![]()

PART I

Overview of Financial Derivatives

Part One consists of four introductory chapters intended to open the world of financial derivatives to the reader. In Chapter 1, “Derivative Instruments: Forwards, Futures, Options, Swaps, and Structured Products,” Gary D. Koppenhaver takes a generalist approach to forwards, futures, swaps, and options. He approaches these instruments from the point of view of their suitability to address a single problem: managing financial risk. Through this approach, he shows that these instruments obey common principles and are closely related from a conceptual point of view. Koppenhaver strives to emphasize the connections among these different types of derivatives in order to demystify derivatives in general.

One of the largest differences among derivatives turns on the manner in which they are traded—on exchanges or in the more informal and less structured over-the-counter market? Sharon Brown-Hruska contrasts these two models for trading derivatives in Chapter 2, “The Derivatives Marketplace: Exchanges and the Over-the-Counter Market.” In light of the financial crisis, many legislators are pressing to reduce or eliminate the over-the-counter market, which is actually much larger than the market for exchange-traded derivatives. However, many believe that trading derivatives on exchanges make them more transparent, easier to regulate, and less likely to lead to derivatives disasters.

From the point of view of derivatives, we might think of speculation as trading derivatives in a manner that increases the investor’s risk in order to pursue profit. Hedging by contrast is trading derivatives in order to reduce a preexisting risk. In Chapter 3, “Speculation and Hedging,” Gregory Kuserk shows how hedging and speculation differ but also explains how one might think of hedging and speculating as two sides of the same coin, with the relationship between the two activities being much closer than is generally recognized.

The editors of this volume believe that Chapter 4 by Christopher L. Culp, “The Social Function of Financial Derivatives,” is one of the most important in the entire volume. As discussed in the introduction to this book, there is a recurring impulse to eliminate derivatives markets through legislative action. Culp shows how derivatives markets serve society in a variety of ways, some of which are quite obvious and others of which are more sophisticated.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Derivative Instruments

Forwards, Futures, Options, Swaps, and Structured Products

G. D. KOPPENHAVER

Professor and Chair, Department of Finance, Insurance and Law, Illinois State University

INTRODUCTION

The evolution of ideas in finance usually is driven by circumstances in financial markets. In the early 1980s, at the inception of cash-settled financial futures contracts, the term derivatives was most often associated with financial rocket science. Esoteric derivative contracts, especially on financial instruments, faced a public relations probem on Main Street. By the mid-1990s, the term derivatives carried a negative connotation that conservative firms avoided. High-profile derivative market losses by nonfinancial firms, such as Metallgesellschaft AG, Procter & Gamble Co., and Orange County, California, caused boards of directors to look askance at derivatives positions.1 In the early 2000s, however, derivatives and their use are a real part of a discussion of business tactics. While it is still the case that derivatives contracts are a powerful tool that could damage profitability if used incorrectly, the discussion today does not focus on why derivative contracts are used but how and which derivative contracts to use.

The goal of this chapter is to take a generalist approach to closely related instruments designed to deal with a single problem: managing financial risk.2 In the chapter, forwards, futures, swaps, and options are not treated as unique instruments that require specialized expertise. Rather the connection between each class of derivative contracts is emphasized to demystify derivatives in general. As off-balance sheet items, each is an unfunded contingent obligation of contract counterparties. Later in the chapter, the discussion returns full circle to consider the creation of funded obligations with derivative contracts, called structured products. Structured products are financial instruments that combine cash assets and/or derivative contracts to offer a risk/reward profile that is not otherwise available or is already offered but at a relatively high cost. The repackaging of off-balance sheet credit derivatives into an on-balance sheet claim is shown through a structured investment vehicle example.

Uncertainty is a hallmark of today’s global financial marketplace. Unexpected movements in exchange rates, commodity prices, and interest rates affect earnings and the ability to repay claims on assets. Great cost efficiency, state-of-the-art production techniques, and superior management are not enough to ensure firm profitability over the long run in an uncertain environment. Risk management is based on the idea that financial price and quantity risks are an ever-increasing challenge to decision making. In responding to uncertainty, decision makers can act to avoid, mitigate, transfer, or retain a commercial risk. Because entities are in business to bear some commercial risk to reap the expected rewards, the mitigation or transfer of unwanted risk and the retention of acceptable risk is usually the outcome of decision making. Examples of risk mitigation activities include forecasting uncertain events and making decisions that affect on-balance sheet transactions to manage risk. The transfer of unwanted risk with derivative contracts, however, is a nonintrusive, inexpensive alternative, which helps explain the popularity of derivatives contracting.

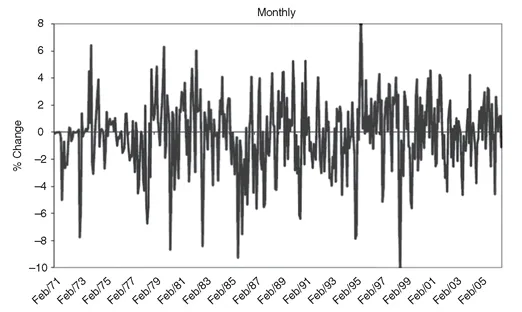

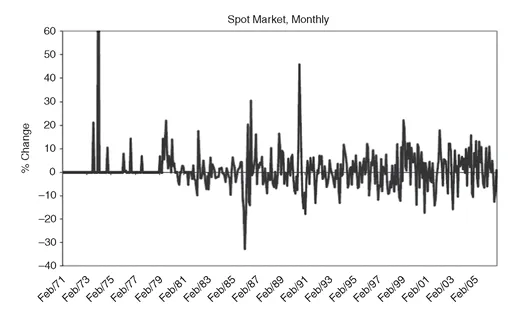

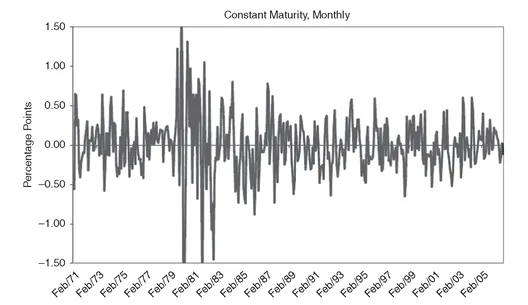

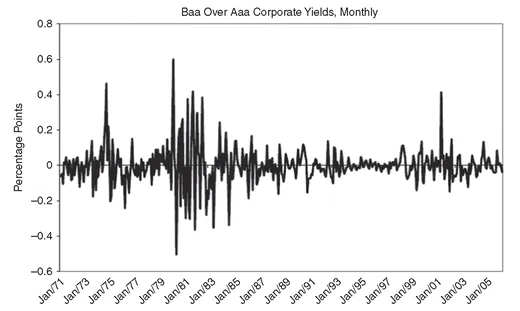

Consider Exhibits 1.1 through 1.4 as part of the historical record of volatility in financial markets. Exhibit 1.1 illustrates the monthly percentage change in the Japanese yen/U.S. dollar exchange rate following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods Agreement in the early 1970s. The subsequent exchange rate volatility helped create a successful Japanese yen futures contract in Chicago. In Exhibit 1.2, the monthly percentage change in a measure of the spot market in petroleum is illustrated. While significant spikes in price occur around embargos or conflict in the Middle East, price volatility has not lessened over time for this important input to world economies. U.S. interest rates are also a source of uncertainty. The change in Federal Reserve operating procedures in the late 1970s temporarily increased volatility, but significant uncertainty in Treasury yields has remained over time. Exhibit 1.4 illustrates the past history of default risk premiums. Most recently, a sharp spike in default risk premiums occurred at the end of the stock market technology bubble in the early 2000s. Across all graphs, it should be clear that uncertainty in economically important markets is not decreasing over time and that the effectiveness of forecasting changes in prices, rates, or spreads as a method to mitigate the uncertainty is not likely to be high.

Exhibit 1.1 Percent Change in Yen/U.S. $ Exchange Rate

Exhibit 1.2 Percent Change in West Texas Oil Prices

Exhibit 1.3 Change in 5-Year Treasury Yield

Exhibit 1.4 Credit Risk Premium Change

A GENERALIST’S APPROACH TO DERIVATIVE CONTRACTS

What are derivative contracts? A derivative contract is a delayed delivery agreement whose value depends on or is derived from the value of another, underlying transaction. The underlying transaction may be from a market for immediate delivery (spot or cash market) or from another derivative market. A key point of the definition is that delivery of the underlying is delayed until sometime in the future. Economic conditions will not remain static over time; changing economic conditions can make the delayed delivery contract more or less valuable to the initial contract counterparties. Because the contract obligations do not become real until a future date, derivative contract positions are unfunded today, are carried off the balance sheet, and the financial requirements for initiating a derivative contract are just sufficient for a future performance guarantee of counterparty obligations.

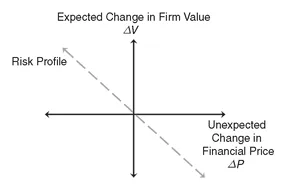

Before beginning a discussion of contract types, it is helpful to depict the profiles of the commercial risks being managed with derivative contracts. The first step in any risk management plan is to accurately assess the exposure facing the decision maker. Consider Exhibit 1.5, which plots the expected change in the value of a firm, ΔV, as a function of the unexpected change in a financial price, ΔP. The price could be for a firm output or for a firm input. The dashed line indicates that as the price increases (ΔP > 0) unexpectedly, the value of the firm falls. The specific relationship is consistent with many conditions, such as an unexpected rise in input cost, a loss of significant market share as output prices unexpectedly rise, or even a rise in the price of a fixed income asset due to an unexpected decline in yields. The key is simply that the unexpected price rise causes the expected value of the enterprise to fall.

Exhibit 1.5 A Commercial Risk Profile

It is also instructive to ask whether there are alternatives to derivative contracts in managing commercial risks. Significant, low-frequency commercial risks are transferred through insurance contracts, for example. While virtually any risk can be insured, negotiation costs and hefty premiums may prevent insurance from being a cost effective mechanism for risk transfer. On-balance sheet transactions such as the restructuring of asset and/or liability accounts to correct an unwanted exposure are another alternative to derivative contracts. Customer resistance to restructuring may affect profitability as, say, a squeeze on net interest income results when a bank offers discounts on loans or premium deposit rates to accomplish the restructuring. Finally, firms can exercise their ability to set rates and prices to transfer risk to customers and stakeholders. Such exercise of market power as an alternative to derivative contracting depends on the degree of competition in output and input markets. Firms facing different competitive pressures may have different preferences for derivatives relative to other risk transfer methods.

Forward Contracts

The most straightforward type of derivative contract is a contract that transfers ownership obligations on the spot but delivery obligations at some future date, called a forward contract. One party agrees to purchase the underlying instrument in the future from a second party at a price negotiated and set today. Forward contracts are settled once—at contract maturity—at the forward price agreed on initially. Industry practice is that no money changes hands between the buyer and seller when the contract is first negotiated. That is, the initial value of a forward contract is zero. As the price of the deliverable instrument changes in the underlying spot market, the value of a forward contract initiated in the past can change.

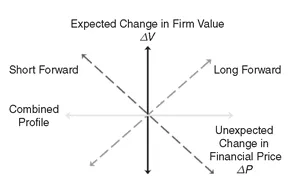

To illustrate the value change in a forward contract, consider Exhibit 1.6. All other things equal and for every unexpected dollar increase in the financial price, ΔP, an agreement to purchase (long forward) the underlying instrument at the lower forward price increases expected firm value, ΔV. Alternatively, Exhibit 1.6 shows that an agreement to sell (short forward) the underlying instrument at the lower forward price decreases expected firm value. The forward contract long (short) benefits from the contract if the underlying instrument price rises (falls) before the contract matures. The exhibit also shows that both buying and selling exactly the same forward contract create a combined position that makes the firm value insensitive to unexpected changes in the underlying price (the horizontal axis). Comparing Exhibits 1.5 and 1.6, the commercial risk profile in Exhibit 1.5 is the same as the risk profile for a short forward contract. To hedge away the risk or make the firm insensitive to unexpected changes in the underlying price, the firm should enter into a long forward contract (Exhibit 1.6).

Exhibit 1.6 Risk Profiles for Forward Contracts

A feature of a forward contract is that the credit or default risk implicit in delayed delivery performance is two-sided. The default risk is real because most forward contracts are settled by physical delivery. Recall the forward contract buyer can either make a gain or take a loss depending on the forward price set initially and the price of the underlying at contract maturity. If the underlying instrument price rises (falls), the contract buyer gains (loses) on the forward contract. Because the value of the contract is settled only at contract maturity and no payments are made at origination or during the term of the contract, a forward contract buyer is exposed to the credit risk that the seller will default on forward contract delivery obligations when the underlying asset can be sold for more in the spot market. Likewise, a forward contract seller is exposed to the credit risk that the buyer will default on forward contract payment obligations when the underlying asset can be purchased for less in the spot market.

Consider a forward rate agreement as an example of a forward contract on interest rates. A forward rate agreement is an agreement to pay a fixed interest rate on a pre-determined, notional principal amount and receive a floating rate cash flow on the same notional principal amount at contract maturity. Note that only the interest cash flows are intended to change hands at contract maturity. If the floating rate return is higher than the fixed rate cost agreed to at contact initiation, the forward rate long gains the difference in cash. If the floating rate return is lower than the fixed rate cost agreed to at contact initiation, the forward rate short gains the difference in cash. The forward rate long gains if interest rates rise or fixed income prices fall over the life of the contract. A map of the forward rate agreement cash flows is illustrated in

Exhibit 1.7, where

is the fixed rate set at contract origination, time 0, and

is the actual rate realized at tim...