- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Endocrinology and Diabetes

About this book

This brand new title in the Lecture Notes series covers a core element of the medical school curriculum.

It presents the basic science needed to understand mechanisms of disease and describes the clinical presentations of the disorders associated with different glands, concluding with the relevant investigations and management.

Focusing on conditions commonly encountered on the wards and in exams, with key points to aid revision and recall, this new title is perfect as a course companion and is the ideal revision tool for medical students, specialist nurses, and doctors working on endocrinology rotations. Lecture Notes: Endocrinology and Diabetes is also essential for endocrinology trainees approaching the new Knowledge Based Assessment (KBA).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Endocrinology and Diabetes by Amir H. Sam,Karim Meeran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Endocrinology & Metabolism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Thyroid anatomy and physiology

Anatomy

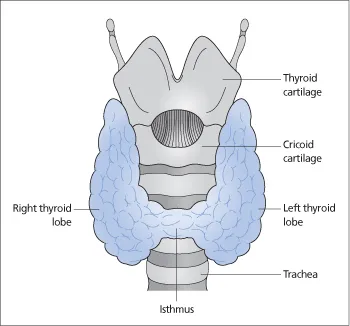

The thyroid gland consists of left and right lobes connected by a midline isthmus (Fig. 1.1). The isthmus lies below the cricoid cartilage, and the lobes extend upward over the lower half of the thyroid cartilage. The thyroid is covered by the strap muscles of the neck and overlapped by the sternocleidomastoids. The pretracheal fascia encloses the thyroid gland and attaches it to the larynx and the trachea. This accounts for the upward movement of the thyroid gland on swallowing.

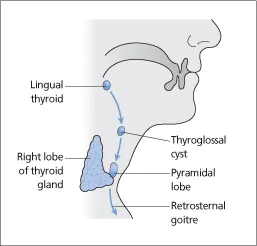

The thyroid gland develops from the floor of the pharynx in the position of the foramen caecum of the adult tongue as a downgrowth that descends into the neck. During this descent, the thyroid gland remains connected to the tongue by the thyroglossal duct, which later disappears. However, aberrant thyroid tissue or thyroglossal cysts (cystic remnants of the thyroglossal duct) may occur anywhere along the course of the duct (Fig. 1.2). Such thyroid remnants move upward when the tongue is protruded.

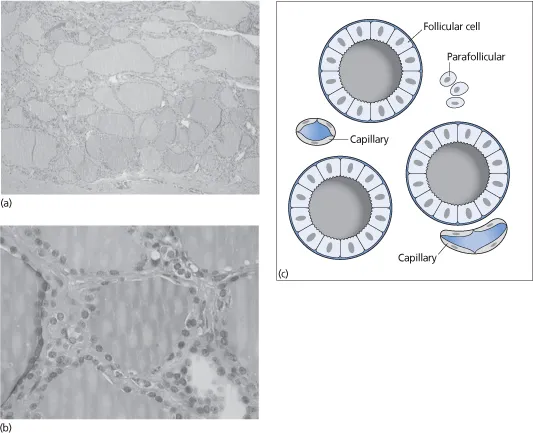

The thyroid gland is composed of epithelial spheres called follicles (Fig 1.3), whose lumens are filled with a proteinaceous colloid containing thyroglobulin. Two basic cell types are present in the follicles. The follicular cells secrete thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) and originate from a downward growth of the endoderm of the floor of the pharynx (see above). The parafollicular or C cells secrete calcitonin and arise from neural crest cells that migrate into the developing thyroid gland. The follicles are surrounded by an extensive capillary network.

Physiology

Thyroid hormones act on many tissues. They regulate:

- organogenesis, growth and development (central nervous system, bone)

- energy expenditure

- protein, carbohydrate and fat metabolism

- gut motility

- bone turnover

- heart rate and contractility, and peripheral vascular resistance

- beta-adrenergic receptor expression

- muscle contraction and relaxation

- the menstrual cycle

- erythropoiesis.

Iodine is essential for normal thyroid function. It is obtained by the ingestion of foods such as seafood, seaweed, kelp, dairy products, some vegetables and iodized salt. The recommended iodine intake for adults is 150 μg per day (250 μg per day for pregnant and lactating women). Dietary iodine is absorbed as iodide. Iodide is excreted in the urine.

Figure 1.1 Thyroid gland.

Figure 1.2 Possible sites of remnants of the thyroglossal duct.

Thyroid hormone synthesis

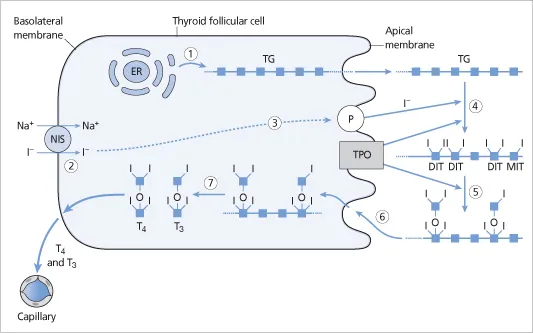

Figure 1.4 illustrates different steps in thyroid hormone synthesis:

- Thyroglobulin is synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and is transported into the follicular lumen by exocytosis.

- Iodide is transported into the thyroid follicular cells via a sodium–iodide symporter on the basolateral membrane of the follicular cells. Iodide transport requires oxidative metabolism.

- Inside the follicular cells, iodide diffuses to the apical surface and is transported by pendrin (a membrane iodide–chloride transporter) into the follicular lumen.

- Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) enzyme catalyzes the process of oxidation of the iodide to iodine and its binding (organification) to the tyrosine residues of thyroglobulin to form monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and diiodotyrosine (DIT).

- DIT and MIT molecules are linked by TPO to form thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) in a process known as coupling.

- Thyroglobulin containing T4 and T3 is resorbed into the follicular cells by endocytosis and is cleaved by lysosomal enzymes (proteases and peptidases) to release T4 and T3. T4 and T3 are then secreted into the circulation.

- Uncoupled MIT and DIT are deiodinated, and the free tyrosine and iodide are recycled.

Figure 1.3 (a) A low-power histological image of thyroid tissue showing numerous follicles filled with colloid and lined by cuboidal epithelium. (b) A high-power view of follicles lined by cuboidal epithelium. (c) Thyroid follicles (lined by follicular cells), surrounding capillaries and parafollicular cells.

The thyroid gland stores T4 and T3 incorporated in thyroglobulin, and can therefore secrete T4 and T3 more quickly than if they had to be synthesized.

Extra-thyroidal T3 production

T4 is produced entirely by the thyroid gland. The production rate of T4 is about 100 μg per day. However, only 20% of T3 is produced directly by the thyroid gland (by coupling of MIT and DIT). Around 80% of T3 is produced by the deiodination of T4 in peripheral extra-thyroidal tissues (mainly liver and kidney). The total daily production rate of T3 is about 35μg.

T4 is converted to T3 (the biologically active metabolite) by 5′-deiodination (outer-ring deiodination). 5′-Deiodination is mediated by deiodinases type 1 (D1) and type 2 (D2). D1 is the predominant deiodinating enzyme in the liver, kidney and thyroid. D2 is the predominant deiodinating enzyme in muscle, brain, pituitary, skin and placenta. Type 3 deiodinase (D3) catalyzes the conversion of T3 to reverse T3 (the inactive metabolite) by 5-deiodination (inner ring deiodination), as shown in Fig. 1.5.

Changes in T3 concentration may indicate a change in the rate of peripheral conversion and may not be an accurate measure of the change in thyroid hormone production. For example, the rate of T3 production (by 5′-deiodination of T4) is reduced in acute illness and starvation.

Total and free T4 and T3

Approximately 99.97% of circulating T4 and 99.7% of circulating T3 are bound to plasma proteins: thyroid-binding globulin (TBG), transthyretin (also known as thyroid-binding pre-albumin), albumin and lipoproteins.

Figure 1.4 Steps in thyroid hormone synthesis. (1) Thyroglobulin (TG) is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in the thyroid follicular cells and is transported into the follicular lumen. The small blue squares represent the amino acid residues comprising TG. (2) Iodide is transported into the follicular cell by the sodium–iodide (Na+/I−) symporter (NIS). (3) Iodide diffuses to the apical surface and is transported into the follicular lumen by pendrin (P). (4) Iodide is oxidized and linked to tyrosine residues in TG to form diiodotyrosine (DIT) and monoiodotyrosine (MIT) molecules. (5) Within the TG, T4 is formed from two DIT molecules, and T3 is formed from one DIT and one MIT molecule. (6) TG containing T4 and T3 is resorbed into the follicular cell by endocytosis. (7) TG is degraded by lysosomal enzymes to release T4 and T3 molecules, which move across the basolateral membrane of the follicular cell into the adjacent capillaries. TPO, thyroid peroxidase.

Only the unbound thyroid hormone is available to the tissues. T3 is less strongly bound and therefore has a more rapid onset and offset of action. The binding proteins have both storage and buffer functions. They help to maintain the serum free T4 and T3 levels within narrow limits, and also ensure continuous and rapid availability of the hormones to the tissues.

Free thyroid hormone concentrations are easier to interpret than total thyroid hormone levels. This is because the level of bound hormone alters with changes in the levels of thyroid-binding proteins, even though free T4 (and T3) concentrations do...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1: Thyroid anatomy and physiology

- Chapter 2: Hypothyroidism

- Chapter 3: Thyrotoxicosis

- Chapter 4: Goitre, thyroid nodules and cancer

- Chapter 5: Adrenal anatomy and physiology

- Chapter 6: Adrenal insufficiency

- Chapter 7: Primary hyperaldosteronism

- Chapter 8: Phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas

- Chapter 9: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Chapter 10: Adrenal incidentalomas

- Chapter 11: Pituitary anatomy and physiology

- Chapter 12: Pituitary tumours and other sellar disorders

- Chapter 13: Hypopituitarism

- Chapter 14: Hyperprolactinaemia

- Chapter 15: Acromegaly

- Chapter 16: Cushing’s syndrome

- Chapter 17: Diabetes insipidus

- Chapter 18: Hyponatraemia and syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion

- Chapter 19: Male reproductive physiology and hypogonadism

- Chapter 20: Gynaecomastia

- Chapter 21: Female reproductive physiology, amenorrhoea and premature ovarian failure

- Chapter 22: Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Chapter 23: Menopause

- Chapter 24: Hypocalcaemia

- Chapter 25: Hypercalcaemia and primary hyperparathyroidism

- Chapter 26: Osteomalacia

- Chapter 27: Osteoporosis

- Chapter 28: Paget’s disease of bone

- Chapter 29: Disorders of puberty

- Chapter 30: Growth and stature

- Chapter 31: Endocrine disorders of pregnancy

- Chapter 32: Neuroendocrine tumours

- Chapter 33: Obesity

- Chapter 34: Insulin and diabetes mellitus: classification, pathogenesis and diagnosis

- Chapter 35: Treatment of diabetes mellitus

- Chapter 36: Diabetic emergencies

- Chapter 37: Diabetic retinopathy

- Chapter 38: Diabetic nephropathy

- Chapter 39: Diabetic neuropathy

- Chapter 40: Musculoskeletal and dermatological manifestations of diabetes

- Index