![]()

Chapter 1

The Nature of the Beast

Setting the Scene

Adams School on Chicago’s South Side is something of a success story. Serving students from homes well below the poverty line, Adams was in crisis in the late 1980s; only 16 percent of its students scored at or above national norms on standardized tests in reading. A decade later, administrators, teachers, and students at Adams had reason to celebrate. Students had made impressive gains on achievement tests, and attendance rates had improved considerably. Adams had developed a reputation as a success and as a place where teachers wanted to work.

As teachers and administrators at Adams tell the story, things began to change in 1988 when Brenda Williams took over the position of school principal. An assistant principal vividly recalled, “I could remember the very first day that she came in and we had a meeting . . . and it was a meeting that set forth her goal to come here and to make sure that academically we were growing . . . and she set before us the challenge that we have.” Williams, an energetic African American woman, worked diligently during the 1990s to improve teaching and learning at Adams School. In local commentators’, scholars’, and teachers’ telling of the Adams story, Williams gets much of the credit.

The Lure of Leaders in the “Heroics of Leadership” Genre

The Adams story will ring true for consumers of education literature the world over. It is a familiar tale: a charismatic principal takes the helm in a failing school, setting new expectations for students and staff alike and establishing new organizational routines and structures in an effort to make over the school culture. Over time, the principal’s actions contribute to greater teacher satisfaction, higher and shared expectations for student learning among staff, and improved student achievement. Evidence of success begins to accumulate as teachers report greater job satisfaction and higher expectations for student learning.

Deservedly, principals like Williams become the stars of the education world, and their heroic acts become blueprints for “successful” school leadership. The success of these heroes and heroines becomes the subject of academic publications, popular media accounts, education folklore, and even an occasional documentary or movie. In the “heroics of leadership” genre, or the “heroic leader paradigm” (Yukl, 1999, p. 292), charismatic leaders and their gallant acts are center stage; everyone and everything else are at best cast in minor, supporting roles. Even when others are cast in prominent roles, the focus is on the heroic actions of each individual, and by adding together their individual efforts, one gets an account of leadership. Letting go of the myth of individualism is difficult even when leadership tales venture beyond the single hero or heroine to acknowledge the part played by two or more supporting players.

A Distributed Perspective on Leadership: Essential Elements

In this book, I develop a distributed perspective on leadership as an alternative to accounts that equate leadership with the gallant acts of one or more leaders in an organization. My question is this: What does it mean to take a distributed perspective on school leadership? A distributed leadership perspective moves beyond the Superman and Wonder Woman view of school leadership. It is about more than accounting for all the leaders in a school and counting up their various actions to arrive at some more comprehensive account of leadership. Moving beyond the principal or head teacher to include other potential leaders is just the tip of the iceberg, from a distributed perspective.

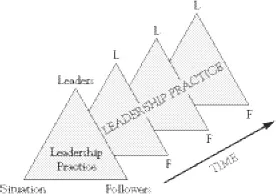

A distributed perspective is first and foremost about leadership practice (see Figure 1.1). This practice is framed in a very particular way, as a product of the joint interactions of school leaders, followers, and aspects of their situation such as tools and routines. This distributed view of leadership shifts focus from school principals like Brenda Williams and other formal and informal leaders to the web of leaders, followers, and their situations that gives form to leadership practice.

Distributed leadership means more than shared leadership. Too frequently, discussions of distributed leadership end prematurely with an acknowledgment that multiple individuals take responsibility for leadership: that there is a leader plus other leaders at work in the school. Though essential, this leader-plus aspect is not sufficient to capture the complexity of the practice of leadership. From a distributed perspective, it is the collective interactions among leaders, followers, and their situation that are paramount. The situation of leadership isn’t just the context within which leadership practice unfolds; it is a defining element of leadership practice. Aspects of a situation—such as the Breakfast Club or the Five-Week Assessment routine at Adams School or a tool like student test data—don’t simply affect or influence what school leaders do, enabling them to practice more or less effectively. These routines and tools are also produced by leadership practice. They mutually constitute leadership practice in interaction with leaders and followers.

In a distributed perspective on leadership, three elements are essential:

- Leadership practice is the central and anchoring concern.

- Leadership practice is generated in the interactions of leaders, followers, and their situation; each element is essential for leadership practice.

- The situation both defines leadership practice and is defined through leadership practice.

From a distributed perspective, leadership involves mortals as well as heroes. It involves the many and not just the few. It is about leadership practice, not simply roles and positions. And leadership practice is about interactions, not just the actions of heroes.

Problems with the Heroics of Leadership

The heroics of leadership genre is problematic for four reasons. First, heroic epics typically equate school leadership with school principals and their valiant actions. While other leaders are sometimes featured in these accounts, they are usually cast in minor, supporting roles. Vital though the school principal is, school leadership does not begin and end with the person in the principal’s office.

Second, most accounts of school leadership pay scant attention to the practice of leadership (Hallinger and Heck, 1996). They dwell mostly on people, structures, functions, routines, and roles. And they focus on the “what” rather than the “how” of leadership, shortchanging how leadership gets done through the ordinary, everyday practices involved in leadership routines and functions. While knowing what leaders do is important, knowing how they do it is also essential in understanding the practice of leadership. For example, recent scholarship implies that school leaders cultivate collaborative culture among teachers (an organizational function that is thought to be critical for school improvement) by setting tasks that involve teachers’ working together (Goldring and Rallis, 1993; Liberman, Falk, and Alexander, 1994; Louis, Marks, and Kruse, 1996). Understanding how leadership practice creates these tasks in the day-to-day work of schools is as important as understanding what strategies help address which functions.

Third, when leadership practice does make it onto the radar screen, it is depicted mostly in terms of the actions, great or otherwise, of one or more leaders. Concentrating on individual actions fails to capture the significance of interactions.

Fourth, in the heroic leadership tradition, leadership is defined chiefly in terms of its outcome. This is problematic because leadership can occur without evidence of its outcome.

Fixating on the Heroic Leader

In many accounts of school leadership, the heroic leadership genre persists, with the school principal or head teacher as the protagonist, sometimes accompanied by assistant principals and others in formal leadership positions. Describing improvements at Adams School in this way is problematic because Brenda Williams did not turn the school around single-handedly. An array of other individuals—other administrators, specialists, and classroom teachers—with tools and routines of various hues were also critical in Adams makeover.

Williams is no slouch; she deserves to be the central character in the story of Adams’s transformation. Yet, as in any good epic, what she did and how she did it depended in good measure on many others, who, by virtue of their formal roles or informal responsibilities, helped lead improvement efforts. Williams acknowledged the crucial role of others when she said, “I just couldn’t do it all.” She explained that she had put in place a group of leaders to help her transform Adams School. She reported, for example, that hiring an assistant to handle student disciplinary matters was critical: “I couldn’t get involved in that day-to-day discipline and focus in on the instruction program too.” A teacher at Adams also points to the importance of others in leading the transformation, remarking, “Starting with Dr. Williams . . . we have a very good team here. If they weren’t who they are, we wouldn’t be who we are. If the administration had not set the tone, we would not have adopted this tone.” It was a team of people, albeit with Williams at the helm, that was critical in Adams School’s transformation. Other administrators and classroom teachers took pivotal roles in leading efforts to improve instruction, transform school culture, and change the expectations that staff had for students. Some of these individuals simply did what they were told when Williams delegated responsibilities to them. Others rose to the occasion afforded by a new organizational culture and new organizational arrangements at Adams and took on leadership responsibilities. While Williams figures prominently in any account of leadership at Adams, she doesn’t figure alone. Acknowledging that leadership practice extends beyond the school principal in no way undermines the vital role of the principal in school leadership but instead shows that leadership is often a collective rather than individualistic endeavor.

This first problem with the heroic leadership genre is addressed relatively easily by attending to the work of multiple leaders. I refer to this strategy as a leader-plus approach.

At Adams, for example, over a ten-year period, Williams and her staff worked on various organizational functions: constructing an instructional vision, developing teacher knowledge, procuring resources, and building a professional community. Further, Williams and her staff also constructed and institutionalized at Adams a number of leadership routines and structures in order to execute key organizational functions. These routines and structures included the School Improvement Planning Process, the Breakfast Club, and the Five-Week Assessment process. The Breakfast Club routine, a monthly meeting of teachers designed by school leaders to provide opportunities for teacher professional development, evolved over time as an opportunity to build professional community among teachers. A leader-plus approach recognizes that such routines and structures play an integral role in leadership.

Inattention to Leadership Practice

A few years ago, when I was describing leadership functions and arguing their importance for school improvement to a school principal, the principal retorted, “I know all that. Tell me how!” Understanding how leadership actually gets done in schools is imperative if research is to generate usable knowledge for school leaders. Describing the “what” is necessary but not sufficient to capture leadership practice.

Accounts of leadership often dwell exclusively on the structures and roles that schools should put in place and the leadership functions that need attention. The result is that day-to-day practice falls through the cracks. Studying the “how” as well as the “what” of leadership is essential.

An Incomplete Conception of Practice

Leadership practice is often equated with the actions of individuals. Practice writ large is thought about mostly in terms of the actions of the individual doing the practice. Hence, good or not-so-good practice is attributed almost entirely to the knowledge and skill of the individual practitioner. The elegance of the armoire is put down to the carpenter’s skill and experience; the carpenter’s tools rarely figure in the equation. But any skilled carpenter will tell you that the tools make a lot of difference in putting the armoire together. When it comes to practices of human improvement—teaching, leadership, psychotherapy—the situations are even more complex because practitioners often work in collectives and more often than not depend on their clients—students, followers, patients—to accomplish a task or implement some vision or goal. Hence, the practice of constructing and selling a vision for instructional improvement in a school cannot be understood by focusing solely on the actions of the school principal. For example, the practice of building and selling a new vision for instruction at Adams School had to do with more than the actions of Williams; this practice unfolded in the interactions among Williams and other leaders—assistant principals, literacy coordinators, teacher leaders—and in the interactions between leaders and followers. Further, the practice was enabled and constrained by an array of committees, routines, and tools, including student assessment instruments, regular staff get-togethers, and scheduling arrangements. These aspects of the situation often are ignored in attempts to account for leadership practice that fixate on the individual who is thought to be doing the practice. When tools and other aspects of the situation do figure in, they are seen as accessories to practice rather than essential, defining elements of it. Thinking about leadership in terms of interactions rather than actions offers a distinctly different perspective on leadership practice. Actions are still important, but they must be understood as part of interactions.

A Normative Definition of Leadership

One can point to Williams as a case of leadership because there is evidence that what she did influenced teachers’ motivation, knowledge, and behavior, which in turn contributed to improvement in student outcomes at Adams School. Defining leadership like this is problematic because the existence of leadership is only acknowledged when there is evidence of its effects or effectiveness.

By way of illustration, consider Kosten School on Chicago’s Northwest Side. At Kosten, a new principal and assistant principal worked to initiate routines designed to transform business as usual at the school, where teachers basically closed their doors and taught as they saw fit, with no oversight. The principal’s and assistant principal’s efforts to lead improvement in classroom instruction included regular reviews of teachers’ grade books, monitoring of classroom instruction, and attention to following lesson plans. For some teachers, these efforts didn’t influence their knowledge, motivation, or practice. But the motivation and practice of some teachers at Kosten were influenced by these collective endeavors, even if the effect was not universal. Even those teachers who openly resisted the improvement efforts understood them as leadership—practices designed to influence their work practices. Thus, relying on leadership outcomes—in particular, positive leadership outcomes—to infer the existence of leadership is problematic.

Defining leadership by relying on evidence of its outcomes or effects is not satisfactory because such definitions concentrate on a subset of what is considered to be leadership in organizations. Moreover, when leadership is defined chiefly in terms of its outcomes, efforts to study relationships between leadership and the effects of leadership end up as circular arguments. The distributed perspective addresses these shortcomings of the heroic leadership genre.

Prescription or Perspective?

Distributed leadership is frequently talked about as a cure-all for schools, a way that leadership ought to be carried out. But a distributed perspective on leadership should first be just that—a perspective or lens for thinking about leadership before rushing to normative action. In this view, distributed leadership is not a blueprint for doing school leadership more effectively. It is a way to generate insights into how leadership can be practiced more or less effectively.

A distributed perspective on leadership is best thought of as a framework for thinking about and analyzing leadership. It’s a tool for helping us think about leadership in new and unfamiliar ways. It can be used as a frame to help researchers decide what to look at when they investigate leadership. A distributed perspective can be used as a diagnostic instrument that draws practitioners’ and interventionists’ attention to hidden dimensions of school leadership and helps practitioners approach their work in new ways. And it can be a way to acknowledge and perhaps even celebrate the many kinds of unglamorous and unheroic leadership that often go unnoticed in schools...