- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

History of Cognitive Neuroscience

About this book

History of Cognitive Neuroscience documents the major neuroscientific experiments and theories over the last century and a half in the domain of cognitive neuroscience, and evaluates the cogency of the conclusions that have been drawn from them.

- Provides a companion work to the highly acclaimed Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience - combining scientific detail with philosophical insights

- Views the evolution of brain science through the lens of its principal figures and experiments

- Addresses philosophical criticism of Bennett and Hacker's previous book

- Accompanied by more than 100 illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access History of Cognitive Neuroscience by M. R. Bennett,P. M. S. Hacker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Neuroscience. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Perceptions, Sensations and Cortical Function: Helmholtz to Singer

1.1 Visual Illusions and their Interpretation by Cognitive Scientists

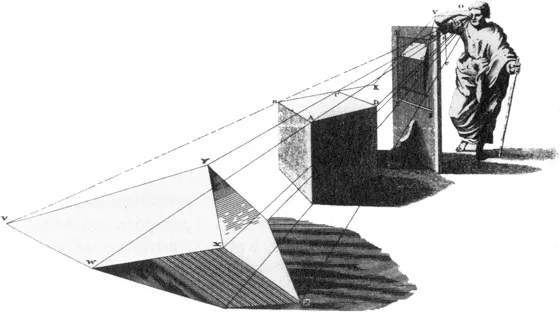

Helmholtz (fig. 1.1), in his Treatise on Physiological Optics, suggested that the formation of a perception involves the development of an unconscious hypothesis based on inductive inferences gained from sensations. For him perceptions are conclusions of unconscious inferences the premisses of which are unconscious and (more or less) indescribable sensations and (unconscious) generalizations about the correlation between past sensations and objects perceived. The viewer shown in fig. 1.2 takes the strangely shaped object in the foreground, looked at with one eye, to be a cube because it has all the identifiable features along the line of sight that a cube has. On Helmholtz’s hypothesis inductive inferences are made by the person in fig. 1.2 on the basis of the sensations due to the rays of light from the object, and these support the most likely hypothesis: namely, the perception of a cube.

Fig. 1.1. Helmholtz. Sketch by Franz von Lenbach (1894).

Courtesy of the Siemens-Forum, Munich.

Fig. 1.2. Drawing to illustrate Helmholtz’s argument on how a perception is formed. (Glynn, 1999, p. 197.)

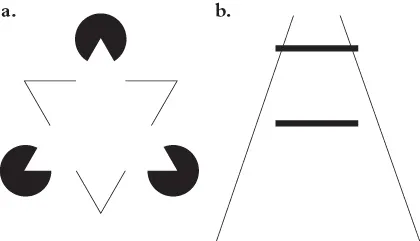

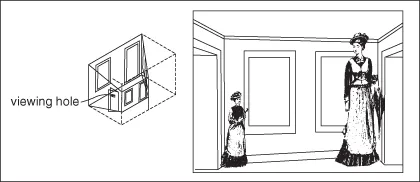

A variety of illusions (e.g. The Ponzo illusion, Kanizsa’s illusion, the Ames Room illusion) have been taken as explicable in terms of Helmholtz’s theory (Glynn, 1999). That is, these illusions can be explained by reference to the brain’s drawing inferences from its past experience to form hypotheses about the objects of its present experience. In the Kanizsa illusion (fig. 1.3a) a ghostly white triangle emerges as a consequence of our inferring that this is the obvious way of interpreting the missing sectors in the three black discs and the edges of the black triangle. In the Ponzo illusion (fig. 1.3b) the upper horizontal bar looks longer than the lower one because the near vertical converging lines are interpreted as railway tracks with parallel lines receding into the distance. Another example of this alleged process of inductive inference is provided by the Adelbert Ames distorting room which produces the experience of extraordinary variations in size of people placed at different positions in the room (fig. 1.4). This room is constructed so that when it is viewed through an eyehole with one eye, an image is produced on the retina identical with that of a rectangular room of uniform height, whereas actually the far wall recedes and both the floor and the ceiling slope, as shown in the small diagram. When people are placed in the far corners of the room, their size is judged in relation to the dimensions of the room on the assumption that this is rectangular. Yet another example which is taken to support Helmholtz’s hypothesis is provided by the Ramachandran photograph of fig. 1.5. This shows bumps and hollows that reverse on inversion of the photo. Whether it is interpreted as bumps or hollows is a function of the shading which is ambiguous, depending on the direction of the light. One interpretation of this is that we assume that the light comes from above rather than that the objects face one direction and the different shadings result from different light sources. In the Maurits Escher repeated pattern of fishes and birds (Plate 1.1), the same outline is shared by the two different figures. As contours normally only outline an object against its background, Helmholtz’s theory holds that the visual system selects either the fishes or the birds for attention, with the other becoming background.

Fig. 1.3. a: the Kanizsa illusion. b: the Ponzo illusion. (Glynn, 1999, p. 196.)

Fig. 1.4. The Adelbert Ames distorting room. (Glynn, 1999, p. 196.)

Fig. 1.5. Ramachandran’s bumps and hollows. (Glynn, 1999, p. 196.)

Contemporary neuroscientists support Helmholtz’s theory. Thus Glynn comments that ‘explanations of this kind do not tell us how the brain manages to make the inferences though they provide a clue to the kind of information processing that may be involved’ (Glynn, 1999, p. 195), and Kandel and his colleagues suggest that ‘Illusions illustrate that perception is a creative construction based on unconscious conjecture about many of the assumptions the brain makes in interpreting visual data’ (Kandel et al., 1991, p. 433). Furthermore, Damasio emphasizes that

When you and I look at an object outside ourselves, we form comparable images in our respective brains. … But that does not mean that the image we see is the copy of whatever the object outside is like. Whatever it is like, in absolute terms, we do not know. The image we see is based on changes which occurred in our organisms … when the physical structure of the object interacts with the body. … The object is real, the interactions are real, and the images are as real as anything can be. And yet, the structure and properties in the image we end up seeing are brain constructions prompted by the object. … There is … a set of correspondences between physical characteristics of the object and modes of reaction of the organism according to which an internally generated image is constructed. (Damasio, 1999, p. 320)

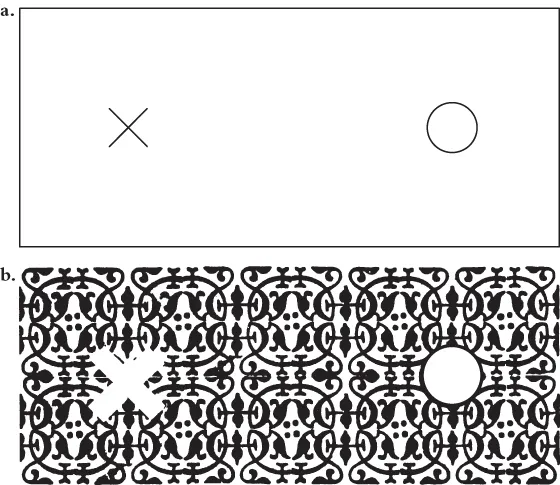

A phenomenon that is often used to provide what is taken to be a rather dramatic example of the extent to which the cortex makes inferences based on visual sensations to arrive at what we perceive is given by the phenomenon of ‘filling in’. Fig. 1.6a presents a black cross and a circle on a white background, which should be viewed about 25 cm away with the left eye closed. Focus on the cross and slowly bring the figure towards your right eye; the circle will eventually disappear from your vision, as the image falls on the part of the retina where the optic nerve begins and there are no photoreceptors present. This is your ‘blind spot’. Contemporary neuroscientists, following Helmholtz, suggest that the visual cortex fills in the gap in the blind spot to make it the same as the white background or surroundings. A more dramatic example of this ‘filling in’ is given by repeating this kind of experiment but using instead fig. 1.6b, which instead has a white cross and a white disc on a patterned background. This time focus on the white cross and slowly bring the figure towards the right eye with the left eye closed as before. Again the disc disappears, but this time the pattern is continuous across the region previously occupied by the disc. Thus, it would seem, the blind spot does not normally give rise to a black area in one’s visual field but is continually ‘filled in’ by an unconscious inference during normal vision.

Fig. 1.6. The phenomenon of ‘filling in’. (Glynn, 1999, p. 199.)

1.1.1 Misdescription of visual illusions by cognitive scientists

Helmholtz and his contemporary followers interpret visual illusions in terms of the particular theory of perception, mentioned above: namely, that physical stimuli to the retina are transmitted to the brain, where they become sensations, which are conceived to be the raw material from which perceptions are synthesized by the unconscious mind. However, this theory is incorrect. For there are no visual ‘sensations’ in the brain, although pressure on the brain may produce a sensation: namely, a headache. There is no such thing as combin-ing sensations to form a perception. Furthermore, perceptions cannot be conclusions of unconscious inferences the premisses of which are unconscious and more or less indescribable sensations and (unconscious) generalizations about the correlations between past sensations and objects perceived. So illusions, such as the Ponzo illusion, Kanizsa’s illusion, and the Ames room illusions, are not explicable in Helmholtz’s terms.

To perceive something is not to form a hypothesis. A hypothesis is an unconfirmed proposition or principle put forward as a provisional basis for reasoning or argument, a supposition or conjecture advanced to account for relevant facts. Only human beings, not their brains, can form hypotheses and make inferences. There is no such thing as a brain’s putting forward a proposition as a basis for reasoning or argument or acting on a supposition. Hypotheses are formed on the basis of data which consist of information that is thought to provide evidential support for the hypothesis. However, the brain does not, and could not have, information in this sense. Only thinking creatures with brains can form hypotheses or conjectures on the basis of the information available to them.

A perception – i.e. a person’s perceiving something – is not a hypothesis, but an event or occurrence, and so cannot be the conclusion of an inference, which is a proposition, not an event or occurrence. Finally, inferences are neither conscious nor unconscious mental processes. For inferences are not processes at all. Rather, inferences are transformations of propositions in accordance with a rule, derivations of propositions from premisses in conformity with a pattern of derivation. But perceiving something does not involve transformations of propositions by a perceiver (or his brain).

Locke, and the British empiricist tradition that he originated, conceived of ideas and impressions as the result of the impact of the material world on our nerve endings. This misconception is the source of the thought that perceiving always involves sensations which are, on Helmholtzian theory, the premisses of unconscious inferences. For Helmholtzian ‘sensations’ are, in effect, empiricist ‘ideas’ or ‘impressions’. It is also the source of the equally misguided and far more widespread thought that what is seen (or heard, etc.) when we see (or hear, etc.) something is a picture or image (visual or auditory). This representationalist view is defended by Damasio above, but is confused. For what one perceives by the use of one’s perceptual organs is an object or array of objects, sounds and smells, and the properties and relations of items in one’s environment. It is a mistake to suppose that what we perceive is always, or even commonly, an image, or that to perceive an object is to have an image of the object perceived. One does not perceive images or representations of objects unless one perceives paintings or photographs of objects. (Of course, one may have after-images or conjure up mental images, but one does not perceive them.)

1.2 Gestalt Laws of Vision

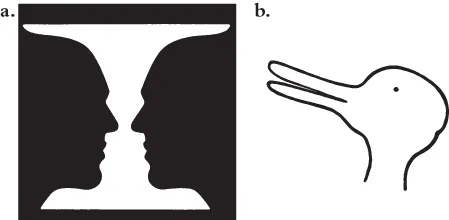

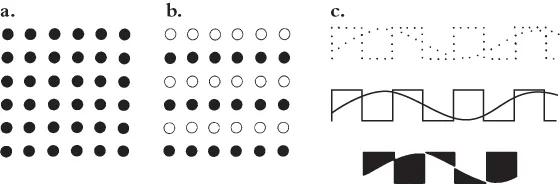

After the First World War, Max Wertheimer (1924), Kurt Koffka (1935) and Wolfgang Köhler (1929), following Helmholtz, determined to find the laws that relate what we perceive to what we are actually looking at. In particular, they were concerned with how the overall configuration of a scene, rather than particular elements in it, informed the interpretation of the scene. The way in which the Gestalt or configuration of the scene provides us with an interpretation is dramatically illustrated by means of Edgar Rubin’s vase or two faces (fig. 1.7a), depending on what is assumed to be background or figure, or by Jastrow’s duck–rabbit (fig. 1.7b). The laws formulated by the Gestalt psychologists are illustrated by means of fig. 1.8. The ‘law of proximity’ is shown by the fact that the circles in fig. 1.8a are seen as arranged in horizontal or vertical lines rather than oblique lines, because they are further apart in the oblique lines. The ‘law of similarity’ is illustrated by fig. 1.8b, in which the dots are now seen as horizontal lines because those forming horizontal lines are more similar than those forming vertical lines. An example of the ‘law of good continuation’, which states that we perceive the organization that interrupts the fewest lines, is shown in fig. 1.8c, in which the small dots are seen to form a wavy line superimposed on a profile of battlements rather than as the succession of shapes shown at the bottom of the figure. Cognitive scientists believe that Gestalt psychology has shifted the fundamental empiricist’s question ‘What are the basic components of this perception?’ to ‘What neural transformation produces this perception?’, thus offering a common scheme for merging psychological and neurobiological investigations into the process of vision.

Fig. 1.7. a: Edgar Rubin’s vase or two faces. b: Jastrow’s duck–rabbit. (Glynn, 1999, p. 199.)

Fig. 1.8. Illustrations of the Gestalt ‘Laws’ of (a) ‘proximity’; (b) ‘similarity’; (c) ‘good continuation’. (Glynn, 1999, p. 200.)

1.3 Split-Brain Commissurotomy; the Two Hemispheres may Operate Independently

Patients with intractable epilepsy often undergo surgery to relieve the condition. This involves cutting the corpus callosum that connects the two halves of the brain. In the early 1960s Michael Gazzaniga and Roger Sperry showed that the two hemispheres of such patients possess their own specializations, with the left hemisphere dominant for language and speech and the right being largely causally responsible for visual motor tasks (Gazzaniga and Sperry, 1967). If a visible object (or picture of an object) occurs in the right visual field (so that concomitant neuronal activity occurs only in the left hemisphere) of such split-brain patients, then they can describe what they see; but if the visible object occurs in the left visual field (with concomitant neuronal activity restricted to the right hemisphere), they cannot. In this case, the patients could point at a similar object to that presented in their left visual field if asked to, but they were not able to say what it was (Gazzaniga et al., 1965).

Similar results were found for the other sensory modalities of touch, sound and smell. In addition, the right hemisphere was shown to be causally responsible for the processes involved in controlling the left hand, whereas the left hemisphere was causally implicated in the control of the right hand. Gazzaniga and Sperry concluded that each hemisphere in humans is causally implicated in different aspects of thought and action. Fig. 1.9a shows the kind of experimental set-up used by Gazzaniga and Sperry to collect data in early split-brain studies (see Gazzaniga, 1995; Baynes and Gazzaniga, 2000). Presenting a written name for an object to the left visual field (involving the right hemisphere) of a patient provides the condition for the patient to use his left hand to select the correct object by touch (in this case ‘spoon’; Gazzaniga, 1983). In fig. 1.9b, when presented with bilateral picture displays, the patient confabulates about the choices he previously made with his left hand. As Gazzaniga describes the experiments, the right hand sel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Perceptions, Sensations and Cortical Function: Helmholtz to Singer

- 2 Attention, Awareness and Cortical Function: Helmholtz to Raichle

- 3 Memory and Cortical Function: Milner to Kandel

- 4 Language and Cortical Function: Wernicke to Levelt

- 5 Emotion and Cortical-Subcortical Function: Darwin to Damasio

- 6 Motor Action and Cortical-Spinal Cord Function: Galen to Broca and Sherrington

- 7 Conceptual Presuppositions of Cognitive Neuroscience

- References

- Index

- Color Plates