![]()

Part One

Wired Markets

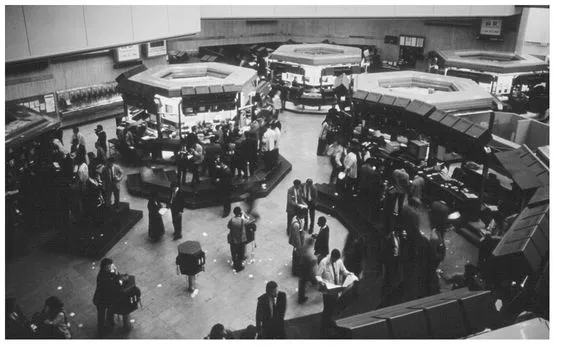

Not too long ago, going to a stock market meant you would meet lots of new people who were energetically shouting, running around, and making a mess with great quantities of paper. No more.Visiting a financial market now is more like visiting a telephone exchange. Computers and network gear hum in racks. Fans blow. Rows of tiny lights flicker. Occasionally someone shows up to replace a disk.

Technology did not suddenly transform our markets. It has been a gradual process, and understanding how we got here, and the simpler machines we used along the way, provides insight into today’s complex markets. In that spirit, the first chapter in this part, an illustrated history of market technology, gives an informative perspective on today’s wired markets.

Computers make a dramatic entrance into financial markets at the conclusion of Chapter 1. “So how did that work out?” you might ask.The second chapter answers that question, surveying some of the greatest technological hits influencing the markets.

Electronic markets are at the top of our greatest hits list. They are about the mechanics of trading, that is, the implementation of investment decisions (in contrast to actually making those decisions). Chapter 3, “Algorithm Wars,” is a more in-depth view of one of the most dynamic areas in electronic markets.

![]()

Chapter 1

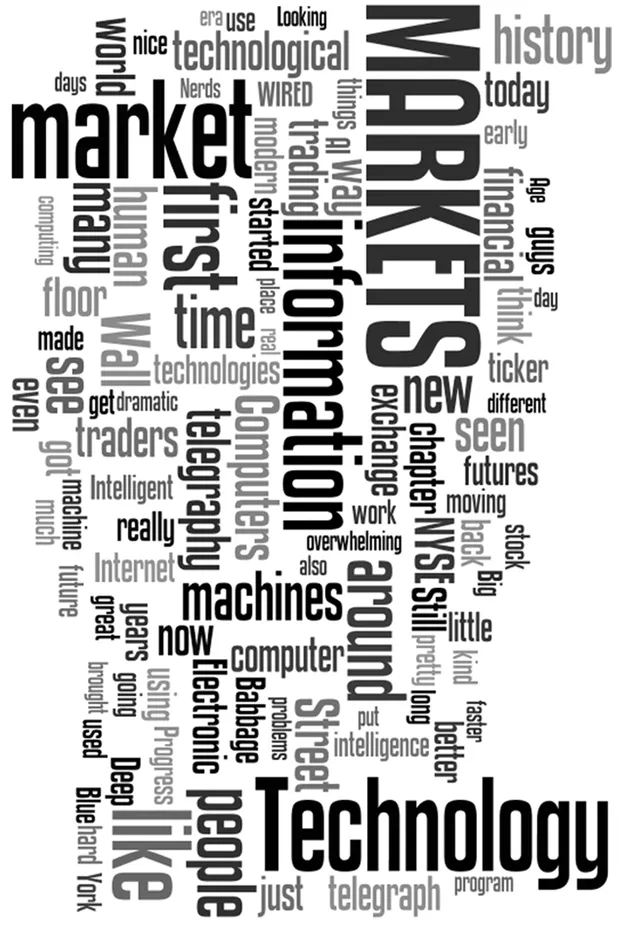

An Illustrated History of Wired Markets

Progress might have been all right once,

but it has gone on too long.

—OGDEN NASH

This chapter is based on a number of ever-evolving dinner and lunch talks I have given over many years, all called “Nerds on Wall Street” irrespective of their actual subject. Many financial conference speakers, including those talking to mixed professional/spousal audiences after open-bar events, are deadly dull; hardly anyone really wants to see yield curves over dessert and that last glass of wine. I started collecting photographs about markets and technology in the early 1990s, and tried to mix in some actual informative content. That, along with the natural sensibilities of a borscht belt comic, made me a popular alternative to the yield curve guys. Given the 20-minute rule for these talks, none of them were as voluminous as this chapter. Still, this is not intended in any way to be a complete history of market technology, but rather an easily digestible introduction. I occasionally still do these talks on what remains of greater Wall Street. I am also open to weddings, quinceañeras, and bar mitzvahs, since we all need diversified portfolios these days.

Looking into the workings of modern securities markets is like looking under the hood of a Prius hybrid car. There are so many complex and obscure parts it’s hard to discern what’s going on. If you look under the hood of an auto from a simpler era, for example a ’64 Mustang, you can see the parts and what they do, and have a better chance at understanding their complex modern replacements.

History repeats and informs in market technologies. From the days when front-running involved actual running to the “Victorian Internet era” brought on by telegraphy, we can learn a great deal from looking back at a simpler era.

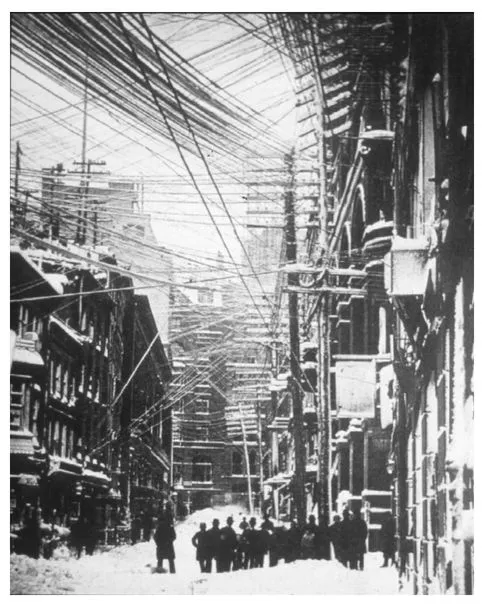

We think that the overwhelming influence of computers remaking the landscape around Wall Street today is something new, but a pair of before-and-after photographs show an even more dramatic technological invasion. Before telegraphy, in the 1850s, the sky over Wall Street was open and clear:

It took only a short time for telegraphy’s compression of time and space to transform the scenery. Here’s what the Street looked like shortly thereafter when everybody had to have it:

In its day, telegraphy was seen as the same kind of overwhelming transformation that the Internet is today. In many ways, the telegraph was more dramatic since it was the first time in human history that a message could be sent beyond the horizon instantaneously.

Technological transformations create problems. If we are lucky, more technology solves them.

Changes in markets brought about by technology are anything but subtle: The exchange floor in Tokyo closed down and was replaced by electronics in 1998. Here’s an earlier example, the London Stock Exchange trading floor the day before . . . ... and the day of the introduction of screen trading—the so-called Big Bang—on October 27, 1986.

You could have gone bowling and no one would have noticed.

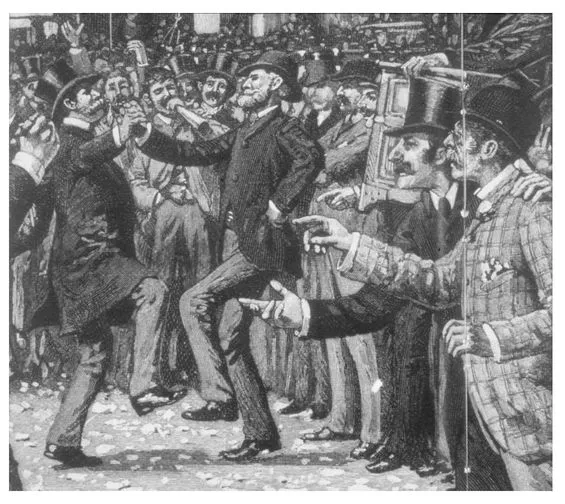

The trading floors that have been emblematic of financial markets around the world are an endangered species. Brokers and traders who used to rely on fast reflexes and agile elbows and knees now rely on computer programs, tweaked to be milliseconds faster than the next guy’s program.

Clearing the floor and rolling in the machines has a sentimental cost. When markets become technology, the human price of progress is high. Anyone who has been on the floor in New York or Chicago knows our markets are really personal, face-to-face, elbow-to-elbow, and knee-to-knee experiences. People are justifiably worried that when too much technology gets mixed up with markets, we’re going to lose some of the vibrancy that makes them so fascinating.

I have to admit, I’m a little sad when I hear about an exchange floor closing and being replaced by some screen trading system. Let’s face it. Having all those real traders in one place provides a sense of community and continuity.

A trading floor peopled with traders and brokers also makes for some colorful moments in market history, such as the opening of the live hog futures contract on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) in 1966. (These guys are definitely having more fun than loading the hog program on some Unix box in Amarillo—and on witnessing this, one wag asked, “Which ones are the brokers?”)

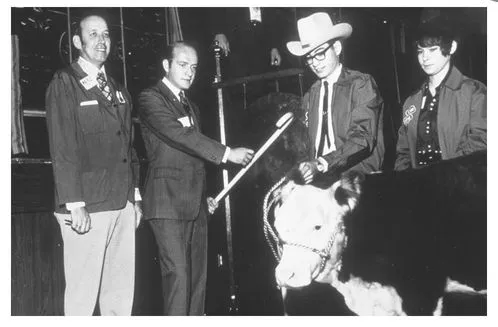

Or live cattle futures in 1964.

Or dead cattle futures in 1965.

Isn’t a dead cattle future sort of a contradiction in terms?

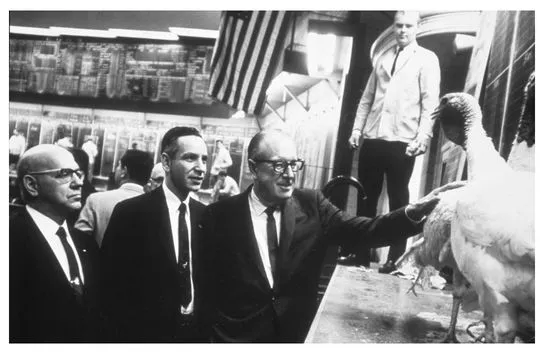

Or turkey futures in 1961.

Or Dutch guilder futures in 1973.

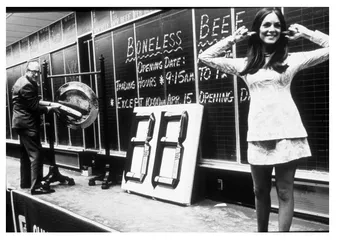

Or boneless beef futures in 1970, whatever that is.

Notice the same distinguished-looking CME official, Everett Harris, then president of the Merc, banging on the gong with a salami.This guy had a great job.These are the little details that make market history come alive for me.

There’s so much technology in modern markets that it’s easy to forget that some of our favorite markets, like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), started out as very low-tech places. In 1792, the New York Stock Exchange was a bunch of guys standing around a buttonwood tree at 68 Wall Street shouting at each other on days when it didn’t rain or snow:

We like our markets to be liquid, efficient, resilient, and robust. But this is hard to do when all the participants have to crowd around a tree and hope for good weather. So in 1794, we see the first big technological solution: the roof.

Everybody moves inside, to the Tontine Coffee House at the corner of Water and Wall streets.They’re still shouting, but they’re dry. Even when they’re warm and dry under a nice cozy roof, you can have only so many shouters participating in a market, and more participants is a good thing. Pretty soon technology solves this problem.

Hand signals and chalkboards worked really well. Now hundreds of people could participate in the market. Of course, this made for more broken trades. Here we see how they resolved them back in those days: the buyer dresses up in a bull suit, the seller dresses like a bear, and they duke it out up front.This was before all those beeping tape machines recorded everything everybody said.

When you’re indoors, you can also have dinners and parties to commemorate important events. Here we see two specialists celebrating the first bagging1 of a buy-side trader.

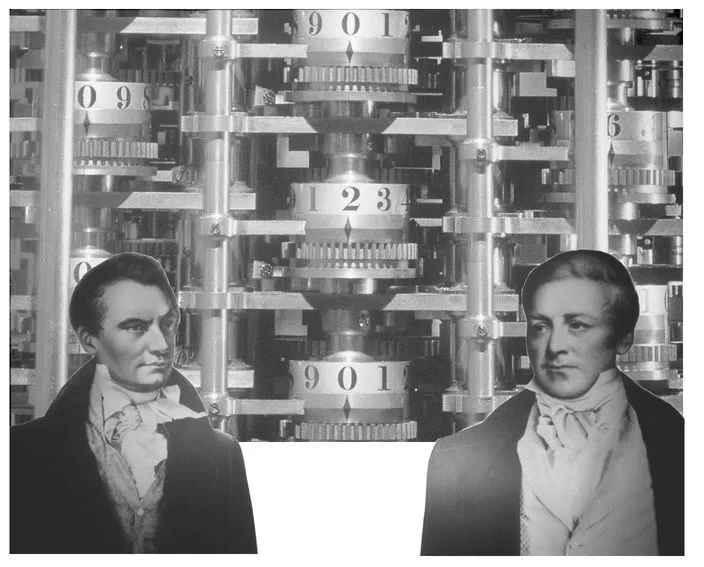

So far, the technologies we’re talking may sound rather low-tech: roofs, chalk, hands. Here’s what a computer looked like in 1823, the Difference Engine, invented by the famously brilliant, eccentric, and obnoxious Charles Babbage:

Here’s Babbage, who said, “I wish to God these calculations had been executed by steam.”

Here’s Babbage’s government sponsor, Prime Minister Robert Peel, who said, “What shall we do to get rid of Mr. Babbage and his calculating machine?”

Babbage was stunningly smart, and even more stunningly insufferable. He lost his government funding, and the idea of automatic computing languished for many years. It was not used in financial markets or anywhere else in the nineteenth century. Babbage only built pieces of his machine; but when the Royal Museum in London put a whole one together from his designs a few years ago, it worked perfectly. The world could have been a very different place if Babbage had better manners.We’ll pick up on him later.

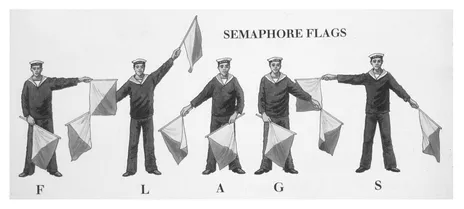

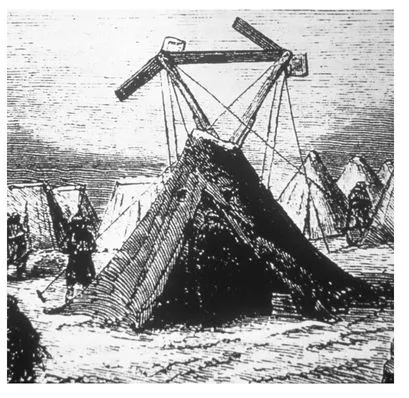

Now we have our happy traders signaling each other with their hands, dancing, and dressing up in bear suits. This is all very nice, but there’s a problem: the traders and brokers have to actually be present in person to participate in the market. How is this problem solved? With a little more technology, namely telegraphy. The earliest telegraphs weren’t the electric variety we think of at all. They were guys standing on hills waving flags, like the ones used at sea.

There wer...