![]()

SECTION 1

An Introduction to the Technology of Training

Chapter 1: The Technology of Training

Provides an overview of the instructional systems design (ISD) process and introduces the four basic components of all training programs: the content, the objectives, the instructional methods, and the delivery media.

Chapter 2: An Introduction to Structured Lesson Design

Introduces the general structure of a lesson and the content-performance matrix. Provides the rationale for documenting the key instructional methods in the learning materials.

![]()

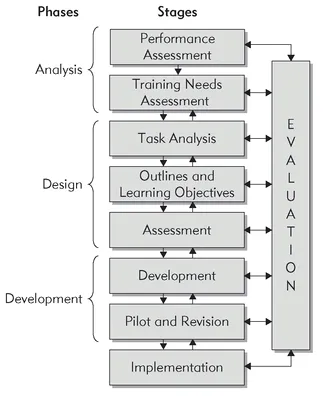

Figure 1.I. An Instructional Systems Design (ISD) Process

1

The Technology of Training

AN INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

An economy dependent on design, engineering, analysis, and service—in other words on knowledge work—cannot afford ineffective or inefficient training. Training with organizational payoff won’t happen by accident. It requires a systematic approach to analyze requirements, define instructional ingredients, and create a learning environment that achieves your goals. This systematic approach is called Instructional Systems Design or ISD for short. The result of ISD is the definition of four main ingredients in your training program: instructional content, learning outcomes, instructional methods, and delivery media.

This book is about the processes and guidelines you need to develop technical training that is consistent and effective. I define technical training as learning environments delivered in face-to-face classrooms or via computer designed to build job-relevant knowledge and skills that improve bottom-line organizational performance.

The Costs of Training Waste

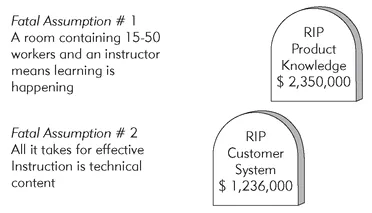

It’s a common and costly myth that if there are ten to fifty people in a room with an “instructor” at the front showing slides and talking, learning is taking place. In other words, a training “event” is assumed to result in learning. It is further assumed that learning translates into improved job performance. Another pervasive myth suggests that training delivered on a computer is not as effective as face-to-face learning. Whether delivered in a classroom or on a computer, often training events fail to realize their potential! Participants are unable to do anything new or different after training when they return to the job. Or if they can do new and different things, those things don’t translate into job skills that align to bottom-line organizational objectives. In fact, some studies have shown that learners were better off before the training than afterward, when they felt confused and inadequate about their own abilities.

Exact estimates of training waste are difficult, since training results are so rarely measured that no one really knows for sure what has—or has not—been accomplished. Only about 50 percent of companies measure learning outcomes from training, and less than a fourth make any attempt to assess job transfer or work improvement resulting from training (Sugrue & Rivera, 2005).

The costs of ineffective training are twofold. First, there are the visible dollars invested in instructors, training materials, and training administration. This is not a trivial sum. The annual Training magazine industry survey reports that in 2006 over $56 billion were invested by U.S. organizations in training (Industry Report, 2006). And this is a low estimate because it does not include the most expensive element of any training program—the time workers spend in training events. When training funds are not well invested, the result is waste—not only of the training expenditures, but also from lost-opportunity costs of a workforce that lacks the skills they need to fully utilize the technologies or techniques required by their jobs.

A typical lost-opportunity scenario is associated with the development and installation of a new software system. Months, even years, of effort and hundreds of thousands of dollars are invested in the design and development of the software. Then, sometimes almost as an afterthought, someone is asked to put together a training package for the end users. Because the resulting training is suboptimal, the software ends up underutilized and a portion—sometimes a substantial portion—of the system potential is never realized. Some new users ask for help from their colleagues in adjacent cubes. Others spend hours poring over confusing technical manuals. The immediate result is learning and performance that is inconsistent and inefficient. The long-term result is underutilized and mis-utilized software.

I write this book for individuals with technical training assignments who may be new training specialists or technical experts with an instructional assignment. As job performance become increasingly knowledge-based, there is a growing and appropriate trend toward using technical experts as trainers. But this brings us to another costly training myth: the misconception that all it takes for effective training is technical expertise, combined with the years most of us spent in formal educational programs. This assumption puts an unfair burden on the experts, who are not given adequate support in the preparation and delivery of their training. It is also unfair to the employees who are supposedly “trained” and later feel demoralized because they can’t apply the skills needed on their jobs. Finally, poor training cheats the organization by failing to generate a return on investment. These two assumptions are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Why We Can’t Afford Ineffective Technical Training

Five major trends make the development of the human resource through effective training a greater priority than in the past:

1. New Technology: Organizations continue to be increasingly dependent on the use of new technologies, especially information technologies, as routine business tools. While many tools have improved user interfaces over the past ten years, in many cases new functionality goes unexploited in terms of productivity payoff.

Figure 1.1. Two Fatal Assumptions About Training That Lead to the Graveyard of Lost Business Opportunity

2. A Knowledge-Based Workforce: Knowledge workers have nearly doubled in the last half of the 20th century from 37 percent in 1950 to nearly two-thirds of total employment in 2000 (Wolff, 2005). Reliance on a skilled workforce continues to grow in industries most dependent on safety, knowledge, and service. In 2005 the industry segments with highest per employee expenditures on training were transportation and utilities; finance, insurance, and real estate; and services (Sugrue & Rivera, 2005).

3. Lifelong Learning: An aging population requires organizations to think now about how to efficiently transfer a large skill reserve to replace a growing number of retirees. At the same time, new products, global competitors, updated policies, and emerging markets require a flexible workforce that can rapidly acquire and apply new skills. Lifelong learning requires continuous and rapid deployment of effective instructional resources.

4. Access to Learning Resources: The ubiquitous access to data via broadband Internet and wireless technologies makes channels of instruction broadly available to a wide population. Similarly, many workplace tools such as new software systems embed training and memory support within the tool itself. However, as we will see below, it is not the delivery medium that impacts instructional effectiveness. Only by using effective instructional methods can we harness delivery channels effectively.

5. Operational Alignment: In a global economic environment, learning must be aligned to business strategy and increasingly integrated into the work environment. Better decisions about how to deploy training resources will result in growth of “just-in-time” performance support resources and smarter use of formal training events that will be integrated as one element of larger performance improvement initiatives.

In the 21st century, the development of the human resource can no longer receive less than top priority in any organization determined to remain competitive. In fact, in a knowledge economy the emphasis shifts from traditional capital resources to the human resource for competitive edge.

If you are a technical expert, you are already a valuable resource for your skills and knowledge. But learn to transmit your expertise to others effectively and efficiently and you quadruple your value. If you are a new training specialist you will add value by learning to elicit knowledge and skills from experts and to organize and display that content in ways that lead to efficient learning and performance by the workforce. Follow the guidelines in this book and your training will enable the workforce to fully utilize the skills you teach and to feel more confident about their work tasks. Furthermore, if you follow my guidelines for measuring training outcomes, you will know—not just guess at—your training results.

What Is Technical Training?

Some interpret the term technical training as meaning “hard skills,” such as using a new computer system or applying safety standards during equipment operations. I define technical training as “

a structured learning environment engineered to improve workplace performance in ways that are aligned with bottom-line business goals.” This definition includes five main elements:

1. Structured—An effective training environment is designed to optimize learning both during the training event and afterward on the job. Following a structured process and producing a structured product minimizes inconsistency in learning environments and aligns instructional products to job-essential knowledge and skills.

2. Environment—Workforce learning is moving from a series of isolated training events to environments that incorporate diverse knowledge resources such as repositories of examples, performance templates, and access to expertise, along with traditional events in face-to-face and virtual media.

3. Engineered—Effective learning environments do not happen by accident or by seat-of-the pants efforts. Effective learning environments are the products of a structured process and proven instructional methods matched to your content.

4. Workplace Performance—An effective training program starts and ends with the job. It includes guidelines, examples, and exercises that are job relevant.

5. Business Goals—An effective training program focuses on knowledge and skills that are aligned to important organizational objectives. Rather than training “communication skills,” an effective learning design defines specific behaviors associated with the types of communications needed to support organizational objectives.

Technical training includes both hard and soft skills. It incorporates on-the-job performance support as well as training events—delivered in classrooms and on computers. Note that I emphasize training as a process rather than an event. Too often training is conceived and implemented as a discrete event with a beginning and end. Instead of “classes,” consider learning as an ongoing process that can be engineered to include both traditional leader-led instruction in face-to-face or virtual classrooms as well as asynchronous activities and resources scheduled before, between, and after more traditional events.

Some important skill requirements such as management skills or skills associated with widespread computer programs can be achieved with “off-the-shelf” prepackaged training materials. However, many job tasks are unique to a given industry, organization, or department. No off-the-shelf training exists to meet these needs. It is this training that will be developed by or under the supervision of each organization’s training staff. Industry-specific training runs the gamut from specialized computer systems to customer communication...