![]()

PART 1

General Issues in Hyperkinetic Disorders

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Distinguishing Clinical Features of Hyperkinetic Disorders

Alberto Albanese1 and Joseph Jankovic 2

1 Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

2 Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic, Department of Neurology,Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

Introduction

Movement abnormalities can be dichotomized into the two broad categories of hypokinetic and hyperkinetic syndromes. The hallmark of hypokinesias is the loss of voluntary and automatic movements (akinesia), which is combined with slowness (bradykinesia) and stiffness or increased muscle tone (rigidity) in akinetic-rigid or parkinsonian syndromes [1]. In contrast, hyperkinesias are manifested by abnormal, uncontrollable, and unwanted movements. This term should not be confused with “hyperkinetic disorders” used in ICD 10 [2] to describe a behavioral abnormality – typically labeled attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity, occurring particularly in children and often associated with attention deficit and a tendency to move from one activity to another without completing any one. This is often associated with disorganized, ill-regulated, and scattered activity and thinking. This is not the only inconsistency between terminology in adult and childhood disorders, and efforts have been recently undertaken to unify the nosology and diagnostic recommendations in pediatric and adult movement disorders [3].

Hyperkinetic movement disorders include six main phenotypic categories, which can appear in isolation or in variable combinations: tremor, chorea, tics, myoclonus, dystonia, and stereotypies. In addition to these six categories there are other abnormalities of motor control that are also included within the field of movement disorders, such as akathisia, amputation stumps, ataxia, athetosis, ballism, hyperekplexia, mannerisms, myorhythmia, restlessness, and spasticity. The term “dyskinesia” is commonly used to indicate any or a combination of abnormal involuntary movements, such as tardive or paroxysmal dyskinesias or levodopa-induced dyskinesia, but more specific phenomenological categorization should be used whenever possible. In addition, there is a large and important group of peripherally-induced movement disorders, exemplified by hemifacial spasm [4], although any hyperkinetic movement disorder can be triggered or induced by peripheral injury [5].

Some conditions combine hypokinetic and hyperkinetic features, as exemplified by the coexistence of bradykinesia and tremor in Parkinson disease (PD) often referred to by the oxymora “gait disorder with acceleration” [6] or “shaking palsy” [7]. Probably the best examples of coexistent hyper- and hypokinesia is levodopa-induced dyskinesia in patients with PD and chorea or dystonia in patients with Huntington disease, many of whom have an underlying hypokinesia [8].

We describe here the hallmark features and phenomenology of the main hyperkinetic disorders, which are listed according to the time of their medical recognition.

Historical background

The importance of recognizing the appropriate phenomenology, not only as a guide to diagnosis but also as a means to study the pathophysiology of the disorder, is highlighted by the following statement attributed to Sir William Osler: “To study the phenomenon of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all” [9].

The characterization and classification of the various hyperkinetic disorders has evolved over a long period of time (Table 1.1). Tremor was a common language word before becoming a medical term. In ancient Greek, the root TRE is a lexical unit to indicate at the same time fear and shaking. Tremor was defined by Galen as an “involuntary alternating up and down motion of the limbs.” Involuntary movements present during action or at rest were also mentioned by Sylvius [10]. Parkinsonian tremor was later described by James Parkinson [7] and further differentiated from kinetic “intentional tremor” by Charcot [11]. The familial occurrence of postural action tremor was recognized shortly afterwards [12].

Epidemics of “dancing mania” emerged in central Europe in the late Middle Ages as local phenomena [13] or in connection with pilgrimages. Coincident with the Black Plague in 1348–50, St Vitus was called upon to intercede, leading to the term “chorea Sancti Viti” (St Vitus dance) to indicate at the same time a request for intercession and a means to expiate. This terminology has entered medical literature after Paracelcus described this syndrome among one of the five that “deprive man of health and reason.” He adopted the term “chorea” into medical jargon and proposed using the expression “chorea lasciva” to describe the epidemics [14]. One century later, Thomas Sydenham observed an epidemic affecting only children which he called “chorea minor” [15] and was later recognized to be a manifestation of rheumatic fever. Adult-onset hereditary chorea was described in the 19th century [16] and later renamed Huntington chorea.

Table 1.1 Chronology of first description of the main hyperkinetic disorders.

|

| Ancient Greece | Tremor | τρεμω (to tremble, to fear) |

| XI Century | Chorea | Choreomania (ritual dance) |

| XVII Century | Tic | French horse breeders |

| 1871 | Athetosis | Hammond [71] |

| 1881 | Myoclonus | Friedreich [21] |

| 1885 | Ballism | Kussmaul [72] |

| 1911 | Dystonia | Oppenheim [24] |

| 1953 | Asterixis | Adams [23] |

The term “tic” arose in France in the 17th century to describe shivers in horses, particularly of certain breeds, which affect primarily the muscles of the pelvic region, pelvic limbs, and tail [17]. The word was later used by French doctors by analogy. The first medical report on human tics is probably the description of the Marquise of Dampierre, who started having tics at 7 years of age [18]. Later, Trousseau listed tics among choreatic disorders [19] and Gilles de la Tourette provided a separate taxonomic categorization of these phenomena [20].

Essential myoclonus was first described by Friedrich [21], who reported a 50-year-old man with a 5-year history of multifocal muscle jerks affecting both sides of the body symmetrically, but asynchronously. The syndrome was defined as “paramyoclonus multiplex” because of the reported symmetry. Forms of myoclonic epilepsy were later described and Lundborg [22] proposed a classification of myoclonus that remains largely in use today. Asterixis was observed in patients with hepatic encephalopathy [23] and later recognized to be a form of negative myoclonus.

Dystonia was the last main hyperkinetic disorder to be recognized: its name derives from a supposed alteration of muscle tone in patients with generalized distribution [24]. The hereditary nature was noted at about the same time [25].

Phenomenology and classification

Although at first sight involuntary movements resemble each other, each hyperkinetic disorder has a specific phenomenology (signature) that can be identified by direct observation of the patient or videotaped examination. Duration, rhythmicity, topography, and other features must be carefully analyzed and noted in order to make a specific phenomenological diagnosis [26] (Table 1.2).

Tremor

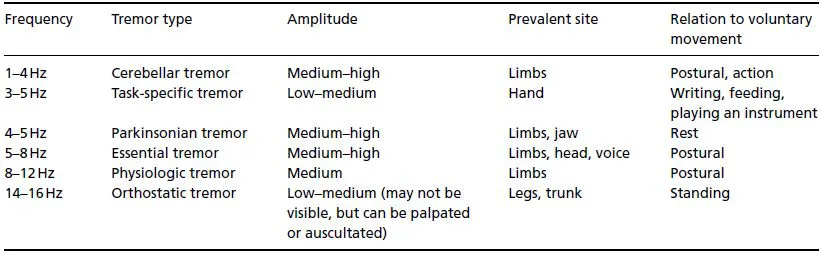

Tremor is an involuntary, rhythmic, oscillation of a body region about a joint axis. It is usually produced by alternating or synchronous contractions of reciprocally innervated agonistic and antagonistic muscles that generate a relatively symmetric velocity in both directions about a midpoint of the movement [27, 28]. The oscillation produced by tremor can be represented by a sinusoidal curve; it is generated by rhythmical discharges in an oscillating neuronal network and maintained by feedback and feed-forward loops. The resulting movement is patterned and rhythmic, characteristics that distinguish tremor from other hyperkinesias [29].

Tremor varies when different voluntary movements are performed or postures are held: it is labeled as a rest tremor, postural tremor, or action tremor according to the condition of greatest severity. Intention tremor, typically associated with cerebellar dysfunction, is characterized by the worsening of tremor on approach to a target, as in a finger-to-nose maneuver. The typical rest tremor of PD has a frequency of 4 to 6 Hz, and is most prominent distally. Its characteristic appearance in the hand is also referred to as a pill-rolling tremor. Parkinsonian rest tremor also typically involves the chin, jaw, and legs, but almost never involves the neck. Indeed, head oscillation should suggest essential tremor or dystonic tremor rather than PD. True rest tremor, however, disappears during complete rest, such as sleep, and is reduced or disappears with voluntary muscle contraction, or during movement. Postural tremor is present with the maintenance of a particular posture, such as holding the arms outstretched in front of the body. It is commonly seen in physiological and essential tremor. Re-emergent tremor refers to a postural tremor that occurs after a variable latency period during which time no observable postural tremor is present [30]. This typically occurs in the setting of PD, and most likely represents a parkinsonian rest tremor that has been “reset” during the maintenance of a posture [31].

Task-specific tremor occurs only during execution of a particular task, such as writing, and is considered by many to be a variant of dystonic tremor. Dystonic tremor may occur in the setting of dystonia, and is a rhythmic, oscillation-like, dystonic movement [32]. Position-specific tremors only occur when the affected body part is placed in a particular position or posture. Orthostatic tremor is an example of a position-specific tremor, and refers to a fast (14–16 Hz) tremor, mainly affecting the trunk and legs, that occurs after standing for a certain period of time [33].

Chorea

Chorea is an irregular, unpredictable, involuntary random-appearing sequence of one or more, discrete, involuntary jerk-like movements or movement fragments. Movements appear random due to the variability in timing, duration, direction, or anatomic location. Each movement may have a distinct start and end point, although these may be difficult to identify since movements are often strung together, one immediately following or overlapping another. Movements may, therefore, appear to flow randomly from one muscle group to another, and can involve trunk, neck, face, tongue, and extremities. Infrequent and mild chorea may appear as isolated, small-amplitude brief movements. It may resemble restless, fidgety, or anxious behavior. When chorea is more severe, it may appear to be almost continuous, flowing from one site of the body to another (Figure 1.1).

Although chorea may be worsened by movement, it usually does not stop with attemp...