![]()

Chapter 1

Spectroscopic Theory for Chemical Imaging

M. J. Pelletier

Pfizer, Groton, CT, USA

C. C. Pelletier1

NASA—Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Gales Ferry, CT, USA

1Retired

1.1 Introduction

All images require some type of contrast to differentiate regions of interest in a field of view. The most common source of image contrast is variation in the intensity of reflected light. Contrast can, however, be based upon any measurable property of the sample that can be expressed as a function of location. Contrast is improved for measurements having a wider dynamic range and by measuring a larger number of variables for each pixel, as in color versus black-and-white photography. Contrast may also be enhanced with one or more of a wide range of techniques including digital image processing and structured illumination. This book will focus on chemical images generated using vibrational spectroscopic contrast. Such contrast is generated by quantifying one or more attribute(s) of an infrared absorption, infrared emission, or Raman scattering spectrum for each pixel. By providing a window into the spatial distribution of properties such as molecular composition, structure, state, and concentration, images based on vibrational spectroscopies open up a new way of seeing the world.

Imaging can be accomplished by measuring a property from the entire field of view simultaneously (global imaging) or by measuring a property from individual points in the field of view sequentially and combining the points to create the image (mapping). Since mapping requires a large number of measurements, each measurement must be relatively fast for mapping to be practical. For example, an image consisting of 640 × 480 pixels contains over 300,000 measurements and would take more than 3.5 days to acquire if each measurement required 1 s. Mapping speed can be increased by simultaneously measuring a property at multiple points in a subregion of the field of view and combining those subregions to create the image. The subregion may consist of a single column of measurement points (line imaging) or may contain multiple columns (mosaic imaging). In most cases, even global imaging requires multiple frames, each containing different spectroscopic information, to be collected sequentially and overlaid to form a single image. Sample changes during the course of sequential measurements can confound the interpretation of spectral images.

This chapter provides an introduction and theoretical background for vibrational spectroscopies, as used to produce chemical images. Infrared, Raman, and related spectra result from the interactions of electromagnetic radiation with molecular vibrations, so this chapter begins with a description of relevant aspects of molecular vibration, followed by a section on electromagnetic radiation and its interactions with matter. Next are three sections on infrared spectroscopies, divided by spectral region. After that, several different types of Raman spectroscopy that are used for chemical imaging are described. The final section briefly presents the use of Raman and infrared spectroscopies for creating large chemical images by remote sensing. Remote sensing is probably responsible for the majority of chemical images created because of its use in mapping the atmosphere, planets including Earth, and moons, and in astronomy.

1.2 Molecular Vibrations

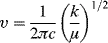

A chemical bond between two atoms can be modeled as a spring connecting two point masses. If the spring follows Hook's law, the force it applies between the two point masses will be proportional to the spring displacement from its lowest energy position. The system, called a harmonic oscillator, will have a single resonant vibrational frequency, υ, given by

where c is the speed of light, k is the force constant, and μ is the reduced mass, mamb/(ma + mb).

Equation 1.1 describes the vibrational frequency of diatomic molecules reasonably well. Increasing the strength of the chemical bond increases the vibrational frequency. Increasing the atomic mass reduces the vibrational frequency.

The force applied by a chemical bond does not follow Hook's law exactly, though. Atoms have finite size and cannot occupy the same space. As a result, the repulsive force increases much more quickly than Hook's law would predict as the atoms get close together. As the atoms get further apart the chemical bond weakens, approaching zero strength at infinite separation, again violating Hook's law. Deviations from Hook's law are amplified by disparity between the molecular masses. Vibrating systems that do not follow Hook's law are called anharmonic, and the extent to which they deviate from an ideal harmonic oscillator is called anharmonicity. Anharmonicity has a relatively small role in most forms of Raman spectroscopy, a somewhat larger role in mid-infrared (mid-IR) spectroscopy, and is of primary importance in near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy.

Vibrations in molecules containing more than two atoms are more complicated. The total number of different, or normal, vibrations (ignoring anharmonicity) in a molecule with n atoms is 3n − 5 for a linear molecule and 3n − 6 for a nonlinear molecule. For example, an anthracene molecule has 24 atoms and therefore 66 normal vibrations. Some of these vibrations have exactly the same frequency (called degenerate vibrations). Other vibrations produce no signal for a particular type of vibrational spectroscopy due to symmetry constraints. As a result of these spectral simplifications, even most large molecules have manageable vibrational spectra.

Oscillators sharing a common atom may exert forces on each other when they oscillate. If the oscillator frequencies are very different from each other, each oscillator remains fairly independent of the other. If the frequencies are similar, though, the oscillators can couple, essentially forming a new single oscillator with new frequencies. Consider the linear CO2 molecule. Both carbon–oxygen bonds are identical. They couple to form a single oscillator having two different vibrations. One vibration consists of each carbon–oxygen bond stretching in phase, resulting in a vibration where the carbon atom does not move. This in-phase vibration is an example of a symmetric vibration. The other vibration consists of the carbon–oxygen bonds stretching out of phase with each other, resulting in a vibration where the carbon atom moves and the oxygen atoms do not. This out-of-phase vibration is an example of an antisymmetric vibration. In general, the antisymmetric vibration tends to be at higher frequency and the symmetric vibration tends to be at lower frequency than the natural frequency of the uncoupled oscillators.

Groups of atoms in a molecule that are not vibrationally coupled to the rest of the molecule, to a first approximation, have about the same frequencies of vibration in any molecule. This makes it possible to associate a vibrational frequency with a particular chemical functional group, such as a carbonyl group or a phenyl ring, without considering the rest of the molecule. These general-purpose vibrational frequencies are called group frequencies. Tabulations of group frequencies are typically refined to include the small frequency shifts caused by properties of the rest of the molecule, such as a weakening of the oscillator bond strength due to electron density withdrawal by the rest of the molecule. Tabulations of characteristic frequencies also are specific to a type of vibrational spectroscopy, since vibrations that produce a strong signal with one type may produce little or no signal with a different type of vibrational spectroscopy.

Molecular vibrations are often classified into groups that are intuitively descriptive of the vibrational motion. An oscillation in bond length is called a “stretch.” An oscillation in bond angle is called a “deformation” or “bend.” More specialized descriptions include terms such as “wag,” “rock,” or “breathing mode.” Another way to classify molecular vibrations is by their symmetry properties using group theory. It can be shown that vibrations having certain symmetry properties will theoretically produce exactly zero signal for some types of spectroscopy, but not for other types of spectroscopy. Rules derived from symmetry considerations that identify vibrations expected to produce no spectroscopic signal are called selection rules. A detailed explanation of the use of group theory in vibrational spectroscopy is given in Refs 1 and 2.

1.3 Interactions Between Electromagnetic Radiation and Matter

1.3.1 Electromagnetic Radiation

Electromagnetic radiation consists of electric and magnetic fields oscillating in phase with each other and perpendicular to both each other and the direction of propagation. Gamma rays, X-rays, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, visible light, NIR and mid-IR radiation, terahertz (far-infrared) radiation, microwaves, and radio waves are all forms of electromagnetic radiation, differing only in their decreasing frequencies of oscillation. The energy of electromagnetic radiation is quantized. The smallest unit of light is the photon, having an energy, E, given by E = hυ, where υ is the frequency of the electromagnetic radiation and h is Planck's constant.

Electromagnetic radiation can be thought of either as a particle (photon) or as a wave. We will use the representation that is most intuitive when describing phenomena involving electromagnetic radiation. For simplicity, we will use the term “light” as synonymous with electromagnetic radiation of any frequency, rather than just those frequencies that are visible to the human eye.

Light travels at 2.99792458 × 108 m/s in a vacuum. The speed of light can be used to convert time into distance, thereby providing depth resolution. Raman, mid-infrared, and near-infrared spectroscopies have all been used this way to make three-dimensional chemical images of objects in the atmosphere, such as clouds or discharge plumes.

Light of a particular frequency can be specified by its wavelength (the distance light travels during one oscillation cycle of the electric field), its wavenumber (the number of oscillating cycles per centimeter), or its energy (e.g., Joules per photon). For example, light having a frequency of 6.00 × 1014 Hz has a wavelength of 500 nm, a wavenumber of 20,000 cm−1, and an energy of 3.98 × 10−19 J/photon, or 57.2 kcal/mol of photons.

Another important property of light is coherence. Coherence is a nonrandom relationship between photons. Coherence may be spatial (photon relationships based on photon location and/or direction) or temporal (relationships based on time when maxima in the oscillation fields of the photons occur). For example, a thermal light source is temporally incoherent because there is no mechanism coordinating the time that different photons are emitted. Lasers are temporally coherent because the process of stimulated emission causes the created photons to be in phase with the photons that stimulated the emission. Some spectroscopic processes such as coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS) or Raman gain spectroscopy rely on establishing temporal coherence between photons. Spectroscopic techniques such as FTIR (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) or OCT (optical coherence tomography) rely on establishing temporal coherence from nominally incoherent light sources.

1.3.2 Absorption and Emission of Light

A material having ...