![]()

CHAPTER 1

Edging Toward Violence and Chaos

Crude oil may rise to between $150 and $200 a barrel within two years as growth in supply fails to keep pace with increased demand from developing nations, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts led by Arjun N. Murti said in a report. . . . “The possibility of $150-$200 per barrel seems increasingly likely over the next six to twenty-four months, though predicting the ultimate peak in oil prices as well as the remaining duration of the upcycle remains a major uncertainty,” the Goldman analysts wrote in the report dated May 5.

—“Goldman’s Murti Says Oil ‘Likely’ to Reach $150-$200”

Nesa Subrahmaniyan, Bloomberg, May 6, 2008

In 2008, the price of oil had risen so dramatically that it dominated the global conversation and the global media. The inexorable increase in the price of gas at the pump threatened to destabilize the global economy. Fuel prices were forcing the world to spend a disproportionate portion of its income not only on fuel but also on grain as alternative-energy products displaced foodstuff agriculture.

The solutions proposed so far—from “gas-tax holidays” to presidential requests to the Saudis to increase supply—have been only Band-Aids, not long-term solutions, and the proposed reasons for rising oil prices have been controversial: Was it the Arabs, acting as a greedy cartel? Was it the 2 billion Chinese and Indians whose burgeoning middle classes were placing unsustainable demands on scarce supplies? Was it some sort of satanic lobbying on the part of big Western oil companies against alternative-energy programs? Was it Wall Street speculators? What would the inflated oil prices do to economies already nearly down for the count from the subprime credit crisis?

The West was slow to see the warning signs of the oil-price run-up. As late as September 2003, when prices were less than $25 a barrel, Americans rarely exhibited any interest in oil. The only screaming at the gas pump occurred during the brief but troubling 1973-74 Arab oil embargo, when prices quadrupled from $2-$3 a barrel at the end of 1972 to $12 by the end of 1974.

With the new millennium, the benign indifference that we as a society had felt about oil began to morph into a vague curiosity and then into fascination. Suddenly, there seemed to be even more of a “Wild West” feeling in the business of oil than there had been in America’s wildcatting days after oil’s first discovery. We wanted to solve the riddle of how we had gotten into this mess and learn why every tyrant or upstart in every far-flung corner of the globe was holding our energy-dependent lifestyle hostage. We thought that if we could determine why the price of oil was climbing so quickly, then we might be able to find a way to reverse the trend and go back to “the good old days” when oil was just there and we didn’t have to think about it. This was the hope before the latest power shift brought a massive reallocation of global oil wealth and before a new and dangerous set of oil players had come into existence, creating new rules for geopolitics and setting us on a path toward chaos and violence. To understand how we got to this place, we need to look at where we’ve been.

Until the end of the nineteenth century, the main oil consumer was the United States, and the forces of supply and demand within the oil market maintained an equilibrium. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, powerful forces, mainly the Seven Sisters, which included U.S. and European oil companies, ruled the game. But, as new oil discoveries were made, power began to shift to the developing nations’ national oil companies (NOCs). The original members of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) were themselves NOCs, but they were largely under the thumb of the Saudis, who tried to maintain stability in the oil world, and, with a few notable exceptions, had not historically been one of the new national oil companies that were using their natural resources as weapons of aggression—the petroaggressors.

The Original Seven Sisters

1. Standard American Oil of New Jersey (later Exxon)

2. Royal Dutch Shell

3. British Anglo-Persian Oil Company (later British Petroleum)

4. Standard American Oil of New York (later Mobil)

5. Texaco America (later Texaco)

6. Standard American Oil of California (later Chevron)

7. Gulf Oil

Rise of the NOCs

In the beginning, it was largely the big oil companies that still controlled exploration and production, but the new oil states were eager to wrest control of their own oil industries from the hands of the major international oil companies and so began to see an opportunity for their independence.

The crucial turning point—the power shift—between the old oil world and the new oil order came in the early 1970s. The event was significant not so much in its financial impact as in its political impact. When the Saudis declared an oil embargo during the 1973-74 Yom Kippur War, it was the first time the world had faced oil shortages when oil was used as a political weapon.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a sleeping tiger and a sleeping elephant began to awaken. The economic engines of China and India, with their 1 billion-strong populations and desire to create their own middle classes, demanded oil to fuel their growth and fulfill their dreams of prosperity.

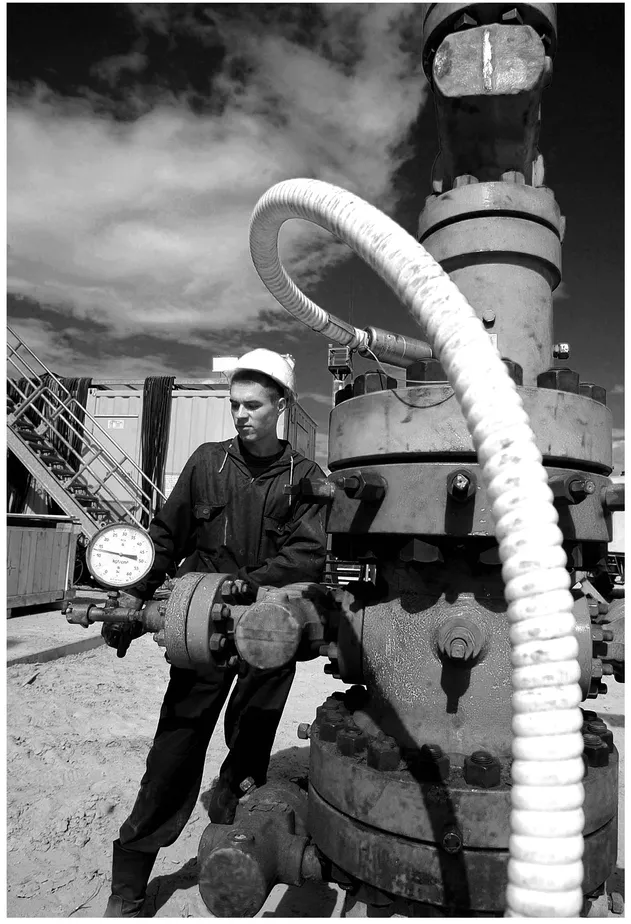

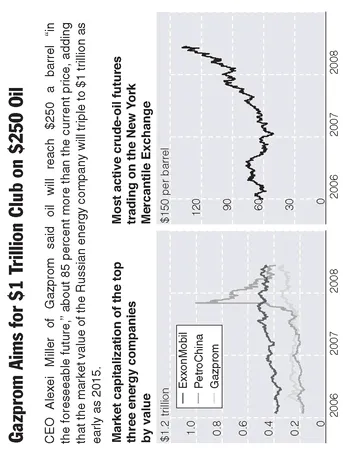

FIGURE 1-1 The diminishing supply of oil has led to a shifing cast of oil players—not only among the superpowers and the old “Big Oil” contenders, but also from the old players to the National Oil Companies (NOCs) in smaller, developing nations with highly unstable governments.

Source: Bloomberg.

It had been in the interest of the Saudis, the “alpha dogs” of OPEC, to keep the price sufficiently low so that consumers never felt pressure to seek alternative sources of energy. The Saudis sought to regulate oil prices by regulating the amount of oil they pumped. In the past, when prices had gotten too low, they pumped less; when prices became too high, they pumped more.

The system had worked fairly well. Westerners were loath to give up their oil addiction. Their established and luxurious lifestyles depended on it. But now there was a new dynamic as a result of the demand of the two emerging titans of Asia. India and China began to exert such a fierce pressure on oil supplies that the Saudis were finding it harder to keep oil prices low.

Third world rulers dreamed of finding oil the way they might have dreamed of winning the lottery: some to bring untold riches to their people, others simply to line their own pockets. The stage had been set for the next power shift—away from a stable and strong structure and toward the “anything goes” era of decentralization and the petroaggressors.

The rise of the NOCs, among them some of the most powerful oil enterprises in the world, was a key indicator that a new oil order now existed. Never even an issue before the early 1970s, the trend of higher oil prices seemed, by the early 2000s, to have taken on a frightening permanence. No feature of the new oil order had touched the immediate lives of so many people on a day-to-day basis as had rising oil prices.

The issue was not only about oil but also about what kind of oil, the most desirable being light sweet and the least desirable being heavy sour, with various other grades in between. The differences between grades related to the regions where they were produced and the technology and expense related to refining the different types and deriving useful distillate products.

THERE’S OIL, AND THEN THERE’S OIL

Crude oil comes in many varieties as categorized by sulfur content and viscosity. Oil that has a high sulfur content is referred to as “sour,” while oil that has a low sulfur content is “sweet.” Because sulfur is a pollutant, there are increasing “green” energy regulations that limit the use of distillates containing sulfur.

Viscosity relates to the density or thickness of the crude product (whether it’s liquid or tarlike). Tarry crude oil is considered “heavy,” and more liquid crude oil is “light.”

Different distillates can generally be derived from each type of oil, but heavy sour requires a more expensive refining process, and many refiners are not set up to refine heavy sour. That means that the oil supply-and-demand picture is not only about one commodity but also about supply and demand for specific products and available refining capacity. Gasoline, for example, has higher U.S. demand in the summer months. Heating oil has higher demand during winter.2

Light Distillates Light distillates include propane, butane, naphtha, and gasoline. Light sweet crude, which is both very viscous and low in sulfur, is the single most popular segment, for which there is growing demand. (Europe, for example, is gradually switching to more efficient diesel vehicles.) Unfortunately, light sweet crude comprises only about one-fifth of global output. Its leading producers are the United States, United Kingdom (North Sea Brent), Nigeria, Iraq, and western Africa.

Heavy Distillates Heavy distillates include heating oil and shipping fuel. The leading producers of heavy sour crude are Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran, Venezuela, Russia, and Mexico.

The New Petroaggressors

The changes that had begun in the oil world in the 1970s were subtle and often difficult to see at the time, but those changes were creating a power shift. Our exploration of the new oil order begins with two nations in Africa—Chad and São Tomé and Principe. For centuries, these had been resource-poor countries, but now in the twenty-first century, they were suddenly hoping to join the exclusive club of global oil producers. The irony and the potential for peaceful or violent rivalries were lost on no one.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Two African Oil Nations: A Study in Contrasts

By the 1990s, oil was becoming more and more difficult to find, and yet environmental issues prevented the harvesting of oil in areas where geological prospects were highly favorable. The large, oil-producing countries were no longer averse to turning oil into a political weapon—nor were the small ones. Disorder reigned. In retrospect, relative to the fierce competition and violence in the oil industry in the twenty-first century, the twentieth century looked almost benign. . . .

Suddenly, every drop of oil counted. Now, tiny and previously little-heard-from nations were finding their way into the global spotlight. What lay at the root of the power shift was oil: who had it, who needed it. An interesting contrast can be made in seeing just how the discovery of oil was handled in two African nations—São Tomé and Principe and Chad.

São Tomé and Principe

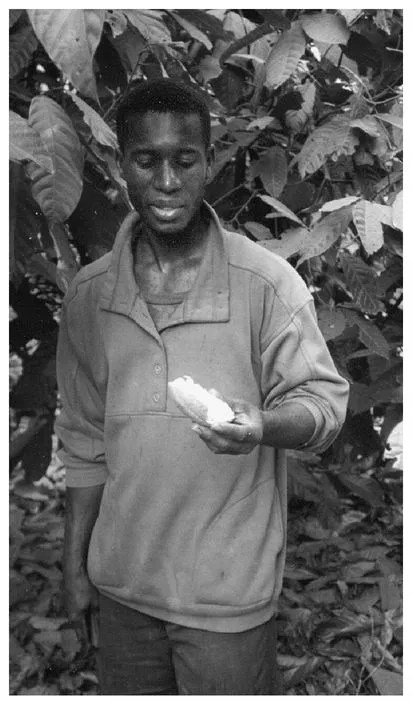

From May until October, it does not rain in São Tomé and Principe, the tiny, two-island nation 150 miles off the coast of western Africa. For decades, the local people had fished, picked fruit from the jungle, and manufactured cacao for export. São Tomé and Principe might have looked like a veritable island paradise, but, in reality, the islands’ citizens suffered in a yoke of poverty that they seemed unable to cast off. Even the high price of cacao had little impact on their fortunes; in the early 2000s, they had suffered from a recent drought, and they had badly mismanaged their agricultural system.

For the decade up until 2005, the national budget of São Tomé and Principe had been averaging about $50 million a year, much of it from traditional crops like cacao. Photo by Tom Cahill/Bloomberg News.

São Tomé and Principe was the second-smallest country in Africa. It had no significant natural resources, and almost half its population was under the age of fourteen. One of the poorest countries in the world, it was a sleepy nation that had so far largely escaped the world’s notice. In the past, the country had taken bailouts from Cuba, North Korea, and China just to survive. Like so many other tiny nations that were suddenly awakening to the modern world in the latter part of the twentieth century, São Tomé and Principe seemed to need a miracle.

In 2003, São Tomé and Principe’s per-capita gross domestic product was estimated at $1,200. Its annual budget showed only $74.11 million in revenues. It was that rarest of nation-states, peaceful within, and peaceful without. Political scientists like to say that resource-poor countries are far less likely than rich ones to plant democratic roots, and that they inevitably breed violence, but the citizens of São Tomé and Principe proved the academics wrong.

Democracy did grow in São Tomé and Principe, beginning in 1991, but violence did not. Two coups—one in 1995, the other in 2003—failed. Politics became a ferocious, fast-paced series of shifting coalitions. There were fourteen changes of government in a twelve-year period—more even than in most other African countries.

Because São Tomé and Principe possessed negligible reso...