Neuroscience of Cognitive Development

The Role of Experience and the Developing Brain

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Neuroscience of Cognitive Development

The Role of Experience and the Developing Brain

About this book

A new understanding of cognitive development from the perspective of neuroscience This book provides a state-of-the-art understanding of the neural bases of cognitive development. Although the field of developmental cognitive neuroscience is still in its infancy, the authors effectively demonstrate that our understanding of cognitive development is and will be vastly improved as the mechanisms underlying development are elucidated. The authors begin by establishing the value of considering neuroscience in order to understand child development and then provide an overview of brain development. They include a critical discussion of experience-dependent changes in the brain. The authors explore whether the mechanisms underlying developmental plasticity differ from those underlying adult plasticity, and more fundamentally, what distinguishes plasticity from development. Having armed the reader with key neuroscience basics, the book begins its examination of the neural bases of cognitive development by examining the methods employed by professionals in developmental cognitive neuroscience. Following a brief historical overview, the authors discuss behavioral, anatomic, metabolic, and electrophysiological methods. Finally, the book explores specific content areas, focusing on those areas where there is a significant body of knowledge on the neural underpinnings of cognitive development, including:

* Declarative and non-declarative memory and learning

* Spatial cognition

* Object recognition

* Social cognition

* Speech and language development

* Attention development

For cognitive and developmental psychologists, as well as students in developmental psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive development, the authors' view of behavioral development from the perspective of neuroscience sheds new light on the mechanisms that underlie how the brain functions and how a child learns and behaves.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Brain Development and Neural Plasticity

A Précis to Brain Development

BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

| Developmental Event | Timeline | Overview of Developmental Event |

| Neurulation | 18–24 prenatal days | Cells differentiate into one of three layers: endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm, which then form the various organs in the body. The neural tube (from which the CNS is derived) develops from the ectoderm cells; the neural crest (from which the ANS is derived) lies between the ectodermal wall and the neural tube. |

| Neuronal migration | 6–24 prenatal weeks | Neurons migrate at the ventricular zone along radial glial cells to the cerebral cortex. The Neurons migrate in an inside-out manner, with later generations of cells migrating through previously developed cells. The cortex develops into six layers. |

| Synaptogenesis | 3rd trimester–adolescence | Neurons migrate into the cortical plate and extend apical and basilar dendrites. Chemical signals guide the developing dendrites toward their final location, where synapses are formed with projections from subcortical structures. |

| These connections are strengthened through neuronal activity, and connections with very little activity are pruned. | ||

| Postnatal neurogenesis | Birth–adulthood | The development of new cells in several brain regions, including: |

| —Dentate gyrus of the hippocampus | ||

| —Olfactory bulb | ||

| —Possibly cingulated gyrus; regions of parietal cortex | ||

| Myelination | 3rd trimester–middle age | Neurons are enclosed in a myelin sheath, resulting in an increased speed of action potentials. |

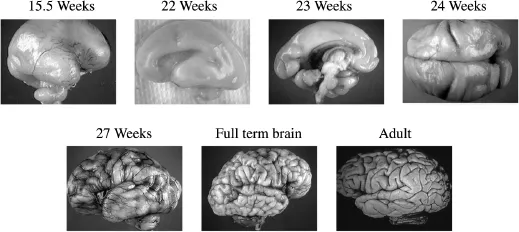

| Gyrification | 3rd trimester–adulthood | The smooth tissue of the brain folds to form gyri and sulci. |

| Structural development of the prefrontal cortex | Birth–late adulthood | The prefrontal cortex is the last structure to undergo gyrification during uterine life. The synaptic density reaches its peak at 12 months, however, myclination of this structure continues into adulthood. |

| Neurochemical development of the prefrontal cortex | Uterine life–adolescence | All major neurotransmitter systems undergo initial development during uterine life and are present at birth. Systems do not reach full maturity until late adulthood. |

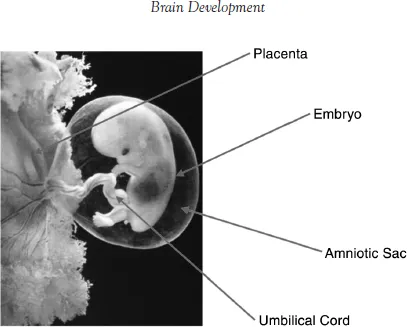

Embryonic Origins of Brain Tissue

STAGES OF BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

Neural Induction and Neurulation

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Why Should Developmental Psychologists Be Interested in the Brain?

- Chapter 1: Brain Development and Neural Plasticity

- Chapter 2: Neural Plasticity

- Chapter 3: Methods of Cognitive Neuroscience

- Chapter 4: The Development of Speech and Language

- Chapter 5: The Development of Declarative (or Explicit) Memory

- Chapter 6: The Development of Nondeclarative (or Implicit) Memory

- Chapter 7: The Development of Spatial Cognition

- Chapter 8: The Development of Object Recognition

- Chapter 9: The Development of Social Cognition

- Chapter 10: The Development of Higher Cognitive (Executive) Functions

- Chapter 11: The Development of Attention

- Chapter 12: The Future of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience

- References

- Index