![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Asset Allocation

For most investors, asset allocation and its meaning seems relatively straightforward, that is, the process of allocating assets. It is the how and the why of asset allocation that has led to an entire asset management industry dedicated to its operation. Given the amount of resources and effort dedicated to understanding asset allocation, it would be reasonable to expect that after almost 5,000 years of human history there would be a suitable solution. The fact that the investment management industry is still groping for an answer is illustrated in the millions of references to “asset allocation” from any Internet search and the fact that there are enough practitioner books and academic articles on “how to allocate assets” to fill any investor’s library. This chapter provides a brief history of how major advances in financial theory and investment practice affected investors’ approach to asset allocation and how asset allocation has had to evolve to meet changes in economic, regulatory, and technological environments. However, given the range of current and past efforts to diagnose, describe, and prescribe the process of asset allocation, it seems relatively futile to provide any reasonable summary of how we got here, much less what “here” is.

Before reviewing how we have arrived at current approaches to asset allocation, a brief review of what asset allocation is seems appropriate. Simply put, the ability to estimate what the future returns and risks of a range of investors’ acceptable investments are and to choose a course of action based upon those alternatives is at the heart of asset allocation. As a result, much of asset allocation is centered on the quantitative tools or approaches used to estimate the probabilities of what may happen (risk) and the alternative approaches to managing that risk (risk management). While the concept of risk is multi-dimensional—including various types of market risks as well as liquidity risk, operational risk, legal risk, counterparty risk, and so on—for many it is simply the probability of a bad outcome. There is simply no single approach to asset allocation that covers all individuals’ sense of risk tolerance or even what risk is. In the world of asset allocation, we generally concentrate on the concept of statistically driven risk management since those risk measurements are often centered on statistical estimates of probability (which is measurable) rather than on the concept of uncertainty (or possibility management), on which our empirically driven asset allocation models have little to say.

As a consequence, there is risk or uncertainty even in the most basic concept of asset allocation. Much of what we do in asset allocation is based on the tradeoffs between the risks and returns of various investable assets as well as the risks and returns of various aspects of asset allocation, including alternative approaches to return and risk estimation. Choosing among the various courses of action lies at the heart of a wide range of asset allocation approaches, including:

• Strategic asset management (allocation across various investment classes with the goal of achieving a desired long-term risk exposure)

• Tactical asset management (allocation within or across investment classes with the goal of maximizing the portfolio ’s short-term returnrisk profile)

• Dynamic asset management (systematic changes in allocation across assets with the goal of fundamentally changing the portfolio’s risk exposure in a predetermined way)

Asset allocation is not about solely maximizing expected return. It is a central thesis of this book as well as years of academic theory and investment practice that expected return is a function of the risks taken and that those risks may not be able to be measured or managed solely through systematic algorithmic based risk management. Thus, asset allocation must focus on risk management in a broader context, including the benefit of an individual asset allocators’s discretionary oversight in order to provide a suitable return to risk tradeoff consistent with an investor’s risk tolerance or investment goals. The story of the evolution of our understanding of that return to risk tradeoff is the subject of this chapter. It is important to emphasize the “evolution” part as our understanding of the expected return to risk relationship keeps changing. First, because through time we learn more about how individuals react to risk and second, because the world itself changes (the financial world included).1

An individual’s or institution’s approach to asset allocation depends of course in part on their relative understanding of the alternative approaches and the underlying risks and returns of each. For the most part, this book does not attempt to depict the results of the most current research on various approaches to asset allocation. In many cases, that research has not undergone a full review or critical analysis and is often based solely on algorithmic based model building. Also, many individuals are simply not aware of or at ease with this current research since their investment background is often rooted in traditional investment books in which much of this “current research” is not included.2

IN THE BEGINNING

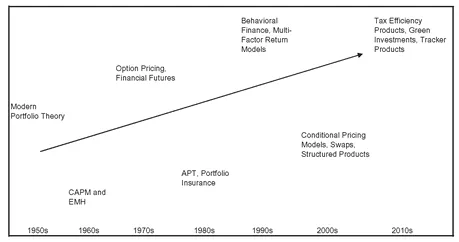

It should be of no surprise to investors that the two fundamental directives of asset allocation: (1) estimate what may happen and (2) choose a course of action based on those estimates have been at the core of practitioner and academic debate. For our purposes, the timeline of that debate is illustrated in Exhibit 1.1. The advent of Modern Portfolio Theory and practice is often linked to the publication of Harry Markowitz’s 1952 article “Portfolio Selection.” For many the very words “Modern Portfolio Theory” are synonymous with Markowitz. It is important to point out that Modern Portfolio Theory is now almost 60 years old. As such, and not merely as a result of age, MPT (Modern Portfolio Theory) is really IPT (Initial Portfolio Theory) or OPT (Old Portfolio Theory). Moreover, the fundamental concept expressed in Markowitz’s article (the ability to manage risk based on the expected correlation relationships between assets) was well known by practitioners at the time of its publication.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Timeline of Financial Advances in Asset Allocation

Markowitz formalized the return and risk relationship between securities in what is known today as the mathematics of diversification. If expected single-period returns and standard deviations of available securities as well as the correlations among them are estimated, then the standard deviation and the expected return of any portfolio consisting of those securities can be calculated. This means that portfolios can be constructed with desirable standard deviation and expected return profiles. One particular set of such portfolios is the so-called mean-variance efficient portfolios, which have the highest expected rate of return for a given level of risk (variance). The collection of such portfolios for various levels of variance leads to the mean - variance efficient frontier.3 In the mid 1950s, James Tobin (1958) expanded on Markowitz’s work by adding a risk-free asset to the analysis.4 This brought into focus an individual ’s ability to hold only two types of assets (risky and riskless) and to lend or borrow such that those two assets provided the tools necessary to match a wide range of investor return and risk preferences.5

The next major advancement in asset allocation expanded the work of Markowitz and Tobin into a general equilibrium model of risk and return. In this work, academics treated volatility and expected return as proxies for risk and reward. In the early 1960s, academics (Sharpe, 1964) proposed a theoretical relationship between expected return and risk based on a set of assumptions of individual behavior and market conditions. These author(s) proposed that if investors invested in the mean -variance efficient market portfolio, then the required rate of return of an individual security would be directly related to its marginal contribution to the volatility of that mean-variance efficient market portfolio; that is, the risk of a security (and therefore its expected return) could not be determined while ignoring its role in a diversified portfolio.

A REVIEW OF THE CAPITAL ASSET PRICING MODEL

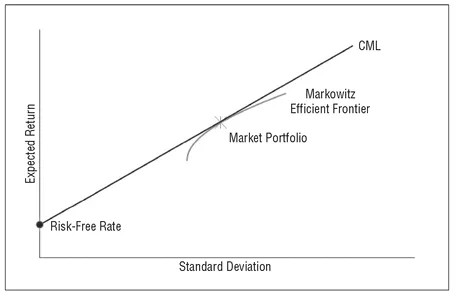

The model developed by Sharpe and others is known as the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). While the results of this model are based on several unrealistic assumptions, it has dominated the world of finance and asset allocation for the past 40 years. The main foundation of the CAPM is that regardless of their risk-return preference, all investors can create desirable mean-variance efficient portfolios by combining two portfolios/assets: One is a unique, highly diversified, mean-variance efficient portfolio (market portfolio) and the other is the riskless asset. By combining these two investments, investors should be able to create mean-variance efficient portfolios that match their risk preferences. The combination of the riskless asset and the market portfolio (the Capital Market Line [CML] as shown in Exhibit 1.2) provides a solution to the asset allocation problem in a very simple and intuitive manner: Just combine the market portfolio with riskless asset and you will create a portfolio that has optimal risk -return properties.

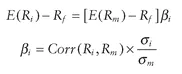

In such a world, the risk of an individual security is then measured by its marginal contribution to the volatility (risk) of the market portfolio. This leads to the so -called CAPM:

where

Rf = Return on the riskless asset

E(Rm) and E(Ri) = Expected returns on the market portfolio and

a security

σm and σ i = Standard deviations of the market portfolio

and the security

Corr(Ri, Rm) = Correlation between the market portfolio and

the security

EXHIBIT 1.2 Capital Market Line

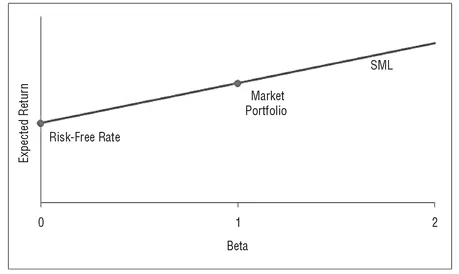

EXHIBIT 1.3 Security Market Line

Thus, in the world of the CAPM all the assets are theoretically located on the same straight line that passes through the point representing the market portfolio with beta equal to 1. That line is called the Security Market Line (SML), as shown in Exhibit 1.3. The basic difference between the CML and the SML is one of reference system. In the CML the risk measured is total risk (standard deviation), while the risk measured in the SML is a security’s marginal risk to the market portfolio (beta).

While the most basic messages of MPT and CAPM (that diversification is important and that risk has to be measured in the context of an asset ’s marginal contribution to the risk of reference market portfolio) are valid and accepted widely by both academics and practitioners, many of their specific recommendations and predictions are not yet fully accepted and in some cases have been rejected by empirical evidence.6 For instance, observed security returns are very weakly, if at all, related to a security ’s beta, and most investors find a simple combination of the market portfolio and the riskless asset totally inadequate in meeting their risk-return requirements.

ASSET PRICING IN CASH AND DERIVATIVE MARKETS

CAPM and EMH

As discussed in greater detail later in this book, the CAPM profoundly shaped how asset allocation within and across asset classes was first conducted. Individual assets could be priced using a limited set of parameters. Securities could be grouped by their common market sensitivity into different risk classes and evaluated accordingly; and, to the degree that an expected market risk premia could be modeled, it would also be possible (if desired) to adjust the underlying risk or beta of a portfolio to take advantage of changes in expected market risk premia (i.e., increase the beta of the portfolio if expected market risk premia is high and reduce the beta of the portfolio if the expected market risk premia is low). Here, market risk premia is defined as the difference between the expected rate of return of the market portfolio and the “riskless rate of interest.”

While the CAPM is at its heart a model of expected return determination, it quickly became the basis for a number of asset allocation based decision models. The rudimentary nature of computers in the early 1960s is often forgotten and, while the mathematics of the Markowitz portfolio optimization model were well known, the practical application was limited due primarily to the number of numerical calculations. Specifically, the amount of data needed to obtain reasonable estimates of the covariance matrix is significant. For instance, if we have 100 securities, then to estimate the covariance matrix, we would need to estimate 100 variances and (1002 - 100)/2 covariances, which add up to 5,050 parameters, have to be estimated. This would be computationally difficult and would have required many hours of work. As an alternative, the number of calculations can be significantly reduced if it is assumed that returns are driven by only one factor (e.g., the market portfolio). Note that this does not assume that CAPM holds. In other words, suppose we use a simple linear regression to estimate the beta of an asset with respect to a well diversified portfolio.

The rate of return on the asset at time t is given by Rit, the rate of return on the diversified portfolio is given by Rmt, the intercept and the slope (beta) are given by α i and β i respectively. Finally, the error term for asset i is given by eit. Suppose we run the same regression for another asset, denoted asset j. If the error term for asset j is uncorrelated with the error term for asset i, then the covariance between the two assets is given by

Cov (Ri , Rj ) = βi β jVar (Rm )

Notice that to estimate covariance between the two assets, we need an estimate of the variance of the market portfolio as well (Var(Rm)). However, this term will be common to all estimates of covariance. The result is that the number calculations required to estimate covariance matrix is now reduced to (2 × 100 + 1).

It is important to note that the above regression model, known as the market model, has nothing to do with the CAPM. The above regression makes no prediction about the size or the sign of intercept. It simply a statistical relationship used to estimate the beta. On the other hand, the CAPM predicts that the market model intercept will be (1 - βi)Rf.

It is fair to say, however, that almost 40 years ago most academics and professionals knew that the CAPM was an “incomplete” model of expected return. We now know that Sharpe and his fellow academics had unwittingly created a sort of “Asset Pricing Vampire,” which rose from their model and, despite 30 years of stakes driven into its heart lives to this day for many practitioners as the primary approach to return estimation.7 In the early years of the CAPM, financial economists were like kids with a new hammer in which everything in the financial world looked like a nail. For example, if an asset’s expected return can be estimated, then that estimate could be used as a basis for det...