![]()

Part One

Leadership Development and Selection

![]()

Chapter One

Best Practices in Leader Selection

Ann Howard

Getting the right leader in the top position stimulates organizations to prosper and grow. Chief executive officers (CEOs) account for 14 percent of the variance in organizational performance,1 which means that there is a huge payoff if selection is done right. Moreover, it can cost millions of dollars if it’s done wrong.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of CEO failures; estimates range from 30 percent to 50 percent.2 A Booz Allen Hamilton study found that the rate of CEO dismissals in the world’s 2,500 largest public companies increased by 170 percent from 1995 to 2003. Nearly one-third of the CEOs departing in 2003 (3 percent of a total of 9.5 percent) were fired for poor performance.3 Given these failure rates, it is not surprising that confidence in leaders is often shaky. In one national survey of public opinion based on 1,300 interviews, the average level of overall confidence in business leaders was 2.78 on a 4-point scale.4

The problem of poorly selected leaders could worsen as the Baby Boom generation retires, the supply of quality candidates dwindles, and the competition for talent heats up. Surveys have found that human resource (HR) professionals anticipated greater difficulty filling leadership positions in the future. The higher the management level, the more difficulty expected: 66 percent of respondents expected more problems filling senior leadership positions compared to 52 percent for mid-level and 28 percent for first-level leader positions.5

There are multiple reasons why senior-level positions are so difficult to fill. The skill requirements for top-level jobs are high, as are the risks, evidenced by the excessive CEO failure rate. Detracting from the job are competitive pressures from a fast-moving global economy and elevated visibility and surveillance. CEOs and boards are now scrutinized intensely by shareholders, regulators, politicians, and the legal system, and their specific decisions are being second-guessed.6 At the same time the pool of qualified, well-prepared candidates for top-level jobs has shrunk with the evaporation of many preparatory mid-level positions and organizations’ neglect of thoughtful succession planning.

This chapter describes how to get leader selection right. It reviews the objectives of selection, describes current selection techniques and evidence about their efficacy, and looks at how individual selection methods can be combined into an effective selection system. The chapter draws from general selection research and provides specifics for leaders where available.

OBJECTIVES OF LEADER SELECTION

Purposes of Selection

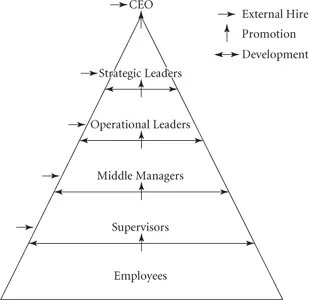

Although selection is usually thought of as hiring from the outside, internal selection (hiring from within) is just as prevalent for leaders. In addition to promotions, candidates are selected into positions or programs for career development and succession planning. Figure 1.1 shows some of the points at which leader selection occurs.

Recruitment of candidates varies by purpose and by management level. Entry-level leaders are usually a mix of outside hires and internal promotions. Organizations often place recruits from college campuses in first-level positions as an introduction to management roles. A classic pitfall of internal promotions is the selection of the best producer or technical performer, who is not necessarily the best manager. Such an ill-considered promotion leaves the organization with a mediocre leader and without a top performer.

Middle managers are traditionally brought up from the lower-management ranks. Selection for career development can occur at any management level, but succession management programs are usually aimed at higher levels. External hiring is common for a CEO, particularly if the organization is in trouble or is moving in a new direction. Outsiders run more than a third (37 percent) of the Fortune 1,000 companies, according to public affairs firm Burson-Marsteller, while insiders preside over the other two-thirds.7

Criteria for Selection Systems

Some might believe that the ultimate measure of a selection system’s value is organizational effectiveness. However, such a criterion confuses performance or behavior with results. Organizational effectiveness is determined by multiple factors that are beyond the control of an individual leader. These factors can be internal, such as production delays or a labor dispute, or external, such as competition and market conditions. As noted in the introduction to this chapter, a leader, particularly at high levels, can have substantial impact on organizational performance. However, organizational effectiveness is determined by more than a leader selection system.8

Criteria for measuring selection system success are of two types. The first concerns the output of the system, the most important of which is the individual performance of those selected. Organizations want the selection process to produce high-quality people who are well suited to their positions, will perform their required tasks well, and will remain motivated and committed. The system should also provide information about selected candidates that will prepare them and their managers for the growth and development that will inevitably be needed.

Additional criteria concern the nature of the selection system. It must be fair and appear fair to the candidates. It must work efficiently and remain viable over time. Each of these criteria warrants further exploration.

INDIVIDUAL PERFORMANCE

How well selected candidates perform in their new positions is the most important measure of selection system success. But there is more complexity in measuring the performance of leaders than that of individual contributors. A leader gets things accomplished through other people, so an important consideration is how leaders affect their work team and others in the organization. Thus satisfaction, retention, and performance of leaders’ direct reports can add important data to the evaluation of leader quality.

There are three primary categories of things needed for success on a job.9 These include declarative knowledge (knowledge about facts or things; knowing what to do), procedural knowledge and skill (knowing how to perform a task), and motivation (whether to expend effort, how much effort to expend, and persistence in that effort). The first two components are often called “can do” factors, while the latter is called the “will do” factor.

Traditional research has focused more on the “can do” than the “will do.” Yet high-quality hires will have little impact on organizational effectiveness unless they are motivated to stay with the organization long enough to make a difference. On average, managers stay in one organization 9.9 years,10 although this rate varies with economic conditions.

There is less research on the relationship between selection methods and attachment, whether measured as turnover, absences, or commitment. Factors other than the accuracy of selection come into play with these outcomes. Common causes of turnover are personal reasons, such as getting married or returning to school, and undesirable behavior by one’s manager. In fact, satisfaction has been equated to satisfaction with one’s supervisor.11 Research is sparse on selection methods and leader satisfaction, although this is an important precursor to retention.12

INFORMING INDIVIDUAL DEVELOPMENT

A chosen leader will seldom be perfect, and a sound selection system should also identify individuals’ relative strengths and development needs. For example, a leader might be strong in business management skills like operational decision making or financial acumen but need development in interpersonal skills such as building strategic relationships. For internal selection, information about what characteristics need strengthening are an essential part of the process, not only for those who are selected, but also for those not selected who want to try again. The shoring-up process, for knowledge as well as skill development, can come in the form of training, coaching, or a critical assignment.

Many organizations also want an external hire’s on-boarding process to include a development plan to work on needed skills and abilities. This requires the selection method to provide fodder for development—specific information that the new leader and his or her manager can follow to establish development steps. Jump-starting development could be an important factor in retention. When asked to choose the one most important reason employees leave, respondents most often cited a lack of growth and development opportunities (chosen by 25.3 percent). Only 8.3 percent chose a poor relationship with the manager.13 This suggests that employees endure a certain level of dissatisfaction with their managers as long as there are opportunities for growth.

LEGAL DEFENSIBILITY

Civil rights legislation and subsequent court cases have emphasized the importance of equal opportunity and the need for selection methods to be unbiased. Selection methods that produce adverse impact—defined as a selection rate for protected groups that is less than four-fifths (80 percent) of the rate for the highest group—must have clear evidence of job relevance and demonstrate that alternative methods are not feasible. This does not negate the use of methods with high adverse impact, but it makes them more subject to scrutiny.

CANDIDATE ACCEPTANCE

Selection is a two-way relationship, and there are consequences if a method affects candidates negatively. Candidates want to feel that their true skills, abilities, and potential are being evaluated and that they are being treated fairly relative to other candidates. Negative reactions are a particular concern to organizations because good candidates might withdraw from the competition and/or harbor negative feelings about the organization.

Unfortunately, research on candidate acceptance has seldom included leaders.14 While those at lower levels expect and accept a more high-tech, high-volume selection approach like online screening and testing, C-level (chief or highest-level executives) candidates often feel that they are above standard methods of testing or assessment and that their prior performance should speak for itself.15

In the past few decades, boards of directors often employed executive search firms to locate and screen new CEOs. The exact methods for selection were secret and probably idiosyncratic, but search firms commonly use unstructured interviews along with reference checks. As will be shown, these methods, though accepta...