about 20% of cases, epilepsy, once developed, never remits. Fertility rates are reduced by about 30% in women with epilepsy (see pp. 136–137).

Mortality of epilepsy

Standardized mortality rates are also two to three times higher in patients with epilepsy than in others in the population. The excess mortality is due largely to the underlying cause of the epilepsy. However, some deaths are directly related to seizures and there are higher rates of accidents, sudden unexpected deaths and suicides among patients with epilepsy when compared with the general population. The rates of death are highest in the first few years after diagnosis, reflecting the underlying cerebral di...