- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The computing profession faces a serious gender crisis. Today, fewer women enter computing than anytime in the past 25 years. This book provides an unprecedented look at the history of women and men in computing, detailing how the computing profession emerged and matured, and how the field became male coded. Women's experiences working in offices, education, libraries, programming, and government are examined for clues on how and where women succeeded—and where they struggled. It also provides a unique international dimension with studies examining the U.S., Great Britain, Germany, Norway, and Greece. Scholars in history, gender/women's studies, and science and technology studies, as well as department chairs and hiring directors will find this volume illuminating.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I: Tools for Understanding

1

Gender Codes

Defining the Problem

Women have passionately programmed computers for many decades. Ada Lovelace wrote abstract programs for calculating Bernoulli numbers on Charles Babbage’s mechanical computer, and six women mathematicians, known as human “computers,” created working programs for the ENIAC computer during the Second World War. In the 1950s the pioneering generation of computer science featured a surprising number of prominent women who led research teams, defined computer languages, and even pioneered the history of computing. The annual Grace Hopper celebration, named for the most prominent of these pioneering women computer scientists, offers “a four-day technical conference designed to bring the research and career interests of women in computing to the forefront”[1]. More recently, Elizabeth “Jake” Feinler defined the top-level domain names—.com, .gov, .org—for the Internet. In 2006, Fran Allen, already the first female IBM Fellow, was the first woman to win the prestigious Turing Award from the Association for Computing Machinery, for her work in optimizing computer code. Two years later, Barbara Liskov was awarded the Turing Award for her foundational work on programming languages. The list of notable women in computing is sizable and expanding. It’s strange anyone would think that women don’t like computing.

Since the 1970s women have made impressive gains in professional life, but these gains did not extend evenly into the fields of engineering and the physical sciences. Greater gender parity has typified most professions in the past two decades or so, with women making up half or more of all graduate or professional students: this is true for law schools and medical schools as well as most fields in the social and biological sciences. Engineering and physical sciences started with rather few women, at all levels, and have been making slow if steady progress in enrolling more women students and hiring more women faculty and scientists. Retaining women scientists and engineers at mid-career remains a challenge. But when you look at the college enrollments and workforce figures for computing, a strikingly different picture emerges.

There’s no way of putting it except to say that computing is unique among all the professional fields. You can see this most clearly when looking at the “big picture” across the last 40 years and identifying which of the technical professions women opted to enter and when they did so. The first distinction for computing was an early upside in women’s participation. Beginning in the mid-1960s, women entered the emerging computing profession and eventually did so in unusually large numbers (Fig. 1.1). In the United States, women went from being roughly one in ten in the undergraduate computing cohort to being nearly four in ten. At the peak in the mid-1980s women earned 37% of all U.S. bachelor degrees in computing, and across these decades women entered the computing workforce in large numbers. In the late 1980s, women constituted fully 38% of the U.S. white-collar computing workforce. This was a significant success for computing and for the women’s movement. Chapters in this volume describe why, for roughly two decades, computing attracted so many women.

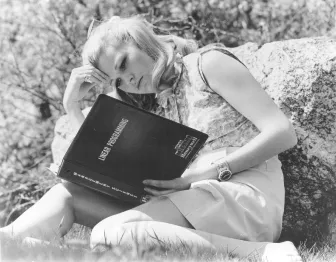

Figure 1.1. Woman studying linear programming. For recruiting, Honeywell created a positive image of women programmers in 1969. Women, such as Christine Johnson, composed one-third of the opening class of 40 at Honeywell’s Wellesley Hills, Massachusetts, education center. (Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute.)

We need to better understand why women elected to study computing in such large numbers. Why not chemistry or physics or engineering or one of the other technical professions? Men through the 1960s soundly dominated all of these fields. In this book we explore why large numbers of women experienced programming and other computer-related jobs to be more congenial than working in science labs or in engineering offices. We show that women worked as programmers, as systems analysts, as managers, and as computer executives. In the mid-1980s, while women flooded into computing education and from there into the computing workforce, there were proportionately more women in computing than anywhere else in the engineering world. Medical school was to a large degree still a boy’s club, with sizable increases in women medical students just beginning. (Only psychology and certain of the social sciences had equal numbers of women and men; and, of course, the professions of nursing, teaching, librarianship, and social work were, from their origins earlier in the 20th century, distinctively hospitable to women.) This book tells the stories of women computing professionals, including accounts of their struggles and celebrations of their successes. The chapters also give visibility to the many women who worked in lower-status and lower-pay computer occupations, such as operators and data-entry clerks (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Women as computer operators. Publicity images often used attractive women models to sell computer systems. But many women actually worked as computer operators, here on an OCR data-entry system, a decided step up from data-entry work (compare Fig. 1.6). (Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute.)

Despite these early successes, something unprecedented in the history of the professions hit computing in the mid-1980s: not merely did women stop entering computing in large numbers, but the proportion of women studying computing actually began falling—and it has continued to fall, steadily, all the way through to the present. No other professional field has ever experienced such a decline in the proportion of women in its ranks. The latest figures from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Computing Research Association, the Department of Education, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics using various measures and methodologies all tell the same story: women are staying away from computing education and the computing workforce. The most recent NSF figures suggest that women may account for just one in seven undergraduate computing students, or around 15%: a catastrophic drop from the peak of 37%. The Taulbee survey of top-ranked North American computer science and engineering programs puts the recent figures even lower [2]. A minuscule 0.4% of first-year women college students list computer science as a probable major, while as recently as the early 1980s it was fully ten times higher. Even when combining computer science with information science, which has more women students, the trend is unmistakable—and it is down [3].

We initially thought this drop was “only” a problem for academic computer science, but closer inspection of the data indicates there has been a gender-specific tail-off in the computing workforce as well. Recent figures from 2005 indicate that women composed just 29% of the white-collar computing workforce, down nearly 10 percentage points from the 1980s. Clearly, this is not merely an academic problem. Of course, not all practicing programmers have computer science degrees, and indeed only around two-thirds of working programmers and systems analysts have 4-year college degrees of any sort. A large number of computer professionals enter the workforce with associate degrees or other vocational training. (Gender statistics for these vocational programs are not carefully scrutinized by national policymaking bodies; the same goes for proprietary courses offered by Microsoft, Oracle, and other companies.)

A recent report from the Harvard Business School anatomizes the sharp falloff of women in science, engineering, and other technical companies. Most women continue work in these technical fields, including computing, for approximately 10 years—and then fully half of them leave the workforce. This mid-career exodus is not the result of women’s “choices” or “preferences” (as some commentators suggest) because, after all, these women actually chose those professions. Rather, “more than half of these women [working in science and technology fields] drop out—pushed and shoved by macho work environments, serious isolation, and extreme job pressures” [4]. This loss of women’s talent is alarming. Figures that we obtained from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that women’s presence in the computing workforce is falling off as well. Worse, the falloff in workforce closely follows the downturn in undergraduate computer science graduates—with perhaps as little as a 3-year “lag.” If women were leaving the computing workforce after 10 years, that would be bad enough. It appears that the fall in enrollments, number of graduates, and computing workforce numbers are closely related. Indeed, we suspect that the educational and workforce tail-offs together actually reflect some broader, as-yet-unrecognized social or cultural shift. If the employment figures continue to fall as abruptly as the enrollment figures might forecast, then the computing workforce will soon become one of the most gender-segregated professional environments. Computing might return to its gender composition of the 1960s, but the rest of the world has moved forward.

A pressing question that this book addresses, and for the first time with historical data and analysis, is how and when and why women’s participation in computing fell so dramatically. This lopsided change in computing’s gender balance in the past two decades is entirely without historical precedent. Some of the technical professions appear historically to be resistant to women’s entry, such as surgery or civil engineering; yet no other profession has seen the upswing and downturn of women that is strikingly evident in computing. There have been wide swings in the enrollments and employment of varied branches of engineering, as one field or another comes into fashion or falls from favor; these swings are not accompanied by any similar long-term decline in women.

FRAMING THE GENDER GAP

The dramatic falloff of women in computing is hardly a secret. In 1991 Ellen Spertus, then an MIT graduate student, wrote a paper asking, “Why Are There So Few Female Computer Scientists?” The problem was not so much formal discrimination or overt barriers to women, but rather gender biases encoded in professional culture. Among her findings, Spertus reported a professor introducing robotics to a graduate artificial-intelligence class by telling this would-be joke: “Pretty soon we’ll have robots that are sophisticated enough to wander around in shopping malls and pick up girls.” Unsurprisingly, the female graduate student who related the episode hardly heard the rest of the lecture. In the years since Spertus’s report, the situation has not gotten better. “What Has Driven Women Out of Computer Science?” was one recent headline. “Lack of Women in Computing Has Educators Worried,” goes another. The IEEE Spectrum [5] warns that the “gender gap is widening.”

The gender gap in computing now concerns professionals in the field as well as educators concerned about the composition of their classrooms. Women’s absence has contributed to a sharp contraction in U.S. computing enrollments: in 2001 there were 400 majors in each computer science (CS) department, while today there are just over 200. In recent years, the National Science Foundation has put around $20 million annually into various research and demonstration efforts aimed at increasing the participation of women in computing and other science and engineering fields [6]. Educators from K-12 through graduate school encourage young women to study math and science as well as to major in engineering fields, including computer science and electrical engineering. Professional associations mobilize high-level committees of educators and practitioners. Some researchers examine gender as an important variable in designing software and human–computer interfaces, addressing a gender bias broadly similar to medical researchers’ past assumption that men’s bodies were the normal ones [7]. And science museums, science-fair mentors, Girl Scout leaders, and many others present positive views of science and technical fields as approachable, exciting, and relevant to young women as they plan careers. It’s difficult to assess their impact, but it’s a safe bet that absent these wide-ranging efforts the worrisome figures on women in computing might be even worse.

We believe that there is some “missing piece” to this picture. Our book is aimed—in three distinct ways—at assisting these reform efforts and, we hope, changing the culture of computing. First, we offer forceful historical data documenting the gender gap in computing. It’s very clear that smart people have devised many intervention strategies, based on intuitively plausible models of the underlying problem [8]. Yet, surprisingly, not enough is known about how and when and why the gendered culture of computing emerged. This book addresses these very questions. We hope historical insight can improve the outcomes for the wide-ranging efforts at change. Richly textured case studies of women’s struggles as well as their own strategies for success, in gaining computing education as well as working for and even running computing companies, can help evaluate and refine these intervention strategies. While we know that women flooded into the computing professions in the 1960s and 1970s, we know all too little about why they did so and what they found there. Women’s experiences in the computing workforce are similarly underdocumented and poorly understood [9]. In this book we present fresh evidence of women’s striking successes as computer scientists and as entrepreneurs in the computer services industry. This book also documents women’s exclusion from high-level computing positions and marginalization within the computing professions. These stories, too, give a more complete picture of the problem.

A second contribution of this book is to offer tools for grasping the dynamics of the gender gap. The computing profession changed dramatically across the past three or four decades. We need to record the stories but we also need tools for understanding what was going on, what might have gone wrong, and, for those early decades, what clearly went right with women in computing. Historians, by our disciplinary training, are ideally equipped to understand complexity and change across time. Historians study social processes as well as cultural dynamics; as a profession we deal centrally with language, representations, cultural forms, institutional practices, social and political processes—and power. “The study of computer science education can be seen as a microcosm of how a realm of power can be claimed by one group of people, relegating others to outsiders,” as Margolis and Fisher argue in Unlocking the Clubhouse. There are “weighty influences that steal women’s interest in computer science away from them” [10]. Historians’ contributions frequently involve not merely accurately reporting the facts, but also unpacking complex terms at play. Here, it is certain that we need to unpack the terms “women” and “men” and “computing” and to set these into a dynamic framework. Women faced different expectations about gender roles and career paths in the 1960s compared with the 1980s, while computing during these decades was transformed from large mainframe-based installations to the profusion of personal computers. It is worth noting that women flooded into computing during the mainframe era as well as that the sea change in gender occurred during the rise of personal computers in the 1980s.

This book profiles the astonishing diversity of women’s experiences in the “computing profession” as well: they worked as highly paid programmers and systems analysts and managers, as well as lower-status operators, data-entry clerks, and maintenance workers. Some of these women, especially ones with managerial or executive responsibilities, are at the upper scale of white-collar work, while the lower-status jobs are squarely blue-collar ones. A key process that we document and analyze is the “feminization” of work as well as the “masculinization” of the professions. This book highlights how computing is understood in gendered terms and how i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title page

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- Part I: Tools for Understanding

- Part II: Institutional Life

- Part III: Media and Culture

- Part IV: Women in Computing

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Gender Codes by Thomas J. Misa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Computer Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.