eBook - ePub

Occupational Therapy in Orthopaedics and Trauma

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Occupational Therapy in Orthopaedics and Trauma

About this book

This book fills a gap in providing specialist information on orthopaedics and trauma occupational therapy. Its contributors bring together information on the aetiology, surgical input and the occupational therapy intervention appropriate to this client group. It is divided into two main sections, the first being orthopaedics and the second orthopaedic trauma. The first part is further subdivided to cover lower limb surgery, upper limb surgery, spinal conditions, and paediatric orthopaedic conditions. In Part two, principles of fracture management are covered, followed by pelvic and acetabular reconstruction, hand injuries and traumatic amputation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Orthopaedics

Chapter 1

Principles of orthopaedic surgery

Introduction

In this chapter we will explore some of the more recent developments in orthopaedic surgery, in particular, those aspects that form the basis of everyday practice. In recent years there has been a rapid expansion in the treatment options available to people with musculoskeletal disease. This has resulted from the development of safe anaesthesia, improved engineering of implant materials and refinement of surgical techniques. With this improvement, a greater emphasis has been placed on the person’s recovery from surgery which, in turn, has led to the development and importance of rehabilitation and the multi-disciplinary approach to people’s care.

History and early development

Orthopaedics derives from the Greek words ‘straight’ and ‘child’ and was a term described by Nicholas Andry (1658–1759) in his book Orthopaedia: or the Art of Correcting and Preventing Deformity. Much of the early practice of orthopaedics was concerned with the correction of deformity. More recently, as our population age has changed, the conditions that form part of our everyday practice have changed too. To mention all the important developments in the process of orthopaedic history would be exhausting, but some names of interest follow.

Ambroise Pare (1510–1590) was a prominent surgeon in France in the sixteenth century and published on anatomy and physiology and later on surgery. He described a number of surgical techniques relating to amputation such as the use of ligatures for large vessels, and tourniquets. He also designed a number of surgical instruments and artificial limbs. At times of conflict, limb amputations were common and often the only treatment for limb injury and deformity. Limb amputation skills were displayed with amazing speed and precision in experienced hands.

Antonius Mathysen (1805–1878) invented the plaster of Paris (POP) bandage which remains part of everyday orthopaedic and trauma practice. Little has changed in the principle of this form of splintage since its creation and only some of the indications have been altered to keep up with alternatives offered by surgery. Joseph Lister (1827–1912) became James Syme’s (of Syme amputation fame 1942) house surgeon and later married his daughter. While working as assistant surgeon to the Royal Infirmary in England he introduced antisepsis, which had a dramatic effect in reducing infection, and infection related mortality. This paved the way for further developments in surgical techniques and is a crucial part of successful surgery and specifically to orthopaedic surgery today. Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen (1845–1923) was a professor of Physics at Wurzburg and discovered roentgen rays (X-rays). The first radiograph taken was of his wife’s hand and this was allegedly offered to her as a Christmas present. Something he may not get away with today! In 1901 he received the Nobel prize for his work in this area.

Gathorne Robert Girdlestone (1881–1923) was the first professor of orthopaedics in Britain and has a long association with a number of prominent centres, including the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre in Oxford. His technique of excision arthroplasty of the femoral head is a procedure now used mainly as a salvage procedure after failed hip replacement and carries his name. Originally it was commonly used to treat hip tuberculosis prior to the advent of antibiotic therapy and joint replacement surgery. In 1942, an American, Austin Moore (1899–1963), performed and reported the first metallic hip replacement. Although it involved replacing the entire upper portion of the femur with a vitallium prosthesis, this was the start of a rapid development in better designs and techniques. Sir John Charnley (1911–1982) improved the design of the total hip replacement and was also involved with the development of self-curing acrylic cement. Many of the hip joint arthroplasties performed in the 1960s by him are still surviving well. It is open to debate as to whether his excellent design was luck or brilliance, but it was to form the benchmark for total hip replacements for the next 40 years.

Other centres such as Exeter have now proven results of joint replacement while those such as Birmingham are in the early stages of producing promising long-term results with newer designs. The Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty, designed by Derek McMinn and colleagues at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital in Birmingham in the early 1990s has had widespread interest due to a successful return to early design principles but now with better manufacturing techniques and better results. Other designs of this metal on metal resurfacing arthroplasty have followed and these types of replacement are now widely used throughout Europe, the USA and Canada.

Although huge strides have been made in the past century in the field of orthopaedics, it is expected that similar ongoing advances will continue to be made. Developments in cartilage replacement options hold promise as alternatives to joint replacement and there is continued development in the field of stem cell research. These and many others offer tremendous therapeutic options for an ever-increasing population of people with orthopaedic problems.

Prevention of infection

Prevention and management of infection in orthopaedic surgery has been one of the most important advances over the past century, which has allowed rapid development in our practice. Over 70% of hospital-acquired infections occur in people who have undergone surgery and these lead to considerable morbidity and rise in surgical costs. Treatment of infection in bone can be very difficult, and following implant surgery even more of a challenge, and so the prevention of infection is where we place a great deal of our efforts.

Definitions

- Decontamination – a process of removing microbial contaminants which can be carried out by cleaning, disinfection or sterilisation.

- Cleaning – a process that removes visible contaminants but does not necessarily destroy microorganisms.

- Disinfection – reduces the number of viable organisms to an acceptable level but may not inactivate some viruses, hardy organisms such as mycobacteria, or spores. A topical disinfectant that can be safely applied to epithelial tissue (like skin) is called an antiseptic.

- Sterilisation – this involves complete destruction of all viable microorganisms, including spores, viruses and mycobacteria. This may be accomplished by heat, radiation or chemical means and often the choice depends on the nature of the material being sterilised.

Prevention strategies

Handwashing has been shown to be the single most important method of controlling the transmission of hospital-acquired infection, as organisms are passed from one person to the next via staff caring for them. Washing the hands before and after physical contact with people and after activities where they are likely to become contaminated cannot be overemphasised.

Soaps, detergents or alcohol-based agents are now commonly provided in areas such as wards, clinics and outpatient departments where staff come into direct contact with people. A set of ‘universal precautions’ are typically taught and are available as a way of reminding staff of ways to prevent the transmission of infection. These include instructions on wearing gloves, dealing with wounds, sharp instruments and contaminated products. All staff should make themselves familiar with local policies and guidelines relating to these.

Screening of at-risk patient groups is important especially in the more controlled environment of planned or elective surgery. Organisms that can be detected and controlled, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), are important to detect prior to high-risk surgery and particularly in implant surgery. It is advisable to isolate a person found to be carrying these organisms so as to prevent the transmission to other people in the ward.

Antibiotics are used routinely in implant surgery and have been shown to reduce the risk of postoperative wound and deep infection. Broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotics given prior to starting the surgical procedure are required for implant surgery and the choice of antibiotics is often dependent on local microbiological guidelines. The widespread use of antibiotics in all clinical settings, however, has led to certain organisms becoming resistant to various agents, for example:

- MRSA

- Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA)

- Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (VRSE).

The appropriate use of antibiotics, however, is an essential part of prevention of infection in orthopaedic surgery.

Theatre strategies include sterile gowns, drapes, double gloves, and the use of masks and caps. Air-borne bacteria are a source of postoperative sepsis and now laminar-flow ventilation systems in theatres are becoming the norm to supply ultra-filtered air to the operative field and thereby reduce infection. Evidence exists to show that the use of ultra-clean air conditions will reduce the incidence of deep periarticular infections by half (from 3.4% to 1.6%). The addition of antibiotics will further reduce this to 0.19%. This is of particular benefit in prosthetic implant surgery (Lidwell et al. 1987).

All staff in contact with the operative field or instruments involved in surgery are required to disinfect their hands prior to placing sterile gloves on for surgery. This is aimed at reducing the volume of viable organisms, which may otherwise contribute to postoperative infection. A number of preparations are available, and many are alcohol or iodine based.

The surgical area is prepared with an antiseptic solution and care is taken that nothing contaminates this during surgery. Sterile drapes are used and all instruments used are sterilised to ensure no viable organisms are likely to contaminate the operative field.

Main conditions, diagnosis and treatment principles

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a non-inflammatory degenerative joint disease. It is characterised by loss of articular cartilage and associated with new bone formation and capsular fibrosis that results when chondrocytes fail to repair damaged cartilage. The causes fit into two broad groups:

- Primary/idiopathic – no obvious cause

- Secondary – identifiable cause:

– Previous trauma

– Congenital deformity

– Infection

– Metabolic disorders.

Typically this condition is progressive and results in pain and stiffness in the joint involved. This may lead to:

- Alteration of limb length

- Fixed deformity in the joint limiting movement

- Progressive wasting of muscles as the limb is used less.

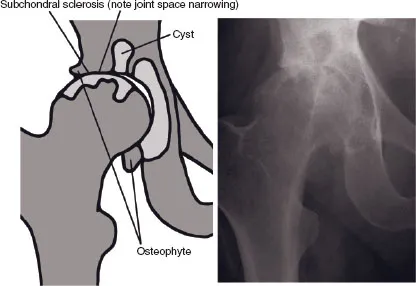

People who experience symptoms and signs of non-inflammatory arthritis have the clinical diagnosis confirmed with X-rays. Radiological signs include (Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1 Radiological signs of osteoarthritis.

- Joint space narrowing – initially at maximal load area before progressing to the entire joint

- Development of osteophytes as the joint endeavours to repair itself

- Subcortical/ subchondral sclerosis indicated by thickening of the bone below the joint surface

- Subchondral pseudo-cyst formation.

Initially treatment should always involve conservative/non-operative options. Once non-operative measures have been exhausted, surgery may be considered. The non-operative/ conservative measures recommended are:

- Protection of joint overload by achieving weight loss and using walking aids

- Exercise of supporting muscles to avoid wasting and prevent stiffness

- Pain relief in the form of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections

- Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections (Snibbe and Gambardella 2005)

- Glucosamine and chondroitin (Richy et al. 2003).

Operative measures (for people with persistent pain and symptoms despite conservative measures) include:

- Arthroplasty – unicompartmental or total joint arthroplasty

- Realignment osteotomies in younger persons.

Some treatments are being used but do not yet have convincing evidence to prove their benefit and at this stage should be considered experimental. For example, soft tissue grafts, such as:

- Chondrocyte transplants (Bentley et al. 2003)

- Mosaicplasty (Bentley et al. 2003)

- Fresh osteochondral grafts (Ma et al. 2004)

As this condition is such a large part of everyday practice in orthopaedics, it is also part of massive financial investment into newer forms of treatment, many of which do not have good evidence to prove their benefit. These do form an essential part of the on-going development of our practice but must be used in controlled environments and with caution.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease with an unclear aetiology and a number of joint sequelae. The symptoms are that of an inflammatory arthritis and typically the person experiences acute or chronic episodes throughout their life. Much of the treatment is aimed at controlling the condition and preventing the chronic changes usually associated with RA. Early aggress...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Orthopaedics

- Part II: Trauma

- Appendix: List of useful organisations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Occupational Therapy in Orthopaedics and Trauma by Madeleine Mooney, Claire Ireson, Madeleine Mooney,Claire Ireson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Beschäftigungstherapie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.