- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In order to bring a character to life, it is beneficial for animators to have a solid understanding of acting principles, and this book examines the important skills behind the artistry of creating animated characters. With a particular emphasis on a character's motions and movement, this unique resource covers the basic elements of acting for CG animation and then progresses to more advanced topics such as internal intent and motivation.

Note: CD-ROM/DVD and other supplementary materials are not included as part of eBook file.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

What Is Acting?

Acting is defined as the art or practice of representing a character on a stage or before cameras and derives from the Latin word agere, meaning “to do.” When someone is acting, they are performing an action: thus, something is being done as a character. Generally an actor is someone who takes on another character by altering parts of their body, voice, or personality in order to share a story with an audience. Ironically, or perhaps appropriately for this book, an obsolete meaning for the word acting is to animate.

In regard to CG animation and your work in this book, the definition seems perfect: If actors are animating a character, then CG animators are acting as they create. What exactly actors do and how they do it has changed over time. What was acceptable and what was preferred has varied radically throughout history.

This chapter discusses:

• A brief history of acting

• How acting has changed over time

• The work of an actor

• How an actor trains

• How acting relates to the animator

• Exercises to begin your journey of exploring the training of an actor

A Brief History of Acting

Similar to many noted animated tales, the history of acting begins with a legend. During the sixth century in ancient Greece, a man named Thespis stepped out of a chorus of performers to utter several solo lines, and thus acting was born. Prior to this time, if you went to a dramatic festival in Greece you would see a group of 50 performers singing or chanting in unison the tales of Greek gods or heroes. When Thespis first spoke, he assumed a character and told the story from the character’s point of view, not from a third person as was done by the chorus. Although this is only a legend, Thespis has been granted a special place in the history of acting, and to this day actors are called thespians.

Jon Lovitz brought the word thespian to the forefront of popular culture with his character, Master Thespian, on Saturday Night Live.

Eventually, in ancient Greece the number of actors grew to three and were accompanied by a chorus. Although often more than three characters took part in a play, only three of the characters could appear on the stage at any one time, as there were only three actors. Thus one actor would often play more than one role in any given production. They would change characters with a change of costume and mask.

Given the nature of the large, outdoor amphitheatres that the Greeks performed in, and the emphasis placed on the ritual of theatre, the work of the first actors was predominately voice and gesture work (see Figure 1.1). The actors, all men, were dressed in large robes that covered their bodies and oversized masks that hid their faces so that the actor/ character could be seen at a great distance. They communicated character and emotion through changes in the voice and in the physical stature of their bodies.

Unlike actors in ancient Greece, who were revered, it is believed the actors in ancient Rome were slaves owned by company managers. The performances were still outdoors and masks were still used, so much of the work of actors remained focused on the voice and gesture. There was no restriction on the numbers of actors in Roman theatre, but they still were all men. The dramatic material also went through a great transformation in Rome. The stories of the Greeks were of their heroes and gods. The stories of ancient Rome were often of everyday life and could be quite licentious.

The late Roman empire was the first period where Christianity began to target theater, and actors in particular. Theater was associated with pagan festivals and could often be vulgar. Mimes of the time even went so far as ridiculing Christian practices such as baptism and communion. By AD 300, Christians were told not to attend the theater, and any Christian who went to the theater instead of the church on a holy day was excommunicated. Actors were not allowed to partake of the sacraments or be buried in church cemeteries. During the rise of the Christian period, theaters declined and almost completely disappeared. Traveling jugglers, mimes, storytellers, and acrobats who could be seen at fairs carried on the performance traditions.

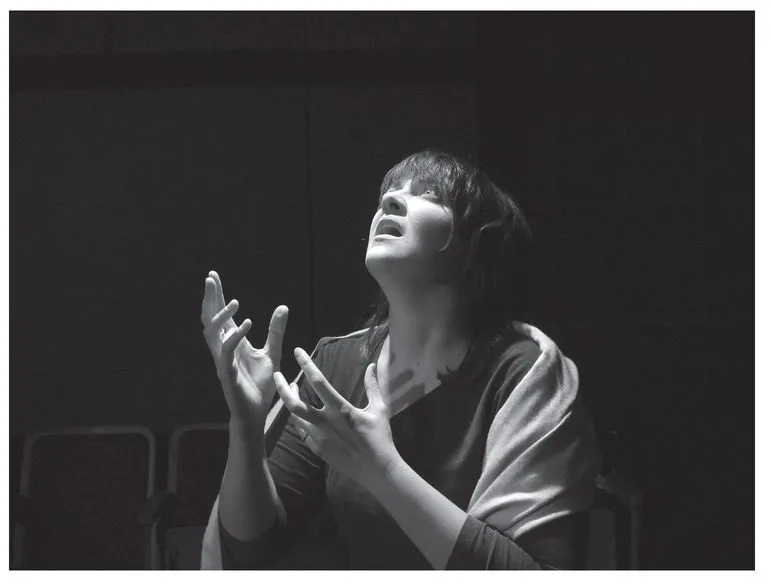

Figure 1.1 Amy Roeder plays Hecuba in a scene from Trojan Women at the University of Georgia Department of Theatre and Film Studies, directed by George Contini

The Middle Ages

It is ironic that after all the opposition by the church to theater, the church is the very place where theater was revived during the Middle Ages. During an Easter service in AD 925, a performance that was probably sung depicted the three Marys looking for Jesus at his tomb and encountering angels that proclaim him to be risen from the dead. This was the beginning of liturgical drama where clergy and choirboys performed biblical stories and moral lessons as part of the church services. There was no real emphasis on acting here; the importance of the event was the didactic lessons that were learned, not artistic merit.

Eventually the popularity of these performances led to the development of theater outside the church. Although the scripts were still approved by the church, trade and craft guilds took over the production of plays. Actors for these productions were local towns-people. Sometimes they received their roles by auditioning, and sometimes they merely volunteered. The scripts were stereotypical with one-dimensional characters and thus did not require any subtlety of acting. Once again the most important aspect of the performance was the voice and stylized gesture.

Commedia dell’Arte

During the Renaissance, most theatrical productions moved to the court and were performed by courtiers. This theater was more for showing off than any real acting. The development of a professional, public theater happened in Italy with the rise of Commedia dell’Arte, an improvised form of theater based on stock characters and scenarios. Each member of an acting troupe had a specific character they performed. The scripts were completely improvised from plot synopses developed by the troupe in rehearsal. Commedia was at its height between 1570 and 1650.

A Commedia actor would take on a character and perform this character for her or his entire life. All of the stock characters had masks that were specifically designed to show the qualities of the character, and the performers had certain physical gestures or comic bits called lazzi that were associated with the mask and character (see Figure 1.2). The work was highly physical and demanded a great deal of vocal and physical control, power, and stamina. Commedia also introduced women to the stage. However, the characters were stock types and the situations were stereotypical, so there still was no need for subtly of acting. Instead, the emphasis was placed on the physical and vocal work as well as a quick wit to be able to improvise the scenarios.

Figure 1.2 The University of Georgia Commedia troupe

Commedia laid the groundwork for characters that we still use today in theater, film, and animation. The “dirty old man,” the “braggart solider,” the “sneaky servant,” the “empty-headed young lover,” and the “licentious servant” are all character types that we recognize in our comedies. These and almost all stock types can be traced back to Commedia. (For more on Commedia, see Chapter 4, “Commedia dell’Arte.”)

Acting in Shakespeare’s Day

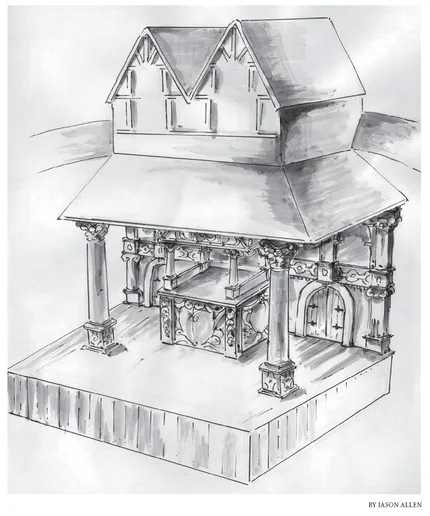

In 1570, the Queen of England sanctioned daily theatrical performances, and consequently many acting troupes were formed in England. Actors were shareholders in their companies and were paid by a member of the royal family who served as their patron. A shareholding actor had to invest a sum of money in the company and then shared in any profits that were made from the performances. One of the most famous troupes was The King’s Men—William Shakespeare himself was a member of this company. (See Figure 1.3.)

Figure 1.3 Drawing of the stage of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre

There are many different opinions concerning the acting style of the Elizabethan performer. Some descriptions of performances have called them realistic. Hamlet’s advice to the players would suggest that the Elizabethan actors understood the ground rules for producing a psychologically realistic character on the stage. On the other hand, men playing women, stylized stage backgrounds, and the unrealistic nature of many of the scripts suggest that the actor was still focused on the external voice and gesture of the character. In either case, audience members have written accounts of the actors moving audiences emotionally by the power of their performances.

Hamlet: Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounc’d it to you, trippingly on the tongue. But if you mouth it, as many of our players do, I had as lief the town crier spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air too much with your hand, thus, but use all gently; for in the very torrent, tempest, and (as I may say) whirlwind of your passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness. O, it offends me to the soul to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings…, Suit the action to the word, the word to the action; with this special observance, that you o’erstep not the modesty of nature: for anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ’t were, the mirror up to nature; to show Virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.

— HAMLET ACT III, SCENE II

During the 1640s, England was embroiled in a civil war between the Royalists and the Puritans. The Puritans attempted to end all theatrical activity because they had returned to the early Christians’ beliefs concerning the theater and actors. In 1642, a law was passed suspending all performances, and five yea...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dear Reader

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 - What Is Acting?

- CHAPTER 2 - Foundations of Animation

- CHAPTER 3 - Stanislavski’s System

- CHAPTER 4 - Commedia dell’Arte

- CHAPTER 5 - Bioenergetics

- CHAPTER 6 - Using the Work of Michael Chekhov in Animation

- CHAPTER 7 - Essences

- CHAPTER 8 - Laban Effort Analysis

- CHAPTER 9 - Alba Emoting

- CHAPTER 10 - The Voice and Voice-Over Acting

- CHAPTER 11 - Creating Lip Sync and Facial Performance for Voiced Characters

- APPENDIX - About the Companion DVD

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Action! by John Kundert-Gibbs,Kristin Kundert-Gibbs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Digital Media. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.