eBook - ePub

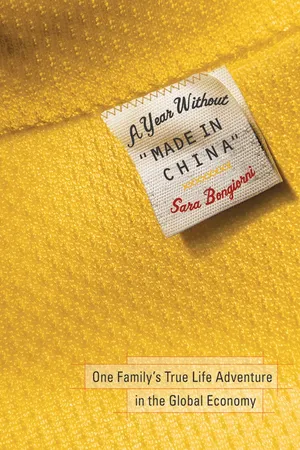

A Year Without "Made in China"

One Family's True Life Adventure in the Global Economy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Year Without "Made in China" provides you with a thought-provoking and thoroughly entertaining account of how the most populous nation on Earth influences almost every aspect of our daily lives. Drawing on her years as an award-winning journalist, author Sara Bongiorni fills this book with engaging stories and anecdotes of her family's attempt to outrun China's reach–by boycotting Chinese made products–and does a remarkable job of taking a decidedly big-picture issue and breaking it down to a personal level.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Year Without "Made in China" by Sara Bongiorni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & International Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Farewell, My Concubine

We kick China out of the house on a dark Monday, two days after Christmas, while the children are asleep upstairs. I don’t mean the country, of course, but pieces of plastic, cotton, and metal stamped with the words Made in China. We keep the bits of China that we already have but we stop bringing in any more.

The eviction is no fault of China’s. It has coated our lives with a cheerful veneer of cheap toys, gadgets, and shoes. Sometimes I worry about lost American jobs or nasty reports of human rights abuses, but price has trumped virtue at our house. We couldn’t resist what China was selling. But on this dark afternoon, a creeping unease washes over me as I sit on the sofa and survey the gloomy wreckage of the holiday. It seems impossible to have missed it before, yet it isn’t until now that I notice an irrefutable fact. China is taking over the place.

China emits a blue glow from the DVD player and glitters in the lights and glass balls on the drooping spruce in the corner of the living room. China itches at my feet with a pair of striped socks. It lies in a clumsy pile of Chinese shoes by the door, watches the world through the embroidered eyes of a redheaded doll, and entertains the dog with a Chinese chew toy. China casts a yellow circle of light from the lamp on the piano.

I slip off the sofa to begin a quick inventory, sorting our Christmas gifts into two stacks: China and non-China. The count comes to China 25, the world 14. It occurs to me that the children’s television specials need to update their geography. Santa’s elves don’t labor in snow-covered workshops at the top of the world but in torrid sweatshops more than 7,000 miles from our Gulf Coast home. Christmas, the day so many children dream of all year, is a Chinese holiday, provided you overlook an hour for church or to watch the Pope perform Mass on television. Somewhere along the way, things have gotten out of hand.

Suddenly I want China out.

It’s too late to banish China altogether. Getting rid of what we’ve already hauled up the front steps would leave the place as bare as the branches of the dying lemon tree in our front yard. Not only that, my husband Kevin would kill me. He’s a tolerant man, but he has his limits. And yet we are not cogs in a Chinese wheel, at least not yet. We can stop bringing China through the front door. We can hold up our hands and say no, thank you, we have had enough.

Kevin looks worried.

“I don’t think that’s possible,” he says, his eyes scanning the living room. “Not now, not with kids.”

He is nursing a cup of Chinese tea at the other end of the sofa. He hasn’t quite recovered from assembling our son’s new Chinese train, an epic process that lasted into the wee hours of Christmas morning. He looks a little pale and the two days of stubble on his cheeks aren’t helping. I have interrupted the silence to pitch my idea to him: for one year, starting on January first, we boycott Chinese products.

“No Chinese toys, no Chinese electronics, no Chinese clothes, no Chinese books, no Chinese television,” I say. “Nothing Chinese for one year, to see if it can be done. It could be our New Year’s resolution.”

He has been watching me with a noncommittal gaze. Now he takes a sip of tea, turns his head, and redirects his eyes to the bare wall on the opposite side of the living room. I had hoped for a quick sell, but I can see that this will take some doing.

“It will be like a scavenger hunt,” I suggest. “In reverse.”

Kevin is typically game to jam his thumb in the eye of conventional wisdom. The closest he came to a religious figure in his childhood was W.C. Fields. He would skip school to watch Fields in afternoon movies on the local channel out of Los Angeles. At 16, he took a year’s leave from high school and moved to Alaska for a job in a traveling carnival where he worked the dime toss and learned to speak carnie from the ex-cons who ran the rides. He returned to California, enrolled in community college, and spent eight years there, studying philosophy, gymnastics, and woodworking.

Kevin came by his rebel streak honestly. His father was a bitter teachers union organizer and political agitator who spent his weekends hiking nude in the Anza Borrego desert. I figure if I can tap into that rebel blood now, I can get Kevin on board for a China boycott.

“It can’t be that big a deal,” I tell him. “We don’t have a microwave. Our television has a thirteen-inch screen. With rabbit ears on top. Our friends think we’re nuts to live like we do, but I can’t see that we’re missing much. How hard can it be to give up China, too?”

Kevin keeps his eyes on the wall. I push on.

“We’re always complaining that the States don’t make anything any more,” I say, with a sweep of my arm. “We’ve said it a million times. You’ve said it a million times. Wouldn’t you like to find out for yourself if that’s really true?”

I see right away that the question is a mistake. Kevin lifts his brow and purses his lips in the exaggerated expression of a sad clown. I hear a soft rasp of air as he opens his mouth to speak, still not looking at me. I jump back in, quickly.

“We might save money,” I say.“Maybe we can finally stick to a budget, like we’ve been talking about for fifteen years. And it will be fun, sort of an adventure.”

I study Kevin’s profile. He has a square jaw and a nose that belongs on a movie star. But there is something wrong with his eyes. They have a glassy, faraway look and they are stuck on the scuffed green paint of the opposite wall. They can’t seem to turn my way.

I point out that my part-time job as a business writer means that I can do the heavy lifting when it comes to scouring the mall for merchandise from not-China. If there is anyone left in this busy world with time to waste, I say, it’s me.

“Not only that, I love reading those little labels that tell you where something is made,” I say. “You can leave that to me.”

Kevin may be too healthy to obsess over such details, but we both know that I am not. I have checked the labels on almost everything we own over the past couple of years. I take a perverse glee in tracking the downfall of the American empire by way of those little tags, which so infrequently bear the words Made in USA. It is the reason I know that we own a French frying pan, Brazilian bandages, and a Czech toilet seat. Those names were rare in our house. The one I spotted most frequently, maybe eight or nine times out of ten, was China. We would pause over the latest Chinese discovery, and then Kevin would say the words we both had on our minds: “Hell in a handbasket,” he would mutter with a shake of his head.

I wish now that I had not been so eager to share my Chinese findings with him. I need to get him to look past the obvious, that a China boycott is likely to turn our lives upside down. I need Kevin to set aside common sense, and personal experience, and plunge into uncharted territory with me.

“I’m not suggesting that we buy only American goods, just not things from China. And the kids, at one and four, are too little to know what they are missing. Can you imagine the howls if they were teenagers? If there is ever going to be a good time in this family for a China boycott, the time is now. And let’s be honest. If the checkbook sometimes dips into the single digits late in the month, it is due to a lack of money management skills, not a shortage of cash. Not everybody can afford a China boycott, but on your teaching salary and my writer’s pay, we can.”

At least I hope we can, I think.

“In any case, we can go back to our old ways next January,” I say. “China will be waiting for us. China will always be there to take us back.”

I check Kevin’s profile. He has decided to wait me out. It is his standard strategy, with good reason; it works nearly every time. When we disagree, he clams up, stands back, and lets me trip over my own feet. I remember seeing this same hazy look in his eyes, years ago, when I brought home a stray dog one afternoon and asked if we could keep it. Kevin paused at the front gate and said nothing. The beast sealed its fate when it erupted in snarls and charged Kevin, refusing to let him on the property. Kevin never uttered a word.

I see now that it’s time to pull out a big gun. I try to sound nonchalant.

“Some people said giving up Wal-Mart would be tough,” I say. “I can’t say we’ve missed a thing.”

At first, boycotting Wal-Mart seemed silly to me. I couldn’t see the difference between Wal-Mart and places like Kmart and Target when it came to issues like wiping out mom-and-pop stores and worker pay. True, I’d had a few unsavory personal experiences at the ancient Wal-Mart near our home. I had seen a man scream at an exhausted baby and on more than one occasion watched dying cockroaches pedal spiky legs into the air as I stood in the neon glare of the checkout line waiting to pay for underwear and diapers.

Then there were the standard reasons for picking on Wal-Mart—its bullying of suppliers and the blight on the landscape left by its abandoned stores, among other things. What got me on board for a Wal-Mart boycott was when I read that it barred labor inspectors from the foreign factories that churn out the $8 polo shirts and $11 dresses that hang on its racks. Even then, I could think of two nice things to say about Wal-Mart: It lets people sleep in their recreational vehicles in its parking lots, and it saves consumers collectively billions of dollars on everything from Tide to pickles.

It occurs to me that the Wal-Mart embargo is a good trial run for a China ban, since much of what it sells comes from China. I know this, because I read the labels on a lot of boxes at Wal-Mart in our pre-Wal-Mart-boycott days. Still, there is a key difference between a ban on Wal-Mart and one on Chinese goods. Ultimately, boycotting Wal-Mart requires just one thing: keeping your hands on the steering wheel and accelerating past the entrance to its vast parking lot. China, by comparison, blankets the shelves of retailers across the land, and not just the big-box stores but also perfumed boutiques and softly lit department stores and the pages of the catalogs that shimmy their way into millions of American mailboxes each day. China will not be so easily avoided.

I keep this last bit to myself. Besides, I can see that my Wal-Mart ploy has hit a nerve. The lines around Kevin’s mouth soften. His brow falls. He still has his eyes on the wall, but he is listening. A hostage negotiator would tell me I am making progress because I have him engaged. Keep him talking, the negotiator would tell me. Kevin had been slumped at the other end of the sofa but now he sits up and looks around the room. I try not to overplay my hand. I wait for him to make the next move. He turns his head and locks eyes with me.

“What about the coffeemaker?” he asks.

He is thinking about the broken machine that still sits on the kitchen counter despite brewing its last cup a month earlier. We picked it up at Target a couple of years ago. It was a memorable episode because it was the first time we noted China’s grip on the market for an ordinary household item. We stood in the aisle for 20 minutes, turning over boxes and looking at labels. Every box came from China. We shrugged and picked out a sleek black machine with an eight-cup pot. It sputtered to a halt one morning in November, but we left it sitting there, hoping it would somehow come back to life.

For weeks we have been boiling water and pouring it through a plastic filter on top of our coffee mugs. I don’t mind; it reminds me of camping trips to the mountains when we made coffee over the fire. But Kevin feels otherwise, and on cold mornings, when our kitchen takes on a cave-like chill and we are desperate for something hot, I can see his point. In asking about the coffeemaker, he wants to know if China is still fair territory in the search for a replacement.

“It’s December twenty-seventh,” I say. “You’ve got four days.”

Then I know I have him on board. He turns his head and looks over the chaos of the living room floor. He is making a mental list of other things he wants to add to our crowded household while he still has time. I say the place is half full but I can tell he would argue for half empty. I keep my mouth closed. This is no time to argue. In his mind he’s already making his shopping list and heading for the door, not once looking back. I picture a swirl of Chinese toy...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- CHAPTER ONE - Farewell, My Concubine

- CHAPTER TWO - Red Shoes

- CHAPTER THREE - Rise and China

- CHAPTER FOUR - Manufacturing Dissent

- CHAPTER FIVE - A Modest Proposal

- CHAPTER SIX - Mothers of Invention

- CHAPTER SEVEN - Summer of Discontent

- CHAPTER EIGHT - Red Tide

- CHAPTER NINE - China Dreams

- CHAPTER TEN - Meltdown

- CHAPTER ELEVEN - The China Season

- CHAPTER TWELVE - Road’s End

- EPILOGUE

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- INDEX