eBook - ePub

CBT for Chronic Illness and Palliative Care

A Workbook and Toolkit

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

CBT for Chronic Illness and Palliative Care

A Workbook and Toolkit

About this book

There is a growing awareness of the need to address the psychological distress associated with physical ill health; however, current resources are limited and difficult to access. The best way to tackle the issue is by enhancing the skills of those professionals who have routine contact with them. CBT provides the evidence-based skills that most readily meet these requirements in a time and cost efficient manner. Based on materials prepared for a Cancer Network sponsored training programme and modified to address the needs of a larger client population of people experiencing psychological distress due to physical ill-health, this innovative workbook offers a basic introduction and guide to enable healthcare professionals to build an understanding of the relevance and application of CBT methods in everyday clinical practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access CBT for Chronic Illness and Palliative Care by Nigel Sage,Michelle Sowden,Elizabeth Chorlton,Andrea Edeleanu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie (CBT). We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Workbook: The Cognitive Behavioural Approach

Chapter 1

What is the Cognitive Behavioural Approach?

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) has been described by the pioneer of this therapy as:

An active, directive, time-limited, structured approach.

The therapy works by helping patients to:

Recognise patterns of distorted thinking and dysfunctional behaviour. Systematic discussion and carefully structured behavioural assignments are then used to help patients evaluate and modify both their distorted thoughts and their dysfunctional behaviours.

With the cognitive behavioural approach there is recognition of the way in which all our responses are part of a complicated interplay of actions and reactions. In physics we accept the general law that every action produces a reaction. What is not always so well appreciated is that this applies in psychology too.

We are generally aware that our actions have effects on those around us as theirs do on us. The simple act of smiling at someone when they look at you will produce a reaction in that person. Perhaps they will smile back, treating it as a simple greeting; alternatively, they may interpret it as an invitation to come over and chat; under other circumstances their reaction may be one of anxiety or hostility, if they think you are laughing at them. What ever it is your action will produce a reaction, and that reaction, in turn will have an effect on you. Even a “non-reaction” (such as no glimmer of acknowledgement that you smiled) will carry meaning and provoke a specific reaction in you.

So our social environment affects our behaviour and our behaviour affects our social environment. To a greater or lesser extent the same is true for our physical and economic environments. We can influence (if not control) our comfort, wellbeing, affluence and future prospects. Our comfort, wellbeing, affluence and future prospects similarly can and do influence how we think, feel and behave.

From the cognitive behavioural perspective, however, it is the loops of cause and effect within ourselves that are of special interest. When I put my hand too close to the fire, the outside world (external environment) of intense heat sends signals of pain to my body’s sensory receptors. From that point forward there are a series of reactions and interactions relating to my internal environment. The physical sensation of painful heat triggers emotional responses of intense dislike and thoughts of dangers to be avoided. But the most important and immediate reaction is a behavioural response of withdrawing my hand from the heat. Once this behaviour has happened, I experience a relief of the pain, my thoughts turn to labelling the hot object as something to be avoided or treated warily and it has acquired a negative emotional association.

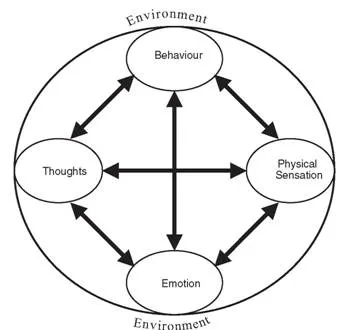

So, in this example physical sensation has evoked a specific behaviour, reappraising thoughts, and an unpleasant emotional reaction. But these four elements (physical sensation, behaviour, thoughts and emotions) can interact in different sequences.

Let us take another example:

Jenny plans a picnic and is looking forward to it; then, on the day, it rains. If this event leads her to think “my day is ruined”, then the emotional reaction will be as downcast as the weather, physically she is likely to experience a loss of energetic enthusiasm and her behaviour is likely to become restless and aimless. On the other hand, if the rain leads Jenny to think “ I’ll need a new plan for today”, then any emotional reaction of disappointment will be tempered by thoughts about what else she can do with the day; this will produce a physical response of increased energy for planning and a series of behavioural actions around sorting out an alternative arrangement.

The meaning Jenny attaches to the event (that is, the way she thinks about the rain) determines her emotional, behavioural and physical responses and ultimately, therefore, the outcome for her of this damp day.

When it is a one-off event of only minor consequence, like Jenny’s rainy day, then the effect of the way the event is interpreted is of no particular significance. However, when various events are lumped together in a single category and the same meaning is attached to all of the events in that category, then a pattern is emerging which is of greater influence in the person’s life. It can be very helpful to us at times to have categories to put things into and sets of beliefs or attitudes to which we regularly refer. But sometimes the categories and attitudes can prove problematic.

Once again an example may help illustrate the point:

John thinks he makes a fool of himself whenever he introduces himself to other people. Because of this his behaviour is to hang back and try to avoid having to do it. The emotion that this produces is one of acute anxiety and feelings of awkwardness or even fear. He therefore experiences physical sensations of nervous stomach, heart pounding, sweating and blushing.

To make matters worse these physical sensations make John think that everyone can see he is very anxious and will consider him to be making a fool of himself as he predicted. This makes his emotion of anxiety more intense so that when he does introduce himself his behaviour displays nervousness in his speech, inappropriate or incomplete remarks, a rather unfriendly manner and a very abrupt departure.

By introducing the behaviour of leaving the situation, John’s emotion is one of relief and this makes him think that he really is incapable of dealing with these social situations and should avoid them in future. This point of view is further supported by the physical sensations of exhaustion he feels afterwards which, to him, shows that he’s just not up to doing these things because they take too much out of him.

John has identified a category of events about which he has formed some firm beliefs which pre-determine his responses to future events that he associates with this category. He has acquired a pattern which will cause him problems in the future unless he can recognise it and find ways to change it.

The example of John illustrates the back and forth interplays between the internal elements and also the interaction between the internal world of the person and the external environment around him or her.

In Figure 1.1.1 there is a diagrammatic representation of these interactions. In Cognitive Behaviour Therapy we nickname this commonly used diagram the “Hot Cross Bun” and it was originally devised by Padesky and Mooney (1990). We will refer to it often during this book. It illustrates very clearly that despite its name, cognitive behaviour therapy does not focus on cognitions (or thoughts) and behaviour to the exclusion of feelings. However, for the examples above and in the Hot Cross Bun diagram the word “feelings” has not been used: a distinction is drawn between physical sensations and emotions. In daily life people do not always make these distinctions and will use the word “feelings” to describe both.

Figure 1.1.1 The Hot Cross Bun (adapted from Padesky and Mooney, 1990)

There are times when in cognitive behaviour therapy it is not important to separate the one from the other, but in work with people experiencing symptoms of physical ill health this distinction is often especially relevant; so explaining, understanding and emphasising this distinction can be very important.

Before leaving this introduction to the concepts of CBT, there are two more that cognitive behaviour therapists frequently use. One of these, like the “hot cross bun”, is another image: the “vicious circle” (originally referred to as the “exacerbation cycle” by Beck, 1976). This can be illustrated by returning to John for a moment: he had decided that he could not cope with introducing himself to new people; and this caused him to be anxious; in turn his anxiety caused him to fluff his lines; because he fluffed his lines he believed he was confirmed in his opinion that he could not cope with introducing himself to new people. In this way he completed a “vicious circle” back to his start point.

Self-fulfilling prophesies of this kind are an important feature of what maintains the “distorted thinking and dysfunctional behaviour” referred to by Hawton et al. above. Identifying and breaking these unhelpful circles is an extremely important feature of cognitive behavioural interventions that will be discussed further in this book.

Finally, a quick tour around the cognitive behavioural approach would not be complete without some reference to automatic thoughts. Beck (1976) identified these particular thoughts as an important component in recurrent emotional distress. So what are they?

First, recall the example of the hand near the fire. Once I’ve pulled my hand back from the hot object and decided it is hazardous to me, I do not repeatedly have these thoughts every time I encounter the hot object again. I behave in a way that avoids me hurting myself and I am emotionally wary of being too close to the fire. My reactions seem to be independent of further thinking. Clearly, if I was actually “thoughtless”, I would blunder into it and hurt myself; so I have seen it, recognised it as belonging to a certain category (of hot and harmful objects) and then responded according to that judgement. But this thinking process is very quick and I am hardly aware of doing it. We refer to these thoughts as “automatic”. They are the immediate interpretive and decision-making thoughts that are triggered when certain events occur in our environment. They are so fleeting and we are so little aware of them that we never think them through. This makes them very powerful and influential because we make decisions based on them and yet, because they are hardly noticed and remain unexamined, they are rarely changed by experience or new knowledge.

A realistic reappraisal of the “hot and harmful, therefore stand back” thought about the fire is unlikely to lead to a change in either my perception of the fire or the decision regarding appropriate behaviour. But John, on the other hand, in our last example, experiences recurrent emotional distress because of his automatic thought that he is “incapable of dealing with these social situations and should avoid them in future”. Like the perception of fire, this is also a self-protective strategy that alleviates immediate distress; but it leaves John at a major disadvantage in coping with a category of situations with which he will be faced time after time. Therefore, his episodes of distress will persist until he has had an opportunity to reappraise and change this thought process and the behaviour it directs him towards in favour of a strategy which he finds more effective in both alleviating immediate distress and managing the situations satisfactorily.

“Not coping” may often be considered to be the consequence of reducing emotional discomfort at the expense of satisfactorily dealing with situational demands or responding to demands at a high personal cost to emotional comfort. “Not coping” experiences are enough of a stimulus to begin an application of the cognitive behavioural model including identification of the automatic thoughts that are at work.

In the next chapter we will examine the relevance of this cognitive behavioural approach to people coping with life-changing physical health illnesses and disabilities, including those who expect their lives to be shortened by terminal illness. However, the cognitive behavioural approach is relevant to the experiences of all of us. We all have situations which we perceive as personal triumphs and disasters; we repeatedly fail to cope effectively with some challenges; we take for granted our abilities and skills that others lack. Sometimes people very close to us are puzzled as to why we are so unsure of ourselves in circumstances which they consider to be less difficult, and so confident when we face others they consider more difficult. We surprise ourselves at times by taking a strong dislike to something (or someone) for no logical reason.

Recognising the thinking patterns (cognitions), including the automatic thoughts, which underpin these personal behaviours and emotional reactions, can provide all of us with valuable insights into how we cope day-to-day. If that is good enough for our patients then it should be good enough for us. Learning and understanding the cognitive behavioural approach will be greatly enhanced by applying it to oneself. At the end of every chapter there will be exercises you are asked to complete before moving on through this training workbook. Please stick firmly to that way of working unless you are using this book as part of a training course which is covering the same points in different ways.

Whether you are using this book on a course or training yourself, these first exercises in applying the cognitive behavioural approach to oneself are an important place to start the learning process.

Exercises

Before you proceed to the next chapter ensure that you take the time to do the exercises included at the end of this chapter. To use this book properly you need to complete all the recommended exercises.

Exercise 1

1. Think about a good friend who you have not seen in a long time. Remember the good times you have had with this person and the things you like talking to them about.

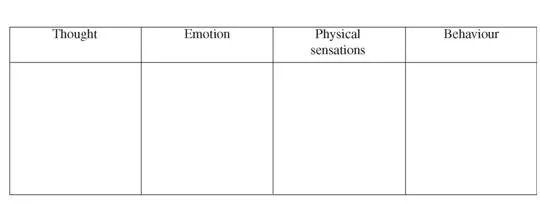

2. Now, imagine the phone rings; you pick it up; and there is your friend’s voice at the other end, calling for a friendly chat. What are your immediate thoughts on hearing their voice? What emotion do you feel? How does your body react? What behaviour do you adopt?

3. Write these things down in the boxes below.

You may find it easier to fill in some boxes than others. Emotions and physical sensations can be hard to tease apart. Sometimes we do not really notice the thoughts that go with the emotions. The behaviours might be quite small (like a smile or a frown). If you find that one box is still empty, then write in something that is probably the sort of thing that would be the right response. Remember that the responses in the other boxes give you clear clues as to what is likely to be right for this box. For example, if you think “oh dear, what’s wrong?” then the emotion is very likely to be worry or anxiety. If the emotion is annoyance then the thought may be something like “this is an inconvenient time to call” or some similar reason to trigger this emotional response.

Exercise 2

1. Imagine you are walking down the street in a local shopping area. It’s a pleasant day and you are in no particular hurry, looking in shop windows casually as you walk along.

2. Further on down the street walking towards you but some way off you see a friend who you enjoy talking to and bump into quite often when you are out like this. You smile in this person’s direction and feel quite sure that you have been spotted. Suddenly, this person disappears rapidly into the shop nearest to them without acknowledging you.

3. Imagine your reactions to this situation.

4. Now write them in the boxes below.

You may find you have quite a complicated set of reactions with more than one thought and emotion. Your behaviours may be a mixture too. In completing the boxes, try to ensure you have identified a specific thought for each emotion and vice versa.

Recommended further reading:

Greenberger D. and Padesky C. A. (1995) Mind Over Mood: A Cognitive Therapy Treatment Manual for Clients, New York: Guilford Press. A popular workbook for self-help from very influential cognitive behaviour therapists.

Padesky, C. A. and Mooney, K .A. (1990) Clinical tip: Presenting the cognitive model to clients. International Cognitive Therapy Newsletter, 6, 13–14 also available at www.padesky.com

Sanders, D. and Wills, F. (2005) Cognitive Therapy: An Introduction. London: Sage Publications.

Williams, C. (2003) Overcoming Anxiety: A Five Areas Approach, London: Hodder Headline Group. Along with Overcoming Depression in this same series, this is a British style of CBT selfhelp workbook and is backed up with a self-help website at www.livinglifetothefull.com

Chapter 2

The Relevance of a Cognitive Behavioural Approach for People with a Life-changing Illness

Receiving a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is not an event that will be received unemotionally by Janet, a 33-year-old happily married mother of two. Her reaction to this news is one of intense distress, as it is to her husband and parents. This is not abnormal; it is not the wrong way to react and there is no reason to suppose that because she reacts in this way that she is doing herself lasting harm. In fact, quite the opposite may be true: that to react quietly and calmly with no show of distress could be storing up an emotional dam-burst for later.

At the point of hearing bad news such as this, it is unlikely that CBT has a useful role to play for most people (whether the patient or a close family member). A cognitive behavioural approach may, however, have an important role in influencing the thoughts and behaviour of those of us who have to break that bad news or provide professional follow-up since our own thoughts of having “failed” or feeling “hopeless about the future” for this patient may affect our communication and the help we offer.

So, the cognitive behavioural approach is relevant to the way in which health care professionals manage their everyday work with people going through the sorts of adverse life experiences that nobody wants and most people dread.

But just because the distress experienced by patients and their families under these circumstances is “normal” and “understandable”, does not mean that there is no place for CBT. People vary greatly in their ability to accept, adapt and cope with the challenges of major health problems, especially life-threatening ones. The methods used in CBT focus on the practical here-and-now experiences in such a way as to be very relevant for those who are struggling to achieve these adjustments.

Early distress may be temporary, but for many people who are faced with life-changing ill health distress will be recurrent: life will become emotionally intense again at every point of change in health status or lifestyle. CBT techniques can be relevant in reducing the emotional intensity of these life events and encouraging a constructive response to new demands. For many people who are challenged in this way and for their families too, elements of CBT may be useful in assisting them to adjust to changed circumstances and also in becoming more resilient to further changes.

So a cognitive behavioural approach can help the healt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: The Workbook: The Cognitive Behavioural Approach

- Part II: The Issues: Some Psychological Problems

- Part III: The Toolkit: CBT Methods in Practice

- References

- Index