![]()

PART One

Bubbles and Crises: The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Setting the Stage for Financial Meltdown

INTRODUCTION

In this first chapter we outline in basic terms the underlying mechanics of the ongoing financial crisis facing the financial services industry, and the challenges this creates for future credit risk models and modelers.

Rather than one crisis, the current financial crisis actually comprises three separate but related phases. The first phase hit the national housing market in the United States in late 2006 through early 2007, resulting in an increase in delinquencies on residential mortgages. The second phase was a global liquidity crisis in which overnight interbank markets froze. The third phase has proved to be the most serious and difficult to remedy and was initiated by the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. The lessons to be learned for credit risk models are different for each of these phases. Consequently, we describe first how we entered the initial phase of the current crisis. In the upcoming chapters, we discuss the different phases and implications of the global financial crisis that resulted from the features that characterized the run-up to the crisis.

THE CHANGING NATURE OF BANKING

The traditional view of a bank is that of an institution that issues short-term deposits (e.g., checking accounts and certificates of deposit) that are used to finance the bank’s extension of longer-term loans (e.g., commercial loans to firms and mortgages to households). Since the traditional bank holds the loan until maturity, it is responsible for analyzing the riskiness of the borrower’s activities, both before and after the loan is made. That is, depositors delegate the bank as its monitor to screen which borrowers should receive loans and to oversee whether risky borrowers invest loan proceeds in economically viable (although not risk-free) projects see Diamond [1984].

In this setting, the balance sheet of a bank fully reflects the bank’s activities. The bank’s deposits show up on its balance sheet as liabilities, whereas the bank’s assets include loans that were originated by the bank and are held to maturity. Despite the simplicity of this structure, traditional banking is not free of risk. Indeed, the traditional model tended to expose the bank to considerable liquidity risk, interest rate risk, and credit risk. For example, suppose a number of depositors sought to withdraw their deposits simultaneously. In order to meet depositors’ withdrawals the bank would be forced to raise cash, perhaps by liquidating some assets. This might entail the selling of illiquid, long-term loans at less than par value. Thus, the bank might experience a market value loss because of the liquidity risk associated with financing long-term, illiquid assets (loans) with short-term, readily withdrawable liabilities (deposits).

With respect to interest rate risk in the traditional banking model, a good example occurred in the early 1980s when interest rates increased dramatically. Banks and thrift institutions found that their long-term fixed-rate loans (such as 30 year fixed-rate mortgages) became unprofitable as deposit rates rose above mortgage rates and banks earned a negative return or spread on those loans.

The traditional banking model has always been vulnerable to credit risk exposure. Since traditional banks and thrifts tended to hold loans until maturity, they faced the risk that the credit quality of the borrower could deteriorate over the life of the loan.

In addition to the risk exposures inherent in traditional banking, regulatory requirements began to tighten in the late 1980s and early 1990s. For example, the Basel I capital regulations requirement (the so-called 8 percent rule) set risk-based capital standards that required banks to hold more capital against risky loans and other assets (both off and on the balance sheet). Capital is the most expensive source of funds available to banks, since equity holders are the most junior claimants and are viewed as the first line of defense against unexpected losses. When the risk of losses increases and additional capital is required, the cost of bank funds increases and bank profitability falls.

As a result, the traditional banking model offered an insufficient return (spread) to compensate the bank for assuming these substantial risk exposures. Consequently, banks increasingly innovated by creating new instruments and strategies in an attempt to reduce their risks and/or increase their returns. These strategies are of much relevance in understanding the first (credit crisis) phase of the 2007-2009 crisis. Most important among these strategies were: (1) securitization of nonstandard mortgage assets; (2) syndication of loans; (3) proprietary trading and investment in non-traditional assets, such as through the creation of hedge funds; and (4) increased use of derivatives like credit default swaps to transfer risk from a bank to the market at large.

Securitization

Securitization involves a change in strategy from a traditional bank’s policy of holding the loans it originates on its balance sheet until maturity. Instead, securitization consists of packaging loans or other assets into newly created securities and selling these asset-backed securities (ABSs) to investors. By packaging and selling loans to outside parties, the bank removes considerable liquidity, interest rate, and credit risk from its asset portfolio. Rather than holding loans on the balance sheet until maturity, the originate-to-distribute model entails the bank’s sale of the loan and other asset-backed securities shortly after origination for cash, which can then be used to originate new loans/assets, thereby starting the securitization cycle over again. The Bank of England reported that in the credit bubble period, major UK banks securitized or syndicated 70 percent of their commercial loans within 120 days of origination.1 The earliest ABSs involved the securitization of mortgages, creating collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs).

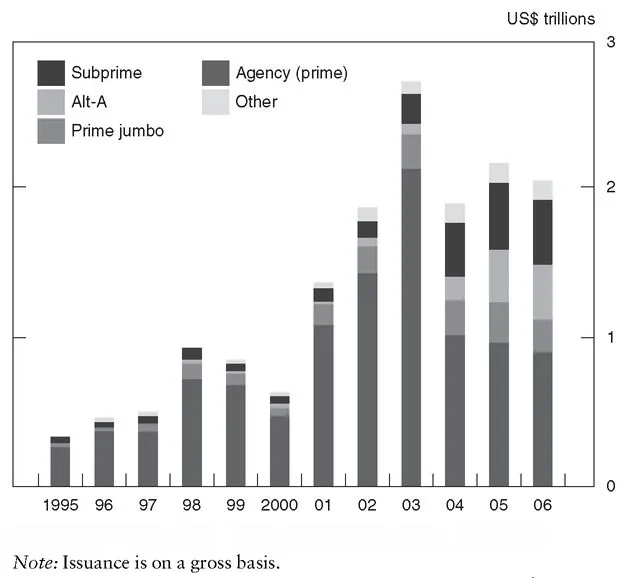

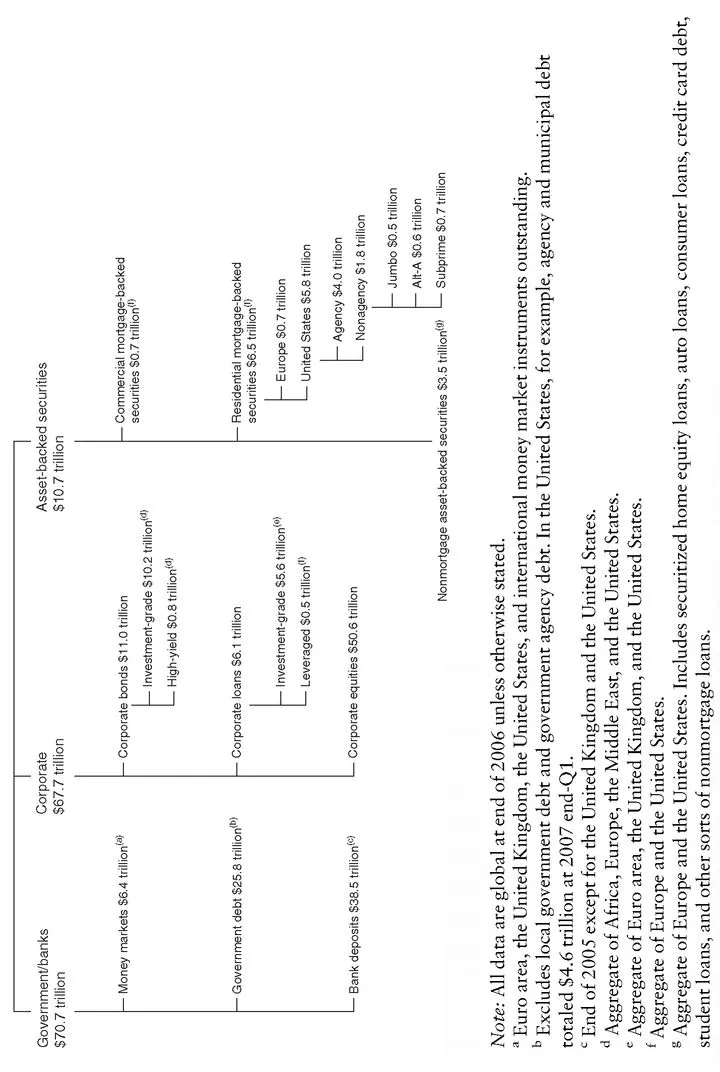

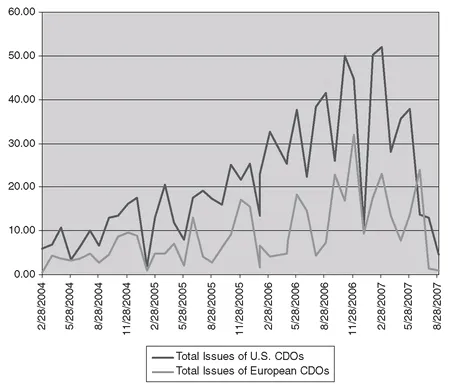

The market for securitized assets is huge. Figure 1.1 shows the explosive growth in the issuance of residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBSs) from 1995 to 2006, in the period just prior to the 2007-2009 crisis. Indeed, Figure 1.2 shows that, as of the end of 2006, the size of the RMBS market exceeded the size of global money markets. While the markets for collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were smaller than for RMBS, they had also been rapidly growing until the current crisis.2 Figure 1.3 shows the volume of CDO issuance in Europe and the United States during the 2004 through September 2007 period. The three-year rate of growth in new issues from 2004 through 2006 was 656 percent in the U.S. market and more than 5,700 percent in the European market.

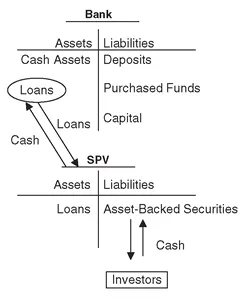

The basic mechanism of securitization is accomplished via the removal of assets (e.g., loans) from the balance sheets of the banks. This is done by creating off-balance-sheet subsidiaries, such as a bankruptcy-remote special-purpose vehicle (SPV, also known as special-purpose entity, or SPE) or a structured investment vehicle (SIV). Typically, the SPV is used in the more traditional form of securitization. In this form, a bank packages a pool of loans together and sells them to an off-balance-sheet SPV—a company that is specially created by the arranger for the purpose of issuing the new securities. 3 The SPV pools the loans together and creates new securities backed by the cash flows from the underlying asset pool. These asset-backed securities can be based on mortgages, commercial loans, consumer receivables, credit card receivables, automobile loans, corporate bonds (CDOs), insurance and reinsurance contracts (Collateralized Insurance Obligations, CIOs), bank loans (CLOs), and real estate investment trust (REIT) assets such as commercial real estate (CRE CDOs).

FIGURE 1.1 U.S. Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities Issuance

Source: Bank of England, Financial Stability Report no. 22, October 2007, page 6.

Figure 1.4 illustrates this traditional form of securitization. The SPV purchases the assets (newly originated loans) from the originating bank for cash generated from the sale of ABSs. The SPV sells the newly created asset-backed securities to investors such as insurance companies and pension funds. The SPV also earns fees from the creation and servicing of the newly created asset-backed securities. However, the underlying loans in the asset pool belong to the ultimate investors in the asset-backed securities. All cash flows are passed through the SPV and allocated according to the terms of each tranche to the ultimate investors.4 The SPV acts as a conduit to sell the securities to investors and passes the cash back to the originating bank. The ABS security investor has direct rights to the cash flows on the underlying assets. Moreover, the life of the SPV is limited to the maturity of the ABS. That is, when the last tranche of the ABS is paid off, the SPV ceases to exist.

FIGURE 1.2 Size of Global Securities Markets

Source: Bank of England, Financial Stability Report no.22, October 2007, page 20.

FIGURE 1.3 U.S. and European CDO Issuance 2004-2007

Source: Loan Pricing Corporation web site, www.loanpricing.com/.

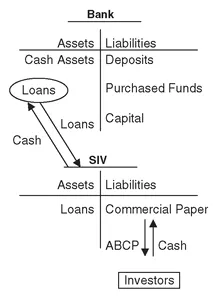

While this method of securitization was lucrative, financial intermediaries soon discovered another method that was even more lucrative. For this form of securitization, an SIV is created. In this form, the SIV’s lifespan is not tied to any particular security. Instead, the SIV is a structured operating company that invests in assets that are designed to generate higher returns than the SIV’s cost of funds. Rather than selling the asset-backed securities directly to investors in order to raise cash (as do SPVs), the SIV sells bonds or commercial paper to investors in order to raise the cash to purchase the bank’s assets. The SIV then holds the loans purchased from the banks on its own balance sheet until maturity. These loan assets held by the SIV back the debt instruments issued by the SIV to investors. Thus, in essence the SIV itself becomes an asset-backed security, and the SIV’s commercial paper liabilities are considered asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP).

FIGURE 1.4 The Traditional Securitization Process

Figure 1.5 shows the structure of the SIV method of asset securitization. Investors buy the liabilities (most often, asset-backed commercial paper) of the SIV, providing the proceeds for the purchase of loans from originating banks. The SIV’s debt (or ABCP) is backed by the loan or asset portfolio held by the SIV. However, the SIV does not simply pass through the payments on the loans in its portfolio to the ABCP investors. Indeed, investors have no direct rights to the cash flows on the underlying loans in the portfolio; rather, they are entitled to the payments specified on the SIV’s debt instruments. That is, the SIV’s ABCP obligations carry interest obligations that are independent of the cash flows from the underlying loan/asset portfolio. Thus, in the traditional form of securitization, the SPV only pays out what it receives from the underlying loans in the pool of assets backing the ABS.

In the newer form of securitization, the SIV is responsible for payments on its ABCP obligations whether the underlying pool of assets generates sufficient cash flow to cover those costs. Of course, if the cash flow from the asset pool exceeds the cost of ABCP liabilities, then the SIV keeps the spread and makes an additional profit. However, if the assets in the underlying pool do not generate sufficient cash flows, the SIV is still obligated to make interest and principal payments on its debt instruments. In such a situation the SIV usually has lines of credit or loan commitments from the sponsoring bank. Thus, ultimately, the loan risk would end up back on the sponsoring bank’s balance sheet.5

FIGURE 1.5 A New Securitization Process

Because of the greater expected return on this newer form of securitization, it became very popular in the years leading up to the financial crisis. Whereas an SPV only earns the fees for the creation of the asset-backed securities, the SIV also earns an expected spread between high-yielding assets (such as commercial loans) and low-cost commercial paper as long as the yield curve is upward-sloping and credit defaults on the asset portfolio are low. Indeed, because of these high potential spreads, hedge funds owned by Citicorp and Bear Stearns and others adopted this investment strategy. Until the 2007-2009 crisis, these instruments appeared to offer investors a favorable return/risk trade-off (i.e., a positive return) and an apparently small risk given the asset-backing of the security.

The balance sheet for an SIV in Figure 1.5 looks remarkably similar to the balance sheet of a traditional bank. The SIV acts similarly to a traditional bank—holding loans or other assets until maturity and issuing short-term debt instruments (such as ABCP) ...