![]()

Chapter 1

Big Neck, Virginia

Joe Hill grew up in Big Neck, an old textile town of 20,000 people in the rolling flat lands and gentle blue hills of rural Piedmont Virginia. Once, maybe a century ago, the mills had offered jobs and a measure of prosperity, but Big Neck was too far from Washington, Charlottesville, and Richmond to have benefited from their fancy suburban sprawl, and the mills now struggled along with light manufacturing and electronics. The railroad still ran through the center of town, but the heavy freight trains just thundered through on their way to somewhere else. American prosperity had more or less casually, thoughtlessly passed Big Neck by, and the population was down from 35,000 a quarter of a century ago.

Big Neck was integrated, hardworking, stalled, middle America. There was nothing upwardly mobile about it, but the town functioned. The climate was mild, the schools were decent, and, all things considered, it wasn’t a bad place to grow up in. Although it wasn’t a small town, everybody knew a lot about you by the time you had lived there for 10 years or were 13 years old. You had a public history, which maybe was Dolores’s problem.

Dolores was Joe’s mother. She was white. Joe’s dad, Big Joe, as he was called, was black. Their son was the result of a high school romance, conceived by accident just after graduation. The pair lived together after Joe’s birth in a rented dingy row house on Elm Street, separately but amicably enough when whatever magic there once was, wore off. In the years that followed, Big Joe and Dolores were distantly friendly, held within a tenuous orbit by their mutual love for their son.

Little Joe was a big strong baby who would stand in his playpen and violently shake the railing, laughing and yelling at the same time. Big Joe’s friends were impressed. “Joe, that boy is going to be a banger,” they would say. “That kid is going to be all muscle and fight.”

Big Joe was a foreman in the mill. He was a large, contemplative, handsome mahogany-colored man whom people looked up to and who didn’t waste a lot of words on idle chatter. “The first screw to get loose in your head,” Big Joe liked to say, “is the one that holds your tongue in place.” A couple of years after his split with Dolores, he married a black woman and they had three girls. Joe’s half sisters idolized him and frantically competed for his attention.

Despite his second family, Big Joe was involved in his son’s upbringing. On his way home from work, he would drop by before dinner most evenings. Since Big Joe was a good natural athlete, he encouraged his son to play sports and, as the boy grew up, they ran pass patterns on a field down the street and played one-on-one basketball in the driveway. When the mild southern Virginia weather cooperated, they played golf. About once a week, you could find the two of them out on the scruffy municipal golf course lugging their old bags over the bedraggled, wandering links. There were pullcarts available for three dollars, but they always carried their bags.

“Makes no sense for us to pay six dollars between us when we got strong backs and like the exercise,” Big Joe would tell his son. “Besides, we ain’t long on money.”

By the time he was 12, Joe could outdrive his father and hit a golf ball nearly 300 yards. But his favorite sport was football. Football was—and is—the big sport in the mill towns of rural Virginia, and Joe played his way up through the Midget and Peewee leagues. His father was one of the youth league coaches, and he never missed a game or practice. Never! Yet, during these games, Big Joe discovered that within Joe’s seemingly happy-go-lucky, well-adjusted personality burned a fierce competitive fire. Sometimes Big Joe worried about this intensity. The boy concealed it from others, but one day after his team lost a Peewee game, the 12-year-old boy kicked the stuffing out of the backseat of his father’s aging car. Big Joe made him pay for the repairs, once again saying: “We ain’t long on money, son. Best you learn now that temper tantrums are expensive.”

Joe was also an obsessive perfectionist; he could not bear to lose in a one-on-one basketball game or on the golf course. A muffed golf shot would cause Joe to pound the offending club against a tree, and a lost father-son basketball game would send him sulking, silently furious, back into the house. Although Joe got mad, he worked hard at practicing so that he could do better the next time.

As for Dolores, life seemed to have passed her by. She worked long hours as a waitress. Though in the early years she dated other men, she never married. As she aged, she became thick around the waist and lost her looks. Her face became pale and pinched, her eyes dark and anxious, and her hair stringy. She didn’t appear to be a happy person. There was a certain unspoken, lugubrious bitterness in her attitude as though she sensed she had been ostracized.

Subconsciously, Dolores worried that her son’s biracial background was a disadvantage and her worry made her feel guilty. She focused on Joe, but he grew secretly ashamed of her as he grew older and she became less predictable. Once as a young boy, on a soft, golden October afternoon, Joe was gang tackled during a Peewee football game. The play ended with Joe at the bottom of a pile of aggressive boys. Suddenly, Dolores detached herself from the cluster of other parents standing on the far sideline and bolted across the field screaming, “Leave him alone,” and then began pulling the other boys away.

Years later, Joe would recount that suspended moment—when he was imprisoned at the bottom of the pile under the brilliant, windless sky of early autumn—as perhaps the most mortifying moment of his life.

Yet, Dolores made some important contributions to Joe’s childhood. Forced to listen to three televisions blaring endlessly in the tavern where she worked, she insisted on minimal television at home.

In fact, the only time TV was permitted was when a sporting event was on or Big Joe came to visit. Father and son would watch sports in Dolores’s congested, high-ceilinged living room, which was dominated by a sagging couch on a gray carpet stained with 20 years of footprints and spilled soft drinks. Dust motes reeled in the shafts of sunlight as they watched games there, sunken into two stuffed armchairs, while Big Joe explained the complexities and nuances of football, basketball, and baseball. At these moments, Joe felt like he was part of a real family. It was as close as they ever came to a communion.

But, as soon as the game was over, Big Joe would leave and Dolores would insist that Joe turn off the television and read a book. She loved to read and she was determined that her son would be an educated man. “You gotta be somebody,” she would tell him. “You gotta be smart; you gotta make money; you gotta get out of here.” Listening to her, he didn’t discard her exhortations. Joe understood, albeit dimly, her dissatisfaction with the monotony of her life, and early on he knew he wanted something better—a lot better. But it seemed as though the fastest, easiest way out of Big Neck and into money was through sports.

In an effort to combine Joe’s love of sports with his education, Dolores gave him a card football game called Running Back on Christmas day. The game and its statistics became his obsession. He created a league with two divisions of four teams and stocked them with players from the actual National Football League. Then he played endless games and kept detailed statistics for each quarterback, running back, and receiver. The mathematics of quarterback ratings and yards gained after the catch were complex, and he became engrossed with the analysis of the statistics and the ebb and flow of his players’ careers. Running Back was the beginning of his interest in numbers and the message within them.

As Joe played his way up through the age groups in the youth sport leagues in town, it became apparent that he was by far the best athlete of his age in town. Big and strong, he was superbly coordinated and almost preternaturally fast.

By the time he entered junior high, Joe was a lean, handsome, dark-complexioned boy whose biracial background was apparent. He had learned at age nine from an older boy’s snide comment that he was a mulatto, a half-breed from an unwanted pregnancy, but after he gave the boy a bloody nose, no one ever mentioned it again—at least not to his face. Nevertheless, it was always with him although he never spoke of it. Was he white, he wondered, or was he black? Which crowd should he naturally hang out with or did he have entree to both?

He eventually came to realize, however, that outside of Big Neck, the rest of the world viewed him as black because of his dark complexion. When he came into contact with the outside world, he couldn’t go around with a sign on his back affirming that he was half-white. Nor did he want to. In fact, as time went on, if anything, he became prouder of his blackness than his whiteness. Partially, he recognized, this was because he was more comfortable with his father than with his mother.

Nevertheless, Joe was a socially, athletically, and intellectually confident boy. Schoolwork came easily to Joe, so easily that Dolores considered taking him out of the Big Neck public school system and sending him to St. David’s, the Jesuit Catholic school in town, which was considerably more rigorous academically. Big Joe objected, not because of the religious conversion that a scholarship would entail, but because the athletic program at St. David’s was weak.

In junior high school, Josh Gibson noticed Joe. Gibson’s family had lived in Big Neck forever, and he and his older brother owned the mill where Big Joe worked. Gibson lived five miles from town on a 200-acre spread of rolling land with several hundred beef cows, and by Big Neck standards he was immensely rich. The mill was very profitable, and everyone knew he was the biggest customer of the Merrill Lynch office on Third Street. He was perhaps 40; a bald, heavyset man. His belly bulged over his belt, his neck bulged over his collar, and his eyes bulged out of an open, friendly face. He was as affable as the day was long. He was married but without children, and he genuinely cared about kids, the town, and his employees at the mill, but above all, he loved jocks and sports.

Gibson had always liked Big Joe, and he began to hear chatter on the mill floor that Big Joe had a kid who was some kind of a super athlete. In the fall of 1983, Gibson had gone to one of his Peewee League football games, and as he got to know the boy he came to like him more and more. He recognized Joe’s intelligence, and he was particularly intrigued with Joe’s statistical bent with numbers and with Running Back. As Gibson listened to Joe talk about Running Back, the boy’s natural reserve evaporated. Gibson and Joe shared a love of numbers.

But Gibson also cared about the land, his land. He was easily moved to quote Robert Frost’s lines “the land was ours before we were the land’s” which meant, he explained to Joe, that a man had to physically work his land to have the land accept him. There was a tract of 50 acres that had once been part of his farm with an old mill that lay between his place and the river. “My place is lopsided without it,” he would tell Joe. He yearned for it. “The corn in that bottom is doing right well. That was always good ground for corn. No better on the river.”

Joe was with him the afternoon the owner of the parcel sent word he would sell. He would experience the elation on Gibson’s face, and that evening observe how Gibson went into the twilight to gaze down at the fields, the dark green mass by the river, that was now his land. They later would walk through the grove of cedars to the disintegrating structure of the old mill; the stone dam hung with moss. At night, the motionless water above the mill looked like slick, black metal.

Joe fell in love with that piece of land. From the river, it swept away to the hills and the sky. It was thick and green and beautiful. During summers he worked for Gibson one summer clearing brush and another rebuilding the stonework on the dam. It was hard, manual labor and he relished it. At noon he would eat his sandwiches up on the meadow and then roll over on his stomach and inhale the land. He loved the rich, fragrant odor of the black earth and the grass. Years later, when the financial plague came, the feel of the land, the work, and the smell of the soil saved his sanity and maybe his life.

Gibson also harbored a secret fascination with the stock market. Like Joe, he loved to pore over statistics and valuations. As the year passed, and they became almost kindred spirits, Gibson began to jabber at Joe about his stock ideas. His mill was a supplier to Wal-Mart and he was intrigued with the company and its lean modus operandi. He bought the stock in early 1982 and hung on to it.

On a Saturday in May of 1984 Gibson took both Joes out to lunch at McDonald’s. When they had settled into a booth, Gibson said, “Look, son, I know you’re a good athlete, but even more important, I think you’re a smart young guy with a fascination and gift for numbers. The stock market is numbers and brains and intuitions. I want to get you interested in it, so you know what? I’m going to give you 15 shares of Wal-Mart. The stock closed at $31.40 yesterday so that’s like $470, but I want you to promise me you won’t sell it for two years. After that you can do what you want with it and the money. Is it a deal?”

Big Joe looked puzzled and Little Joe looked stunned.

“That’s real generous of you, Mr. G,” Big Joe said. “But tell me again why you’re doing this.”

“Plain and simple. I want to get this man-boy of yours interested in the stock market, and not just football, and I think Wal-Mart is going up and that’ll get his attention.”

“Mr. G, you know I want to play in the NFL someday,” Joe said.

“Yeah, I know that and I’m rootin’ for you. But I want you to use those big muscles in your head and not just the ones in your legs and arms. Will you agree to the deal?”

Joe looked at his father, who nodded. Then he replied: “Yeah, of course I will. It’s the first money I’ve ever had, and you’re right, I’ll watch it real close. You’ve showed me how to look up stock prices before. Guess I’ll have to ask Mom to bring home her restaurant’s copy of the Richmond Post Reporter.”

“Okay,” said Gibson. “I’ll open an account for you at Merrill Lynch on Monday morning. I’m going to tell them to send you the same research they send me. And I’m going to tell my guy there to keep his mouth shut about this.”

“Should be interesting,” said Big Joe. “Only stock I ever owned is Virginia Electric & Power and it’s been a dog.”

“Well, Wal-Mart ain’t no dog,” said Gibson with a big grin. “It’s a hungry tiger.”

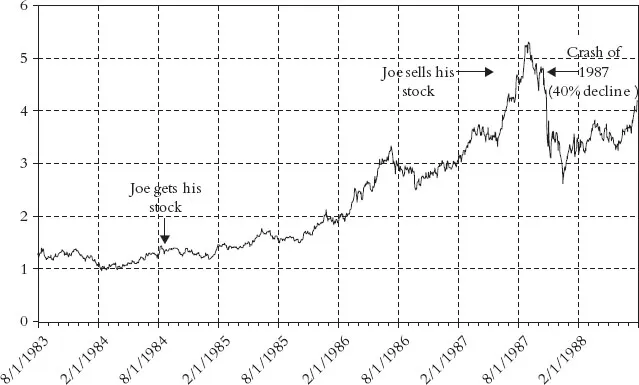

And that’s how it began. Joe followed the stock’s progress. As Figure 1.1 shows, Wal-Mart’s shares soared and by July of 1987, the stock was selling in the $90s. (Note, price data have been adjusted for subsequent stock splits.)

Gibson had never had such a winner, and at that price he sold out his position. Joe followed him; after all, he said to himself, “What do I know?” But the money certainly got his attention. When Gibson told him about the capital gains tax, he was appalled at the Internal Revenue Service’s share of the profits. Nevertheless, it felt marvelous to have $1,350 in the bank, and he began to think about finding another stock. Maybe, he thought, I have a magic touch.

His elation faded as the stock kept climbing throughout the summer of 1987, touching 106. Then, to his astonishment, came The Crash of 1987, and at one point Wal-Mart hit 56. In the long run, though, the Cr...