eBook - ePub

Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Etiology and Assessment of Behavior Problems

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Etiology and Assessment of Behavior Problems

About this book

Handbook of Applied Dog Behaviour and Training, Volume two: Etiology and Assessment of Behaviour Problems is the definitive reference for dog trainers, behaviourists, breeders and veterinarians. Coupled with Volume one, this text provides theoretical and practical framework for understanding the development and treatment of dog behaviour problems.

Topics covered include Fear, anxiety and phobias, Separation-related problems, Hyperactivity, and Dominance, territorial, and fear-related aggression.

The focus is to present and evaluate the relevant applied and scientific literature, and to highlight what remains to be learned, while the author introduces alternative ways for analysing and understanding the etiology of dog behaviour problems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Etiology and Assessment of Behavior Problems by Steve Lindsay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Veterinary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

History of Applied Dog Behavior and Training

To his master he flies with alacrity, and submissively lays at his feet all his courage, strength, and talent. A glance of the eye is sufficient; for he understands the smallest indications of the will. He has all the ardour of friendship, and fidelity and constancy in his affections, which man can have. Neither interest nor desire of revenge can corrupt him, and he has no fear but that of displeasing. He is all zeal and obedience. He speedily forgets ill-usage, or only recollects it to make returning attachment the stronger. He licks the hand which causes pain, and subdues his anger by submission. The training of the dog seems to have been the first art invented by man, and the fruit of that art was the conquest and peaceable possession of the earth.

G. L. L. COMTE DE BUFFON, quoted in JACKSON (1997)

Social Parallelism, Domestication, and Training

Cave Art and the Control of Nature

Evolution of Altruism and Empathy

Dogs and the Ancient World

Roots of Modern Training

European Influences

Famous Dogs

American Field Training

Organized Competitive Obedience

Dogs and Defense

War Dogs

After the War

Vietnam and Dog Training

The Monks of New Skete

New York and the North American Society of Dog Trainers

Science and Behavior

Applied Dog Behavior

Contemporary Trends in Dog Training

References

OUR SPECIES is the only one that keeps and purposefully modifies the behavior of another species to make it a more compatible and cooperative companion and helper. The process of domestication involves at least three interdependent elements: (1) selective breeding for conducive traits, (2) controlled socialization with their keepers, and (3) systematic training to obtain desirable habits. In addition to the effects of selective breeding, socialization, and training, a dog’s basic needs are largely provided by a human caregiver. The overall effect of domestication is to perpetuate paedomorphic characteristics into adulthood and to enhance a dog’s dependency on its keeper for the satisfaction of its biological and psychological needs, including affection and a sense of belonging to a group. The origins of this process began far back into prehistoric times.

SOCIAL PARALLELISM, DOMESTICATION, AND TRAINING

Close social interaction between early humans and dogs was probably facilitated by the evolution of parallel social structures, especially the tendency to form cooperative hunting groups and extended families. Both wolves and early humans shared sufficient similarity of social custom to communicate well enough to lay a foundation and bridge for the development of a lasting relationship. One possible scenario is that early humans coming out of Africa approximately 140,000 years ago encountered wolves dispersed throughout the Eurasian land mass. These early humans, perhaps numbering only a few hundred individuals, are believed to have beeen the direct ancestors of contemporary humans. Over a relatively short period, these migrant humans were able to supplant indigenous humans already living in Eurasia. In Evolving Brains, John Allman (1999) speculates that the primary advantage needed to achieve this biological precedence and hegemony may have been the domestication of wolves. According to this view, the two species were preadapted to fit each other’s ecology and family structure, thus making the transition to domestication relatively easy and natural. By cooperating, the two species may have attained an enormous competitive advantage over other species competing for the same resources. Interestingly, the migration out of Africa by this small group of humans roughly coincides with the first evidence of domestication as indicated by the analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences. These studies indicate that the domestication of dogs was probably initiated approximately 135,000 years ago (Wayne and Ostrander, 1999). To fully exploit the advantages presented by domestication, early humans must have developed relatively sophisticated means of behavioral control and training. Undoubtedly, our ancestors engaged in activities aimed at limiting some sorts of dog behavior while encouraging other forms as opportunities and needs may have presented themselves. The obvious necessity of training as an integral part of the domestication process prompted Comte de Buffon to conclude that dog training was the first art invented by humans (see the introductory epigraph). Whether dog training was the first art will remain the subject of debate; however, one can safely assume that dog training, in one form or another, emerged long before the advent of recorded history.

Cave Art and the Control of Nature

Clearly, early humans were acute observers and sensitive social organizers, living in close-knit and cooperative hunting-gatherer groups. That they were interested in animal habits and their control is attested to by the masterful cave paintings found at Altamira (Spain) and Lascaux (France). These artworks were produced at about the same time that dogs began to appear in the archeological record, between 12,000 to 17,000 years ago (Jansen, 1974). The paintings depict with extraordinary sensitivity and realism a procession of various prey animals (e.g., bison, and deer) captured in line and color and transfixed in time to await rediscovery after many millennia shrouded in darkness. The animals are beautifully rendered in moments of flight or after falling from mortal wounds inflicted on them by the artist-hunter. The purpose of this early art was presumably to exert magical control over the prey animal by capturing its image and “killing” it, thereby giving the hunter success during the chase. One can hardly imagine that the Magdalenian people responsible for cave painting had not also discovered other means of control besides sympathetic magic, just as they had certainly learned how to use many natural forces long before they had names or adequate means to describe them.

Evolution of Altruism and Empathy

The ancient emergence of dog keeping appears to coincide with the evolutionary appearance of altruism and empathy among humans. According to Eccles (1989), the likely foundation of human altruism is the emergence of food sharing, followed closely by the development of the nuclear family and extended family groups. As humans evolved into food-sharing communities composed of individuals cooperating with one another, the emerging tendency toward altruism may have been extended to semidomesticated canids living at the outermost perimeter of their encampments. These early canids also appear to have evolved significant altruistic tendencies and social structures, perhaps sufficient to attract empathic interest by early humans, if not to mediate symmetrical altruistic reciprocation and exchange. Eccles characterizes altruistic actions as purposeful efforts intended to benefit others without regard to how they might benefit oneself. He rejects Dawkins’s (1976) more severe definition in which altruism denotes actions that benefit another at some expense or sacrifice to the altruistic actor. Eccles appears to assume that the advent of human altruism entailed an awareness of self and empathy for others. As a result of such evolutionary elaborations and social developments, altruistic humans may have been prompted to feel sympathy and pity for dogs living and suffering in their midst, thereby facilitating a growing sense of commonality and responsibility toward dogs.

Early training activities probably included the contingent sharing of food based on dogs behaving in some particular way (e.g., begging). The power of empathy would have offered early humans the ability to consider how their actions might influence dogs. In fact, the development of human empathy and its extension to dogs provides a viable means for understanding how the evolutionary gap between our two species was narrowed sufficiently to enable close interspecies cohabitation and domestication. Human altruism, coupled with empathy for others (especially those belonging to a common group that are acted toward altruistically), may have provided the foundation for the dog’s domestication and behavioral incorporation. Human altruism and empathy seem to be especially strong toward the young, perhaps explaining the evolutionary trend toward paedomorphosis in dogs (see Paedomorphosis in Volume 1, Chapter 1). Paedomorphic dog types may have enjoyed a significant survival advantage by evoking altruistic caregiving and protective behavior in human captors.

DOGS AND THE ANCIENT WORLD

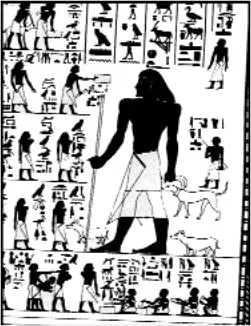

The earliest historical records of dogs come mainly from the art of Egypt and Assyria (Merlin, 1971). Archeological findings suggest that at least a dozen different breeds existed in ancient Egypt, ranging from the greyhound-like coursing hound and mastifflike hunting dogs to dogs resembling the modern dachshund. Egyptian hunters primarily used coursing hounds that were slipped to chase down fleeing game. Egyptian breeders selected for traits and structural attributes conducive to this sort of hunting activity, as well as short-legged dogs, perhaps, used for digging into burrows after fleeing animals (Figure 1.1). As such, all breeding is a form of antecedent control over behavior that is subsequently refined and brought into practical expression by the agency of training. As remains common today, the breeding and training of dogs were probably overseen by the same person.

FIG. 1.1 Egyptian hunters developed a variety of breeds for different tasks, ranging from the sleek coursing hounds to short-legged dogs that may have been used for chasing prey to earth. (Detail from an Egyptian tomb painting, Beni Hasan, 1900 B.C.)

By the time Herodotus visited Egypt in the mid-5th century B.C., the dog was found living in homes as companions. When house dogs and cats died, the household experienced a period of mourning. The dead animals were mummified and given ritual burials. Other evidence of highly developed breeding and training practices comes from Assyrian basrelief depictions of powerful mastiffs used for various hunting purposes (Figure 1.2). Unfortunately, details from this period are lacking with respect to the methods of training used, but there can be little doubt that training played an important role in the way such dogs were prepared for the hunt and to live in close contact and harmony with humans.

FIG. 1.2 Large mastiff-type dogs were used by Assyrian hunters to hunt large prey. Note the early use of slip collars. Assyrian dogs also wore bronze collars shaped in the form of a spiralling ring (Assyrian basrelief, 7th-century B.C.).

As suggested by Homer’s verses describing the sorrow felt by Odysseus for his dying dog Argos (“Swift”), Greek dogs were held as objects of sincere affection and symbols of devotion and faithfulness (see Dog Devotion and Faithfulness in Volume 1, Chapter 10). However, the Greek attitude toward dogs was complex, with many common expressions of contempt and personal insult involving reference to dogs. By the 5th century B.C., various dog breeds had been developed for specific hunting tasks and other purposes, such as guarding and shepherding flocks. In addition to working dogs, the Greeks also kept household or “table” dogs and small Melitean lapdogs as pets (Halliday, 1922). The breeding and training of hunting dogs appear to have been significant pastimes for ancient Greeks. Xenophon (circa 380 B.C.), a student of Socrates, wrote a valuable tract on dog husbandry and training entitled Cynegeticus (Hull, 1964; Merchant, 1984; see Xenophon, 1925/1984a), which gives the reader a rare glimpse into the breeding and management of Greek hunting dogs. For hunting hare, Xenophon recommends the Castorian and vulpine breeds, the latter of which was believed to be the result of an admixture of dog and fox lineage—a false belief that was widely accepted at the time. Aristotle perpetuated the vulpine-cross belief in his History of Animals and further suggested that the Indian hound (a particularly aggressive variety) was the result of crossing a male tiger with a female dog. These Indian hounds (mastiff-type dogs) were used for deer hunting and other pursuits that required bigger and stronger breeds. For wild boar, a variety of dogs were employed in a mixed pack, including the Indian, Cretan, Locrian, and Laconian breeds. Apparently, great care was taken to keep these breeds unadulterated. Control over undesirable matings was discouraged by the use of a spiked surcingle, or girth strap, that was wrapped around the female dog’s body (Hull, 1964). However, Merlin (1971) has suggested that another possible function of this piece of equipment was to protect the dog from injury when hunting dangerous game like wild boar.

Xenophon recognized the value of early training and recommended that a dog’s education be started while it was still young and most eager to learn. During the early stages of training, hare-hunting dogs were trained to drive fleeing prey into snag nets by feeding the dogs near the location of the nets, at least until they developed a sufficient appetite for the hunt itself to perform the task of coming to the nets without such aid. Young trailing dogs were placed on long leashes and paired up with more experienced dogs to hunt hare. As their training progressed, novice dogs were restrained until the hare was out of sight and then released to ensure that they relied on scent rather than sight to follow and locate the fleeing prey. If a puppy failed to trail an animal in the correct direction, the puppy was recalled and the procedure repeated until the behavior ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 History of Applied Dog Behavior and Training

- 2 Behavioral Assessment

- 3 Fears and Phobias

- 4 Attachment, Separation, and Related Problems

- 5 Excessive Behavior

- 6 Aggressive Behavior: Basic Concepts and Principles

- 7 Intraspecific and Territorial Aggression

- 8 Social Competition and Aggression

- 9 Appetitive and Elimination Problems

- 10 Cynopraxis

- Index