eBook - ePub

A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds

Beryl Rawson, Beryl Rawson

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds

Beryl Rawson, Beryl Rawson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds draws from both established and current scholarship to offer a broad overview of the field, engage in contemporary debates, and pose stimulating questions about future development in the study of families.

- Provides up-to-date research on family structure from archaeology, art, social, cultural, and economic history

- Includes contributions from established and rising international scholars

- Features illustrations of families, children, slaves, and ritual life, along with maps and diagrams of sites and dwellings

- Honorable Mention for 2011 Single Volume Reference/Humanities & Social Sciences PROSE award granted by the Association of American Publishers

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds by Beryl Rawson, Beryl Rawson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Ancient & Classical Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Houses and Households

CHAPTER 1

Family and Household, Ancient

History and Archeology: A Case

Study from Roman Egypt

History and Archeology: A Case

Study from Roman Egypt

1 Introduction

The domestic sphere in Greek and Roman antiquity has arguably been the focus for some of the most exciting and innovative recent research in the fields of both ancient history and classical archeology. (While not all of their practitioners would agree, for the purposes of this chapter I am defining “ancient history” and “classical archeology” broadly, with ancient history encompassing epigraphy and papyrology as well as literary-based studies, and classical archeology including methodologies inspired by anthropological archeology in addition to the more traditional forms of art historical and architectural analyses.) This shared interest in the domestic realm would seem to make it ideal territory for collaboration, or at least dialog, between ancient historians and classical archeologists. So far, however, such dialog has been relatively limited, with the two groups of scholars tending to address rather different kinds of questions. With respect to Classical Greece, for example, historians have focused on Athens and have tended to be concerned with topics such as the legal status of individual family members and affective relationships between them. Archeologists, on the other hand, have often looked more broadly across the Greek world and addressed questions such as the degree of cultural variation between cities and the nature of the domestic economy (see Trümper, this volume). Where topics have been addressed from both sides of the divide, as, for instance, with the question of the extent of female seclusion in Classical Athens, the arguments put forward on the basis of the archeological evidence have been slow to be addressed by those working with other types of material. (In fact, even scholars working on this one issue using different types of archeological evidence have not always taken account of each others’ conclusions (see Bundrick (2008) 309–10).

Among a variety of factors likely to have contributed to this state of affairs, I would like to single out for discussion here one in particular, which is that the evidence used by historians tends to inform us about slightly different aspects of domestic life from that used by archeologists. For, while historical sources most frequently offer insights into the “family,” archeological material almost invariably relates to the “household.” This distinction is more important than it may appear. In modern, Western society the terms “family” and “household” often refer to the same entity, namely, a group of people living together under the same roof. In the context of the ancient world, too, there is some degree of overlap, and therefore ambiguity, in the terminology relating to families and households. In Greek and Latin the household is elided linguistically, and arguably also conceptually, with both the family and also with the physical structure of the house (familia and domus in Latin, oikos in Greek). Nevertheless, as anthropologists have long realized, “family” and “household” actually have precise and distinct meanings which are analytically important: households by definition do not necessarily comprise people related by blood, while those who are closely related biologically may reside in different houses. Thus, when an archeologist looks at a house, she cannot “see” the possible biological or social relationships between its occupants, while a historian reconstructing a family’s genealogy cannot “know” where individual family members resided at any particular point in time unless this is explicitly stated in his source material. Where relevant information does exist, some text-based studies have managed to cross this divide successfully (for example, Bradley (1994) 76–102 on household slaves; Cooper (2007a) on the character of households in Late Antiquity). But the nature of the evidence has meant that it is virtually impossible for archeology to do the same. These problems have led archeologists and historians to ask different kinds of questions, playing to the strengths of their sources, but such a strategy makes it hard to reach conclusions which add up to more than the sum of their collective parts.

In this chapter I explore the problem and suggest some possible ways in which ancient historical and archeological research might fruitfully be brought into closer dialog in the investigation of the domestic sphere. I use as an example evidence from villages in Roman Egypt. Because the arid conditions here have led to the exceptional preservation of organic material, the region combines some of the most extensive and detailed textual information on families (which survives in the form of documentary papyri) with some of the best-preserved domestic architecture anywhere in the classical world. While this information is atypical in its level of detail, it makes a good test case since it is surely here, if anywhere, that the possibility exists of bringing archeology and text closer together and of drawing methodological conclusions which can be useful in other parts of the ancient world. Not by coincidence, scholars working with this material have already begun to use the two sources in tandem, and it is with some of these studies that I begin my discussion.

2 Archeology and Text in the Investigation

of Households and Families in Roman Egypt

of Households and Families in Roman Egypt

While the archeological sites of Roman Egypt represent an outstanding opportunity in terms of the range of materials surviving, the long history of investigation at many of them has meant that the interests of investigators, and therefore the kinds of study they have undertaken and the information they have chosen to record, have changed through time. I want to focus here on two sites which illustrate both the potential and the difficulties involved in trying to work with the full range of evidence from these sites in the most productive way. These are the villages of Karanis in the Fayum, inhabited from the second century BCE until at least the late fourth century CE, and Kellis in the Dakhleh Oasis, which was occupied from the first century BCE to the fourth century CE.

Karanis was first explored by archeologist Flinders Petrie in the late nineteenth century and a few years later by the papyrologists Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt. The primary aim of most of this work was to recover papyri, and little account was taken of the archeological context from which those papyri were retrieved. In 1925 fresh excavations were initiated by the University of Michigan. By this time large sections of the village, including its center, had disappeared, carried away for use as fertilizer because of the high organic content. Nevertheless, enough remained for the Michigan team to initiate a project aimed both at recovering papyri and also at learning something about the life of the village from the exceptionally well-preserved houses in which most of those papyri were found. Although there was considerable variation, many of the houses were relatively small (ca. 30m2 in ground area). The ground floor most frequently comprised two rooms with additional living space in one or two upper storeys, and storage in a subterranean basement. Most of these dwellings also had the use of an external courtyard which played a major role in the lives of the occupants, serving as the location for animal pens, ovens, and a variety of other facilities (Figure 1.1).

Between 1925 and 1935 an immense volume of material was recovered from Karanis. Study of the papyri has still to be completed (see Gagos (2001) 517–18), while the architecture has been published only in summary form (Husselman (1979) xi). Scholars have long been aware of the potential of the papyri to provide insights into family life (for example, Bell (1952)), but in the publications the approach to the architecture and the many artifacts recovered from the site was purely descriptive (as was the case with the archeological remains of housing throughout the classical world until recently). Lately, initiatives by papyrologists working with the Karanis material have raised the possibility of reuniting papyrological and archeological evidence in order to explore domestic social life from both perspectives together. These have been encouraged by an increasing tendency to study documents as groups or archives, rather than in isolation (Gagos (2001) 514–16), as well as by a desire to adopt a more problem-oriented approach to the texts themselves (tentatively labeled the “New Papyrology” by Bruce Frier (1989) 217–26).

Figure 1.1 Courtyard of house C118, Karanis, viewed from the southeast. Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. Karanis Excavations of the University of Michigan in Egypt, 1928–1935: topography and architecture, Kelsey Museum Studies Vol. 5. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, plate 87b.

Image not available in this digital edition.

In 1994 Peter van Minnen proposed a “house-by-house or family-by-family” approach to Karanis and its material remains (van Minnen (1994)). Van Minnen used as an example a house (dubbed B17 by the excavators) which yielded a particularly rich group of Greek papyri, many of them relating to a man named Socrates. Based on this collection of private letters, tax receipts and other documents, together with related material found elsewhere at Karanis, van Minnen was able to discuss Socrates’ occupation (tax-collector), sketch his character (a man of learning but with a sense of humor), outline his family tree (including naming his parents, brother, wife, and children) and suggest the approximate year of his death (shortly after 171 CE). The texts thus provide a rich vein of information about Socrates and his family. As van Minnen pointed out, however, there are some topics which they do not address. It is here, he argued, that archeology should play a role. Based on the estimated size of the house, van Minnen suggested that at least seven people may have resided there, but he was unable to determine who these individuals may have been. He proposed that items such as castanets and spindle whorls, listed among the objects found in some of the rooms, were evidence of the presence of women, although the identities of those women could not be known.

No plan of house B17 appears to have been recorded by the excavators. It is therefore impossible to place in an architectural context the castanets and other items listed as being found here, in order to explore what the organization of activities might reveal about the identities of the different members of household. Equally importantly, a lack of stratigraphic information for this building means that it is difficult to tell when most of the items were deposited. Van Minnen’s interpretation assumes a rather static picture of the architecture and its occupants. But while it might be tempting to identify Socrates’ inkwell among the objects recovered from “his” house, we need to recognize that the material from that house represents a palimpsest, a partial record of a sequence of activities carried out by a number of individuals over many years or perhaps even over several generations. Given these problems there is a limit to where the archeology of house B17 can take us in the search for information about Socrates and his family.

Van Minnen, however, has not been the only scholar to argue for a more interdisciplinary approach to understanding the domestic sphere at Karanis. Robert Stephan and Arthur Verhoogt have recently begun to restudy a different documentary archive, this time belonging to the soldier Claudius Tiberianus, written in both Greek and Latin and coming from house B/C167, which is rather better documented in the excavation records (Stephan and Verhoogt (2005)). Stephan and Verhoogt’s interest arose from their discovery that this relatively well-known group of letters belonged to a larger collection of documents all found in the same house, many in a single archeological context. The additional material is enabling them to investigate Tiberianus’ family in more depth than has been done previously, revealing the identities of further individuals who may have been related to him. At the same time, they have also been prompted to consider what else might be learned about his household using archeological evidence from the house, and this study is still ongoing. Stephan and Verhoogt are rightly cautious about the association between their archive and the house in which it was found. As they point out, it is impossible to know with any certainty who lived here and how the majority of the letters came to be stowed under the stairs where the excavators found them. At the same time, although a plan of the house is available, it is unclear how the objects found relate to the two successive architectural phases of the building, which seems to have been in use for about a century.

Some of the difficulties encountered both by Stephan and Verhoogt and by van Minnen result from problems with the excavation and record-keeping of the individual buildings they have been looking at. But there is also a variety of other factors which complicate interpretation of the site. In addition to disturbance by previous investigators and fertilizer-diggers there is also uncertainty about the date at which the settlement was finally abandoned (Pollard (1998)). Unless they can be resolved, such questions will hamper attempts to reinterpret any house (or other building) at Karanis.

In some ways the outcome of these two studies is discouraging: in such rare cases where it seems that archeology and texts should be able to “speak” directly to each other, their juxtaposition does not seem to have offered much more information about the families or households in question than could have been gleaned from the texts alone. In the case of house B/C167 it is unclear whether Tiberianus ever even lived in the house, or whether the archive of letters was kept and passed on by others inside or outside the family, until it was finally forgotten under the stairs. Thus, it is hard to know what relevance the architecture and finds may have for any investigation of his household. Even if we accept van Minnen’s assumption that house B17 was inhabited by Socrates, neither the archeology nor the texts can tell us who else lived there with him. In both instances, then, the documents reveal interesting detail about the individuals and families in question, but the archeology fails to match this level of resolution. Furthermore, even when both sources are combined it is not possible to be precise about the nature of the social group living in any one specific structure. How far is this a problem with the nature of the evidence from Karanis in particular, and how far is it a more general difficulty with trying to use texts and archeology together in this way?

To explore whether data from a different site which lacks some of these shortcomings will give more productive results, I want to turn to some of the possibilities offered by material from the village of Kellis in the Dakhleh Oasis, some 200 miles west of the Nile valley, where recent work has also attempted to bring texts and archeology together to reconstruct households. Here again, exceptional preservation of domestic architecture is coupled with a rich array of texts, mainly in Greek and Coptic. Included are private letters as well as official documents relating to the lease and sale of property, loan agreements, receipts and other financial records. Work at the site is still continuing, which means that a final archeological publication is not yet available, but preliminary reports provide sufficient material to explore how far juxtaposing the archeological and written sources can enhance our understanding of the erstwhile inhabitants.

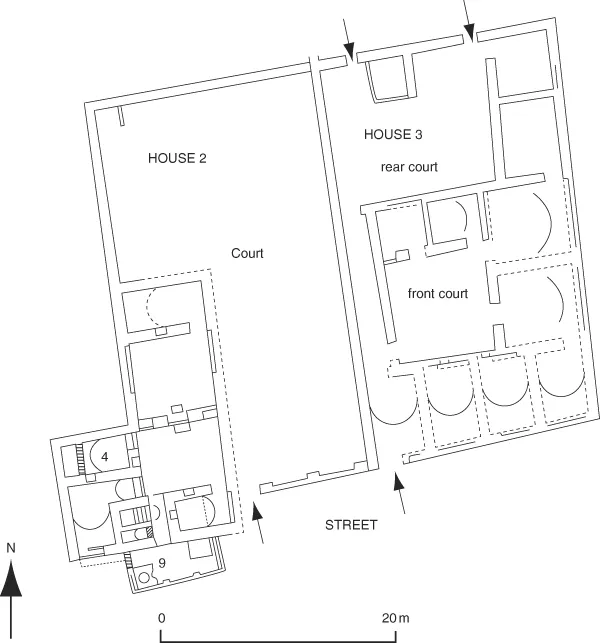

The houses at Kellis are somewhat different from those at Karanis: instead of being on multiple levels they generally seem to have been single storey, with a larger number of rooms, which were organized around one or two internal courtyards. I focus here on two adjoining properties, houses 2 and 3 in Area A, at the center of the site, which were constructed early in the fourth century CE and abandoned close to the end of that century. These are not among the most elegant found so far (larger residences of somewhat earlier date with wall-paintings and central spaces resembling atria were located elsewhere, in Area B: Hope and Whitehouse (2006)), but they do offer a relatively close parallel for the Karanis structures in terms of the quantity and range of documents recovered.

On the basis of an archive found inside, house 2 has been interpreted as the home and workplace of a carpenter named Tithoes son of Petesis, who lived during the second half of the fourth century CE and whose family tree can be partially reconstructed over three generations. But the situation is complicated: a further group of texts from the same house relates to a second individual, Pausanias son of Valerius, who, the excavators suggest, may also have occupied the house but perhaps at an earlier date, during the mid-fourth century CE (Hope (1997) 9).

By looking further at the archeological evidence for the organization of the house itself, the Kellis team have been able to add an extra dimension to their discussion: house 2 is modest in size and irregular in plan (Figure 1.2). An L-shaped residential section, entered from the south, comprised eight rooms. The occupants may also have had access to a large courtyard to the east. A further, unroofed, space (room 9) was added by annexing part of the street on the south side and seems to have been used for cooking. Among the finds from this area were two wooden codices. Elsewhere in the house (room 4) were found carpentry tools together with sections of wood which may have been in the process of being prepared for the manufacture of further codex pages (Hope (1997) 9).

Figure 1.2 Plan of houses 2 and 3, Kellis; plan redrawn based on Hope (1987) fig. 2.

It is, of course, tempting to connect the documents referring to Tithoes the carpenter with the woodencodices and carpentry tools found here. Colin Hope, the excavator, is rightly cautious, however, stressing that one cannot assume that either the tools or the wooden codices were necessarily associated with Tithoes, since it cannot be p...