eBook - ePub

Organization Practice

A Guide to Understanding Human Service Organizations

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organization Practice

A Guide to Understanding Human Service Organizations

About this book

Human service organizations are under increasing pressure to demonstrate that their programs work. Organization Practice, Second Edition helps students and professionals in human services and nonprofit management understand complex behaviors in organizations. This new edition provides a new, practical model for understanding cultural identities within organizations. Also, it is significantly revised to include numerous real-world cases, critical thinking questions, empirical support, and engaging exercises. Social workers, as well as public health and nonprofit administrators will benefit from the insights in this book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organization Practice by Mary Katherine O'Connor,F. Ellen Netting in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

2Subtopic

Social PolicyPART I

STRUCTURE AND CONTROL

PART I FOCUSES on understanding practice within Traditional Organizations with goals of structure and control. The first chapter (Chapter 3) investigates theories that can be used to understand Traditional Organizations intent on maintaining and sustaining order. In Chapter 4, the focus switches to understanding practice in traditional human service organizations. Starting with the functionalist paradigmatic perspective, followed by a thorough look at the hierarchy culture, we will investigate the identities, values, preferences, standards, and strategies congruent with organizations holding structure and control goals.

In Chapter 3, approaches to understanding Traditional Organizations are introduced along with details of the underlying assumptions that form the Traditional Organization’s identity: that there are universal truths and that maintaining order and stability is most important in a turbulent environment. Classical, neoclassical, and “modern” structural organizational theories provide a historical perspective on functionalist assumptions that have been embraced by traditional human service organizations. Early human relations theories emanating from now-famous studies are reviewed in this chapter, because their original intent was to control workers and keep them focused on organizational goals rather than respond to their needs in any way. Two types of systems theory (mechanistic and organismic) are included with their focus on inputs, throughputs, outputs, and outcomes. Not all systems theories hold functionalist assumptions. Because of that, other types within the systems theory school will be reviewed in later chapters.

The content of Chapter 3 will likely seem familiar to the reader, as the majority of human service agencies have survived by at least attempting to articulate conformity to assumptions in which maintaining the status quo is a high priority. Since Traditional Organizations are designed to resist change, there are costs as well as benefits. Both will be examined.

In Chapter 4, the focus switches to understanding practice in traditional human service organizations. Using the lens of strategic management and the roles of managers and leaders within the hierarchical culture, important dimensions of practice will be explored. Here we will examine programming, management, research, accountability, relationships, prescriptive planning, and paradox, along with the type of advocacy most often used where structure and control are goals. It will become clear that practice in organizations having traditional perspectives fits well with the current push toward outcome and performance-based measurement, which assumes that if one does certain things on the front end (inputs), and then knows what technologies to use with clients (throughputs), one can select predetermined measurements for the quality of what happens (outcomes). Further, there is congruence with the belief that the only worthwhile outcomes are those that are measurable. This chapter demonstrates why planned change approaches in which incremental change is appropriate also work well with hierarchical cultures, as do research methods dedicated to theory building and testing. Discussion of the paradoxical nature of measurement within organizations where individual change is the output is also included in keeping with our discussion in earlier chapters on critical thinking, self-awareness, and multiculturalism. End-of-chapter discussion questions and activities are aimed at enhancing readers’ critical thinking about understanding and practicing in traditional, bureaucratic human service organizations with established and legitimized identities and reputations.

To introduce our focus on traditional human service organizations with goals of structure and control, we begin with a case example. In the next two chapters, you will see the structure and behavior standards within this type of organization, so that as the text unfolds you will come to understand how this perspective differs from what will follow in the rest of the text.

The Washington County Office on Aging

The Washington County Office on Aging came into being in the late 1970s as small allotments of Title III funds from the Older Americans Act trickled down to the grassroots level. Jayne remembers it well, because she was just graduating from her master’s program, hoping to find a job. Having worked for the Central Capital Area Agency on Aging (AAA) as a field intern, she had watched as each of eight counties conducted a search to hire a qualified professional to head up their county offices. It was her good fortune to graduate just in time to capture the directorship of the office in Washington County.

The AAA was housed in a regional health and human services planning and development district office, and the director had developed a very organized way to approach the distribution of federal aging dollars. Even though funds were limited, there was just enough to hire a director for an office on aging in each county as long as the county judge and county commission (later called the county executive and board of supervisors) gave their approval and offered matching funds to sweeten the deal. All but one county jumped at the opportunity, and the one outlier was a mostly rural county with a county judge who was up on charges of drug possession. However, even with those localized problems, that county had replaced the judge and gradually followed the pattern already established by the other seven counties.

Jayne remembers vividly the beginnings of the county office. Her first day at work found her stumbling over the cinderblock steps that had been stacked in front of the old nurses’ building behind the county hospital. The nurses’ building was to become the county’s first senior citizens’ center and the office on aging would serve the dual purpose of center oversight and management as well as establishing the home and community-based service programs to be offered through the countywide office. It was very comforting for Jayne as a newly minted graduate to have directions from the Area Agency on Aging that had been standardized in a Director on Aging job description, an organizational chart showing the relationship of the director to the county and the county to the AAA, guidelines for establishing an advisory council of senior citizens, and requests for proposals (RFPs) to apply for state funding for the senior citizens’ center. She remembers thinking that her work was cut out for her, but she didn’t have to worry about how to begin, because the directives were clearly stated. First, she wanted to meet with Judge Bill Reynolds, her new supervisor, and ask him about county priorities. Next, she would identify older citizens who would be a part of the advisory council. Finally, she would tackle responding to the RFPs. If those funds could be secured, it would mean that the office would have a mix of federal, state, and county funds in the budget.

Jayne’s early recollections about the Office on Aging were fond memories of her first position out of school. She stayed in that position for five years, then moved out of town for another position in the aging network. But she was proud to leave things in good order. In fact, her organizational skills were appreciated by the older persons with whom she worked in Washington County, and she had provided leadership in obtaining additional federal dollars as well as secured an operational budget for the senior citizens’ center prior to her departure. The renovation of the senior center had taken place with county funds and the county judge had convinced the commissioners to make the office on aging a continuing line item in the budget. Jayne had designed a brochure that explained how the office on aging worked, outlined the services provided, and advertised the senior center’s activities. This brochure had been adopted (with local modifications) in the other seven counties, so that a senior citizen who moved between counties would know exactly what to expect in an adjacent county. One of the things Jayne enjoyed most was talking with senior citizens groups and explaining just how the “aging network” was organized.

Over the years, the offices on aging witnessed turnover in staff in all but one of the offices in the eight counties. With each transition, the AAA staff would provide each new employee with copies of brochures and other public relations information, organizational charts, copies of funded grant proposals to use as examples, pertinent regulations tied to the Older Americans Act, state regulations on senior center operations, and a packet of forms used in all the counties. In recent years, the forms were being sent electronically and completed online. With each office completing the same forms, comparable data were available in the AAA’s information system and a report card could be given to each county office. In this way, the director could see how their operation shaped up in comparison with their peers in other counties. This had led to a bit of competition between the offices over the years.

The Central Capital Council on Aging, a regional group, had developed into a force to be reckoned with over the years. Each of the eight county councils on aging elected two delegates to go to the monthly meetings of this regional body. The directors of the offices on aging, the directors of the senior citizens center, and their delegates arrived at these meetings every month and listened to the AAA director and his staff detail any changes in rules, regulations, or protocols. Delegates would take back what they learned to the local councils, keeping everyone informed of the latest political, economic, social, and technological developments. Every year, at the annual meeting, each delegation would report on progress made that year and make any amendments to their county plan. The AAA would then incorporate any changes into its area plan and share the results with the eight counties.

Jayne visited the Washington County Office on Aging periodically when she was in the area. What she liked about her visits was that she could count on some degree of familiarity with what was going on and, therefore, catch up fairly easily. The senior citizens center had grown a great deal over the years and the activities were more diverse than the earlier days, with more groups scheduled to meet at the center. The quilting frames that had dominated the large meeting room had been replaced by an exercise room format, and the activity chart was no longer in paper copy. It was posted on an electronic bulletin board that dominated the view as one came into the lobby. During her last visit, a public forum was being held to gather needs assessment data for the upcoming three-year plan, and issues of transportation, home health care, and nutrition were being discussed. The AAA staff kept emphasizing the importance of effectiveness-based programming and the need for clear, measurable outcome objectives to be stated. She knew that the Washington County Council on Aging members would be preparing their input to take to the regional meeting and that soon a plan would be distributed (complete with process and outcome objectives, as well as action steps), ready for another year.

CHAPTER 3

Traditional Organizations

IN CHAPTER 2, we introduced the Functionalist Paradigm and Traditional Organizations, and in this chapter we deepen that original discussion by exploring what constitute appropriate structures of organizations holding this perspective on appropriate goals for organizing. We start by investigating the themes found in functionalist thinking and the assumptions that constitute the Functionalist Paradigm, resulting in the structure and control goals of what we are calling the Traditional Organization. Following this paradigmatic discussion, the major theories that fit within this perspective are identified. To add to our investigation of Traditional Organizations, we will draw on the Washington County Office on Aging as an example. We close this chapter with a critical analysis, so that the reader is left with the ability to judge what is gained and what is given up when approaching organizations from a functionalist worldview. We then transition to Chapter 4, which focuses on the culture and the behavioral theories that guide the standards of practice within organizations with structure and control goals. Of the four types of organizations, we begin with the most familiar and traditional views of organizations, because they are generally assumed to be the gold standard of organizing, although many other competent approaches have developed as worldviews and organizational theories have become more complex.

We want to caution the reader that we are referring to the Traditional Organization as a prototype, because today there may no longer be “pure” Traditional Organizations. Even agencies that are definitely functionalist in nature may have units, programs, and/or staff members that operate under different assumptions. For example, Jayne did observe when she returned to visit the Washington County Office on Aging that one of their newest programs had been designed by volunteers and was not quite the same as the other programs. The volunteer-caregiver program was much more loosely structured and was heavily volunteer run and operated. Volunteers were meeting on a regular basis, often without paid staff involved in the decision-making process. The director had privately expressed some concern about not feeling “on top of” what they were doing. Jayne was curious to see how this program would fit within what traditionally had been a hierarchical structure controlled by paid staff members. When something such as what Jayne noticed happens, organizational members and units will encounter paradoxes as differing assumptions clash. As you read further into the book, it is our hope that you will understand why functionalist assumptions may collide with assumptions from other paradigms. But, first, let’s focus on the themes and assumptions of the Traditional Organization.

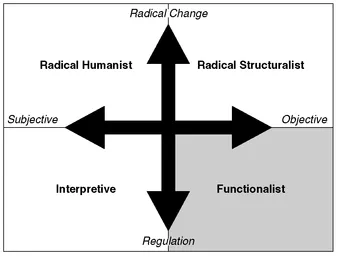

Figure 3.1 Burrell and Morgan’s Paradigmatic Framework Source: Adapted from Burrell and Morgan (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. Aldershot, England: Ashgate. Figure 3.1, p. 22. Used by permission.

Recall from Chapter 2 that Traditional Organizations count on stability and control to assure that programs run smoothly. There is attention to and appreciation of history and tradition, along with objective sources, to design, develop, and evaluate organizational activities. Activities are undertaken with a division of labor achieved through well-defined organizational and programmatic structures that are usually hierarchical with clear lines of authority with promise for efficient and effective practices. Figure 3.1 shows where the Traditional Organization fits within the paradigms introduced in Chapter 2.

FUNCTIONIALIST THEMES

Most traditional approaches to understanding organizations are based on assumptions held within the boundaries of the Functionalist Paradigm. Additionally, most of the theories that were developed during the early stages of organizational research are positivist and, therefore, functionalist in nature. These theories are based on the presumption that research and analysis of organizational data are exclusively rational and research methods should be traditionally scientific. Therefore, organizational study should be oriented to carefully defined designs, including variables, sample, data collection, and data analysis. Further, there is an assumption that good organizational study is impersonal with the goal of prediction and control of persons and things within the organizational setting. Functionalist theories “seek to search for regularities and attempt to test for the existence of such regularities in order to predict and control organizational behavior” (Vibert, 2004, p. 12). Research is capable of producing generalized principles to guide the replicability of events and procedures in the organizational context. Once there is sufficient evidence, then it is possible to know enough about the organization to control both the process and the product of the organization. With sufficient information, order can be structured and activities within the organization can be regulated in a predictable manner.

The Washington County Office on Aging is an excellent exemplar of these functionalist themes. Each of the eight county offices had the same basic goals and was designed to resemble the others. As the years progressed, these offices collected the same data and those data became the information system for the region. No one ever questioned whether the data collected were the most relevant to the individual county’s needs, because the standard was uniformity across offices.

Functionalism holds a traditional view of knowledge building about organizations that has its genesis in the natural sciences, where controlled experiments are the preferred method of knowing and understanding. This expectation and the assumptions on which it is built present challenges for research and practice in ever-changing, complex organizations where all the variables may not be known and order is not part of the organizing experience. To more fully understand these challenges, it is helpful to look more closely at the basic terms and assumptions that define the paradigm.

ASSUMPTIONS OF THE FUNCTIONALIST PARADIGM

The Functionalist Paradigm is objectivist in its perspective. Recall that in Chapter 2 we presented four terms that define objectivism. Box 3.1 provides a brief review of those terms.

The functionalist perspective assumes there is reality apart from the individual and his or her perceptions, and that there are universal truths. The functionalist ontology is realist, assuming that what is known is independent of the human mind and that understanding anything is abstracted from an independent reality that exists “o...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- ORIENTATION AND OVERVIEW

- PART I - STRUCTURE AND CONTROL

- PART II - CONSCIOUSNESS RAISING FOR CHANGE

- PART III - CONNECTION AND COLLABORATION

- PART IV - INDIVIDUAL EMPOWERMENT

- CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX A - Organization Assessment

- Glossary

- References

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX