![]()

1 Projects, Project Management, and Program Management

Projects are a kind of work that is temporary, unique, and progressively elaborated. Accordingly, project management is a discipline that includes a specific body of knowledge as well as a specialized set of tools. In this chapter, we explain how project management is different from process management and ad hoc management, the nine knowledge areas—stressing the importance of integration and managing expectations— and overview five managerial functions.

Project success doesn’t just “happen”; it comes from people using commonsense tools that are suited for the special nature of projects and applied in an organizational environment that accepts discipline and rigor. To understand what makes project management “successful,” we need to start with its basic unit, which is the project. In this chapter, we will explain what a project is and isn’t and describe the foundations of project management as a discipline.

PROJECTS ARE A TYPE OF WORK

It is important to understand what a project is so that the project manager and project team can select appropriate project management tools. This section provides a basic definition of a project.

First, let’s examine some characteristics of any kind of work activity, including projects. Thus, all work, including projects:

- Uses resources. For the purpose of this definition, resources include people, capital, equipment, ideas, and so forth. Whether the organization is refining oil, building a building, programming a computer, conducting a management consulting assignment, designing an instrument for a satellite, developing a new product or service, or surgically removing a cancerous tumor, a manager is responsible for the effective application of resources.

- Is requested or needed. Customers, and their willingness to spend their scarce money for goods and services, are the lifeblood of any organization, be it government, business, or charity. Successful organizations pay attention to customer needs to deliver goods and services that customers’ value.

- Has goals. Generically, management is a process of establishing goals and directing resources to meet those goals.

These three factors are descriptive of projects but are not sufficient to distinguish a project from a nonproject. The accepted definition of a project is that it is a temporary work effort that produces a unique result. Let’s look at each of the three characteristics that distinguish projects from other kinds of work:

- Projects are temporary. Temporary means that there is a beginning and end to the project. Projects start when the sponsoring organization authorizes the project, and projects end when the project meets the requirements. All well-managed projects must come to an end! For example, the project of constructing a major downtown hotel would take one or two years to complete, but the project would complete the work.

- Projects are unique. Unique means that the work product or processes that create it are novel or different. Even though a second software project to write an accounts payable system is very similar to the first such project, there will be some differences, perhaps something as simple as the format of reports. The same is true of digging two ditches (the purpose or terrain may vary) or organizing two conventions (the sites or programs may differ), and so on. For example, while hotels may have similar layouts (“footprints”), the people and materials involved in the construction are different for each hotel.

- Projects are progressively elaborated. This means that a project proceeds in steps or stages. Most well-managed projects use a phased approach, where the project defines the phases according to its control needs. For example, real estate developers often acquire land speculatively and then put together deals to construct hotels, restaurants, and convention centers according to the needs of the local market. We will describe more on the project life cycle phase in Chapter 5 and later chapters.

A project is a temporary work effort that produces a unique result.

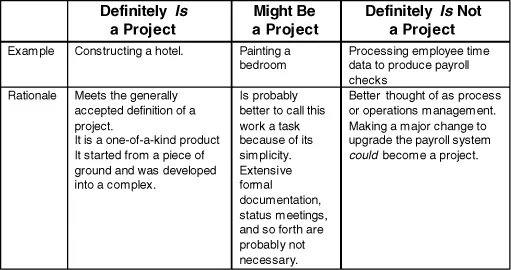

Now let us see how a typical organization might use this definition of projects as temporary, unique, and progressively elaborated to identify work activities that would best benefit from the project management tool set. Figure 1-1 shows three types of work that might take place in an organization. The first and third columns are straightforward. To define what something is, it is helpful to define what it isn’t. Let us look at the column headed, “Might Be a Project.” The “Might Be” column is important in addressing a common complaint about project management, which is project management is bureaucratic, involves many meetings, and so forth. The difference (and need for sophisticated project management) arises from the need to manage across interfaces and deal with complexity.

Why should you care about distinguishing projects versus nonprojects? Not everything individuals or organizations do is a project, but some things are a project. The things that are projects are typically not the day-to-day work of people but have to do with creating a new outcome. Projects are strategic! Because projects are complex and strategic, they require a particular and sophisticated set of managerial tools.

Not everything individuals or organizations do is a project, but some things are a project

While the term project refers to work activities, people also commonly use the term to refer to organizations of resources. Hence, projects perform work: After initiating the project, they “plan their work and work their plan,” make changes as necessary, and close out the project.

Contemporary thinking identifies projects as essential components of enterprise strategy. Projects are one important kind of organizational work because they create change. Because projects create change, good organizations explicitly align their projects with the investment policies and intention of management. We explore the selection and definition of projects further in the next and subsequent chapter.

PROJECTS DISTINGUISHED FROM TASKS AND FROM PROCESSES

It is important to distinguish projects from other kinds of work. A project is more complex than a task and more unique than a process. There are not clear-cut distinctions, and each individual and organization will develop and apply judgment on where and how to clarify the differences.

Projects are different for other work activities and require different tools.

Projects are more complex than tasks. For an individual, going to work on some mornings might seem to be a major undertaking. It is something that the individual must do in order to maintain employment, it requires resources, and it has a goal. The individual needs to apply some forethought to identify the best route considering the risks involved. He or she could even create a “to do” checklist for the undertaking to help him or her remember all the steps.

However, from the perspective of an enterprise, an individual’s commute to work is a task and not a project. It does not involve the coordination of people (although organizing a car pool could be an exception), does not require capital investment, and does not benefit from managerial oversight. In most organizations, a task is something that an individual can accomplish by himself or herself in a few hours or a few days of time.

While both projects and tasks have an end-state goal and use resources, there is little value in developing a project management approach for the task of going to work. We think it is important to include in the definition of a project—at least for purposes of this book—those endeavors where project management tools add value. There is no sense in adding the sophistication of project management tools for work that simply does not require sophistication.

We want to stress that project management is not managing your “to do” list. In Chapter 6, we again turn to the discussion of tasks but examine them as the activities that the project organizes into a work breakdown structure.

Some organizations fail to recognize the distinction between tasks and projects. An ad hoc approach is suitable for a task but not for a project. In these organizations, a mixture of effort and luck drives performance. Organizations get inconsistent results from their projects and tend to attribute the result (good or bad) to the individual. In the past 10 years, however, there has been a growing movement within the project management profession to measure and develop “project management maturity” systematically at the enterprise level. It is now much easier to identify the causes and consequences of successful project management.

Considerable progress has been made in identifying the factors that lead to successful project management.

Now let’s examine how projects differ from processes. Processes have three components: inputs, transformations, and outputs. From an organizational standpoint, processes are mostly repetitive and produce common outputs. Projects are different from processes because they have less consistency in inputs, transformations, and outputs. For example, if the individual’s project is to build an amplifier circuit, at some point, building a second, third, or fourth amplifier circuit ceases to be a project and becomes a repetitive activity. If each amplifier is virtually identical, we have a production line; thus we are managing a process, not a project. The lesson here is that the individual should determine if the requestor’s requirement is to build a single amplifier, or to build a batch of amplifiers, to build an amplifier production line. Often, the individual performs unwanted or unbudgeted work, a phenomenon known in the project management community as scope creep.

Refer back to the right-hand column of Figure 1-1. Other examples of processes are manufacturing, payroll processing, and building maintenance. Process management focuses on standardization, particularly of the output. To achieve consistent, high-quality, standardized outputs, process management places requirements on the inputs (the raw materials) and the production that transforms the inputs to the outputs. High-volume, high-quality output is typically a goal of process management.

The disciplines of “process management” and “project management” differ in goals and metrics. In process management, goals and metrics are set up to eliminate variation within the process because variation is wasteful. A new product...