![]()

Part One

SIMPLE MATRIX ORGANIZATIONS

In the Introduction, we saw several types of matrix structures. In this first part of the book, we will explore more deeply the simple or two-dimensional structure. This type was the first to emerge out of the aerospace industry in the 1960s and the R&D labs in the 1970s. There have been several variations of the simple type that have emerged for different circumstances. We will examine them in the first three chapters of this part. Chapter One covers the standard matrix design that was illustrated in Figure I.1. We will look at several examples of this standard type for the different types of applications where it has been used.

The next two chapters present two variations on the standard matrix theme. The first is the two-hat model. Some organizations cannot afford the overhead of having a set of vice presidents for functions and another set for products. But because the company still wants a dual focus, it uses the two-hat model, which has one set of vice presidents, each of whom wears two hats. That is, each vice president is responsible for a function and for a product. Sometimes the two-hat model is a transition step, and sometimes it is the model that is used to run a matrix organization. Chapter Two describes the model used by Chrysler before its acquisition by Daimler-Benz.

Another variation on the two-dimensional matrix is the baton pass model, described in Chapter Three. The model is used when there are long product development and life cycles. An example is in consumer packaged goods, with such brands as Kraft mayonnaise or Colgate toothpaste. They will go through cycles in which a new generation of product is created and launched. After launch there is the full implementation to all countries and through all channels. After several years, the product is renewed and relaunched. During the renewal, the product team is led by a manager from R&D up until the launch. Then, during and after the launch, the leadership—the baton—is passed to a product manager in marketing. During the next cycle, the baton is passed again to the manager in R&D. In the pharmaceutical industry there are longer cycles. There is a leader and a team in discovery, which hands off to another leader and team in development, which runs the clinical trials. At launch the product responsibility is passed to a third leader and team to realize the demand in all countries. So there are three teams and two baton passes. The pharmaceutical example is described in Chapter Three.

Chapter Four focuses on the situation in which a matrix is replicated at successive levels of the structure. This situation is referred to as the matrix within a matrix. For example, there is a CFO role at the corporate center, at the second level of the international division, and also at the third or country level. There will be a matrix at the international and the country levels for the finance function. Some of the alternatives are explored in the chapter.

The design of the two-dimensional matrix is intended to achieve a power balance between the two dimensions. In reality it is not necessary to achieve a razor’s-edge balance. A rough balance will usually suffice. But what is necessary is for the leader to have the skill to change the power situation to continually maintain the balance. Chapter Five describes the various power levers that the leader can control and should master. One of the levers is the responsibility chart, which can be used to change decision rights across the matrix. The chapter describes the use of the charts in detail.

In Part Two, I describe the more complex matrix designs—three-dimensional or four-dimensional structures, as well as structures with even more dimensions.

![]()

1

SIMPLE MATRIX STRUCTURES

In this first chapter, we focus on the two-dimensional matrix structure. This two-dimensional model was the first to appear and is still a frequently occurring structure. In its first appearance, the two-dimensional model was not even called a matrix. It was referred to as the line-and-staff model. But as the model was used in aerospace in the 1960s and in R&D labs in the 1970s, the term matrix was applied. The term has been used for all two-dimensional models ever since. We begin our discussion with a number of different applications.

Two-Dimensional Structures

The two-dimensional structure arises frequently in all organizations. We have already seen one example of an R&D lab in Figure I.1 in the Introduction. In the next section, we discuss the typical corporate function-profit center matrix that is common to all corporate centers. Despite a long history, this application can still generate arguments about who has the solid line and who has the dotted line. We will use this example to discuss the phenomenon of dotted lines.

The next example is of a sales organization. Sales today is one of the most complex organizations in the company. We will start with the simple geographic and national account matrix structure.

Corporate Functions

No matter what the profit centers are in a company, there is the usual matrix of corporate functions and profit centers. These profit centers could form a regional structure (Nestlé), a customer segment structure (American Express), or a business unit structure (United Technologies). In all cases, there is at least a finance function led by the chief financial officer (CFO) who reports to the CEO, and finance leaders who report to the profit-and-loss (P&L) leaders as well as the CFO. The labels may vary, but there will be such other functions as HR, legal, strategy, and external affairs, which are structured in the same way.

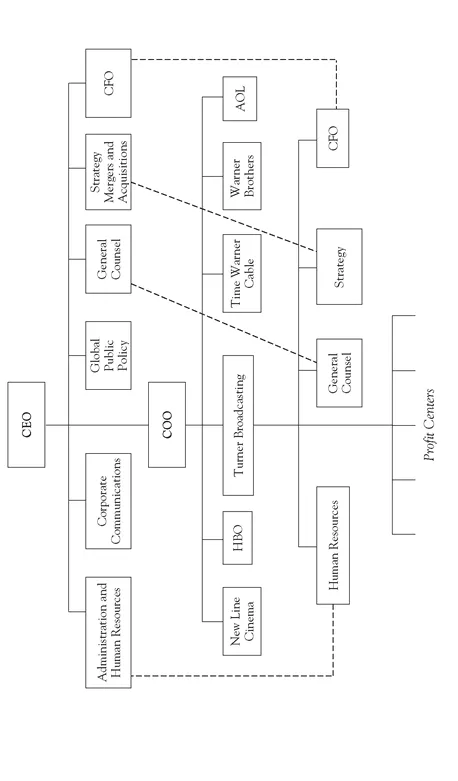

There might be just a few functions, as in a holding company or conglomerate structure, or many, as in a related divisional structure. Figure 1.1 shows the Time Warner (TW) structure. TW operates as a holding company with very independent businesses. The holding company corporate center contains just a few corporate functions. These functions have a dotted-line relationship with their counterparts in the businesses. That is, the functions in the businesses report first to the business unit manager (“solid line”) and second to the corporate function (“dotted line”).

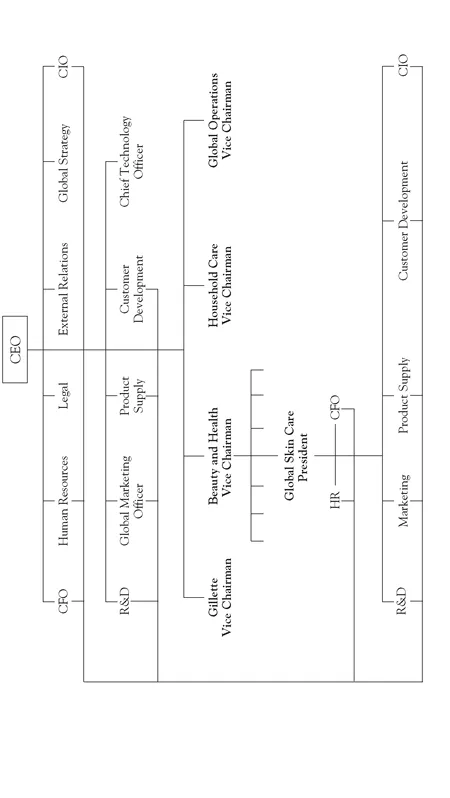

The Procter and Gamble (P&G) structure is a contrast to the TW structure. P&G has numerous corporate functions that play a strong role in the conduct of the enterprise. The P&G corporate structure is shown in Figure 1.2. P&G has the same standard corporate functions (HR, CFO, strategy, legal, external affairs) as TW. These functions are standard in both holding companies and divisionalized companies. But P&G also has corporate functions for the operating functions that make up the business units. These units set policy for the function, take ownership for key processes, plan for the future development of the function, and take responsibility for the assignment and development of the functional talent. The P&G corporate functions play a much more influential role than the corporate functions play in a holding company.

The top structure at P&G can be easily determined from the listing of corporate officers in the company’s annual report. However, P&G does not publish organization charts showing dotted and solid lines. At least I have never seen one. Nor have I heard people talk about solid or dotted-line reporting. So I asked one of my contacts at P&G about how they handle dotted and solid lines. He said, “The last time I even asked one of my two bosses which line was solid and which was dotted, he glared at me and growled ‘They’re both solid!!’ That was about twenty years ago, and I haven’t asked since.” Today people refer to their line boss and their functional boss. Their line boss gives the performance reviews and operational direction. The functional boss is responsible for career development and functional direction. From my point of view, this is a healthy practice. Enormous amounts of time can be wasted in debates about reporting relationships. I have never seen a change from solid to dotted or vice versa solve the CEO’s problem. It only changes which boss is the one who gets upset. It is clearly a win-lose discussion. I much prefer to use responsibility charts (Chapter Five) and shared goals (Chapter Ten). But many companies still insist on using the dotted and solid line convention. It is a holdover from the original line-and-staff days.

Figure 1.1: Time Warner Corporate Matrix Structure (Holding Company)

Figure 1.2: Procter & Gamble Corporate Matrix Structure

These corporate functions were initially called staff roles, which meant that they had no formal authority. Over time, however, it was recognized that these roles were often very influential. The roles had power and influence, but could not have the type of power that we call authority. It was always preferred to maintain the principle of unity of command. At some point, the convention arose that staff roles had a dotted-line relationship to their staff colleagues working for the profit center leaders. The profit centers or line organization had a solid line or authority relationship with those same staff functional roles. The solid line came to mean that the line manager was the real boss. So if there was a conflict between the staff leader’s direction and the line leader’s direction, the subordinate should follow the solid-line boss’s view. Under this practice, the subordinate could be influenced by both bosses as long as there was no conflict. The solid line would then be used when there was a conflict.

A number of different practices have evolved over time for dealing with the two bosses. Today there are standard ways to talk about these practices. One was mentioned in the Introduction. Often the line boss will determine what activities will be performed and when they will be performed. The corporate functional boss will determine how the activities will be performed. This practice is useful, but there can still be conflicts. The solid line is again the conflict resolver. Other practices are used to maintain the power balance. One convention is that the dotted line goes to the boss with whom the subordinate is physically located. The solid line goes to the remote boss to compensate for the lack of day-to-day contact. Another convention is that the dotted line goes to the boss who has the responsibility for the subordinate’s next career move. The solid line to the other boss is to maintain the power balance.

In all cases in the past, the solid-line boss made the determination on performance and submitted the salary increase and bonus request. In many cases, the solid-line boss had to collect input from the dotted-line boss but still made the final performance recommendation. Today the performance and talent management decisions are being made by a group that might be referred to as the management development committee. The purpose is to arrive at a full and fair assessment of the employee’s performance (Chapter Twelve). Many of the practices that are implied by the solid line are being superseded by more modern and matrix-friendly practices. These will be discussed in later chapters.

Sales Organization Matrix

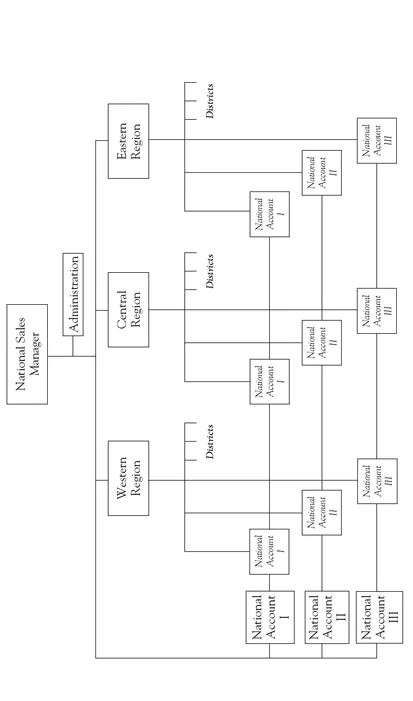

The matrix structure arises in many places throughout an organization. Figure 1.3 shows an example of a simple structure for a sales organization.

Sales organizations are usually regionally organized to minimize travel costs and have local salespeople call on local buyers. But there are often a few large national, even global, accounts. These customers ask for a single interface and often a single contract from their vendors. But these large accounts still need local salespeople to call on their national account’s local offices throughout the country. The result is a regional-national account matrix, as shown in Figure 1.3. It is a simple matrix because it has only two dimensions, regions and customer accounts, and there is only one level of organization between the two-boss manager—the national account representative in the region (shown here as national account I)—and the national sales manager who can resolve disputes.

Figure 1.3: Regional – National Account Matrix

This model is the simple matrix structure. Disputes can be raised rapidly through one level and quickly be resolved. There are two, not three or four, sides to the issues. The leader is usually in touch with the issues. If need be, the national sales manager can call everyone into a room, hold a face-to-face discussion, and arrive at a decision. If there are more levels, the decision process becomes more complex. It is harder to raise an issue through two levels to the leader, in this case the national sales manager. When more levels are involved, it is more likely that distorted and different versions of the issue will come to the leader. The leader gets farther away from the day-to-day issues. In a two-level organization, if the leader calls everyone in a room, about fifty people will probably show up. The leader can still call the nine people involved in a dispute if he or she can identify the right nine actors. You can still manage a two-level matrix. However, I always discourage companies from using more than two levels, particularly if the people are scattered around the world. It is just not worth the trouble. I have seen only a few three-level matrix structures that work effectively.

An overly layered structure can often be redesigned to reduce levels. Figure 1...