![]()

PART 1

THE FRAMEWORK OF HUMAN EVOLUTION

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE GROWTH OF THE EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE

OUR PLACE IN NATURE

As the train doors open at many stations on the London Underground, a disem-bodied voice can be heard saying “Mind the gap” to warn passengers that there is a larger than usual step between the train and the platform. This helpful announcement can act as a rather surprising motto for anyone about to embark on a course on human evolution.

KEY QUESTION How should evolutionary biology approach the problem of human uniqueness versus the continuities inherent in the evolutionary process?

The reason for this is very simple. If one asks the average person to come up with terms they associate with evolution, then after “survival of the fittest,” “progress” (of which more later), and “missing link,” another one that is highly likely to figure is “continuity.” Evolution is a continuous process, and so provides a link between all organisms in such a way as to place them all on a continuum, from the simplest single-cell organism to the most complex social mammal. Through evolution, plants and animals slide endlessly from one form to another. Continuity is therefore a major part of nature. However, the same average person, if asked whether there is a continuity between humans and other animals, is likely to answer no. Certainly there are many things that humans and other animals share, from their basic genetic code to the broad body plan of the vertebrate skeleton, but the gulf between humans and, say, chimpanzees, no matter how smart the latter appear to be, remains large, and to some unbridgeable. Humans are the species of Shakespeare and Dante, of Galileo and Einstein, of Wallace and Darwin, of Michelangelo and Picasso, of Beethoven and Bach; or alternatively, the species of Hitler and Stalin. No chimpanzee can come close to these sorts of achievements.

In the contrast between the continuity of evolution and the uniqueness of humans lies the challenge and interest of human evolution. It is the paradox that lies at the heart of the discipline – how is it possible to simultaneously “mind the gap” that exists between humans and other species and be true to the continuous nature of the evolutionary process? It is that challenge that has fueled much of the research into human evolution.

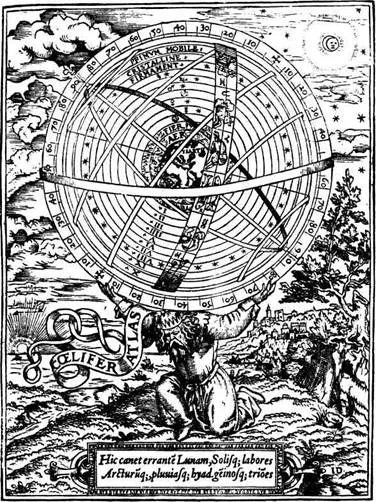

FIGURE 1.1 Ptolemy’s universe: Before the Copernican revolution in the sixteenth century, scholars’ views of the universe were based on the ideas of Aristotle as elaborated by Ptolemy. The Earth was seen as the center of the universe, with the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets fixed in concentric crystalline spheres circling it.

The problem of the gap has long been recognized. In 1859 Charles Darwin published his epoch-making book, The Origin of Species, in which he provided an account of how evolution worked, and how science might explain the patterns of life without recourse to supernatural beings and processes. While Darwin made little or no reference to humans, but confined himself to ordinary plants and animals, the implications were plain to see. Within four years his friend and supporter, Thomas Henry Huxley, published one of the first books on human evolution, Evidences as to Man’s Place in Nature. The book was based on evidence from comparative anatomy among apes and humans, embryology, and fossils of early humans (few were available at the time). Huxley’s conclusion – that humans have a close evolutionary relationship with the great apes, particularly the African apes – was a key element in a revolution in the history of Western philosophy: humans were to be seen as being a part of nature, no longer as apart from nature – hence the title of Huxley’s book. What both Darwin and Huxley, as well as many other scientists of that time, were keen to demonstrate was the continuity between humans and the rest of the biological world, and that all were the product of the same evolutionary processes. In other words, evolution underpinned the continuity of nature, including humans.1

Although Huxley was committed to the idea of the evolution of Homo sapiens from some type of ancestral ape, he nevertheless recognized that humans were a very special kind of animal. In his book he wrote:

No one is more strongly convinced than I am of the vastness of the gulf between … man and the brutes, for, he alone possesses the marvelous endowment of intelligible and rational speech [and] … stands raised upon it as on a mountain top, far above the level of his humble fellows, and transfigured from his grosser nature by reflecting, here and there, a ray from the infinite source of truth.2

Continuity and discontinuity

It is worth noting that the problem of continuity versus breaks in the chain of life is one that both continues through to the present day and existed in pre-evolutionary scientific thought. The reason for this goes back to the intellectual upheavals of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The revolution wrought by Darwin’s work was, in fact, the second of two such intellectual upheavals within the history of Western philosophy.3 The first revolution occurred three centuries earlier, when Nicolaus Copernicus replaced the geocentric model of the universe with a heliocentric model (Fig. 1.1). Although the Copernican revolution deposed humans from being the very center of all of God’s creation and transformed them into the occupants of a small planet orbiting in a vast universe, they nevertheless remained the pinnacle of God’s works. From the sixteenth through the mid-nineteenth centuries, those who studied humans and nature as a whole were coming close to the wonder of those works (Fig. 1.2).

This pursuit – known as natural philosophy – positioned science and religion in close harmony. What linked them was the notion of design.4,5 The living world could be seen to be admirably efficient and well organized, with each organism playing a role for which it was well suited. This was taken as evidence for a remarkable design, and consequently as evidence for a designer – in other words, the hand of God.

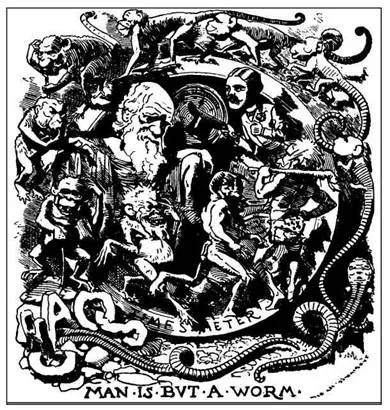

In addition to design, a second feature of God’s created world was a virtual continuum of form, from the lowest to the highest, with humans being near the very top, just a little lower than the angels. This continuum – known as the Great Chain of Being – was not a statement of dynamic relationships between organisms, reflecting historical connections and evolutionary derivations (Fig. 1.3). This focus on continuity, echoed in evolutionary ideas, was in fact one of the platforms on which Darwin built his theory. The difference between the pre-evolutionary idea of the Great Chain of Being and the later concept of an evolving lineage, though, is that the former was fixed. According to Stephen Jay Gould, the essence of the Chain of Being is the fixed positions of biological organisms in an ascending hierarchy.6

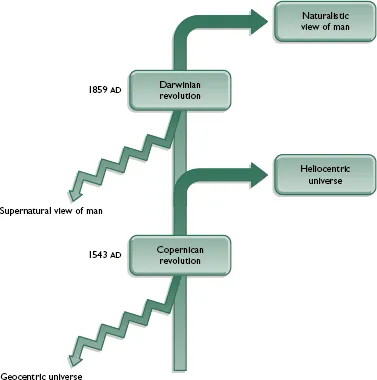

FIGURE 1.2 Two great intellectual revolutions: In the mid-sixteenth century the Polish mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus proposed a heliocentric rather than a geocentric view of the universe. “The Earth is not the center of all things celestial,” he said, “but instead is one of several planets circling a sun, which is one of many suns in the universe.” Three centuries later, in 1859, Charles Darwin further changed people’s view of themselves, arguing that humans were a part of nature, not apart from nature.

FIGURE 1.3 The Chain of Being: Both pre-evolutionary and early Darwinian perceptions of the relationship among living creatures involved the idea of a Chain of Being, or scala naturae, which implied a progressive development of greater complexity and change in the direction of humanity.

However, powerful though the Chain of Being theory was, it faced problems – as it happens, exactly the same problems as Huxley recognized, namely the gaps that occurred between certain parts of this Great Chain. One such discontinuity appeared between the world of plants and the world of animals. Another separated humans and apes.

Knowing that the gap between apes and humans should be filled, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century scientists tended to exaggerate the humanness of the apes while overstating the simianness of some of the “lower” races. For instance, some apes were “known” to walk upright, to carry off humans for slaves, and even to produce offspring after mating with humans. By the same token, some humans were “known” to be brutal savages, equipped with neither culture nor language. Basically, the natural philosophers were using the tales of sailors and the myths of the ancient world to fill in the gaps in their model scheme of creation.

This perception of the natural world inevitably became encompassed within the formal classification system, which was developed by Carolus Linnaeus in the mid-eighteenth century. In his Systema Naturae, published first in 1736 and finally in 1758, Linnaeus included not only Homo sapiens – the species to which we all belong – but also the little-known Homo troglodytes, which was said to be active only at night and to speak in hisses, and the even rarer Homo caudatus, which was known to possess a tail7 (Fig. 1.4).

Evolution and progress

In one sense the theory of evolution provided a solution to the difficulties faced by the natural philosophers, namely a better understanding of the dynamic nature of the links between the entities on the Great Chain of Being. The dynamism of evolution did not really remove the Great Chain, but added a new dimension to it – that of progress, which in turn provided an explanation for the hierarchy that many saw in both the natural world and humanity. For instance, humans were still regarded as being “above” other animals and endowed with special qualities – those of intelligence, spirituality, and moral judgment. And the gradation from “lower” races to “higher” races that had been part of the Great Chain of Being was now explained by the process of evolution.

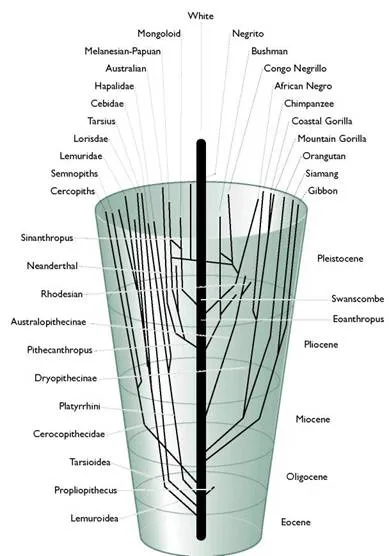

“The progress of the different races was unequal,” noted Roy Chapman Andrews, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History in the 1920s and 1930s. “Some developed into masters of the world at an incredible speed. But the Tasmanians … and the existing Australian aborigines lagged far behind, not much advanced beyond the stages of Neanderthal man.”8 Such overtly racist comments were echoed frequently in literature of the time and were reflected in the evolutionary trees published then (Fig. 1.5).

In other words, inequality of races – with blacks at the bottom and whites at the top – was explained away as the natural order of things: before 1859 as the product of God’s creation, and after 1859 as the product of evolution.

In the same vein, early discussions of human evolution incorporated the notion of progress, and specifically the inevitability of Homo sapiens as the ultimate aim of evolutionary trends. In the words of the prominent British anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith, written in 1927, “Progress – or what is the same thing, Evolution – is [Nature’s] religion,” 9,10 or, as Robert Broom put it in 1933, “Much of evolution looks as if it had been planned to result in man, and in other animals and plants to make the world a suitable place for him to dwell in.”11 (Broom was responsible for some of the more important early human fossil finds in south Africa during the 1930s and 1940s.)

FIGURE 1.4 The anthropomorpha of Linnaeus: In the mid-eighteenth century, when Linnaeus compiled his Systema Naturae, Western scientific knowledge about the apes of Asia and Africa was sketchy at best. Based on the tales of sea captains and other transient visitors, fanciful images of these creatures were created. Here, produced from a dissertation of Linnaeus’ student Hoppius, are four supposed “manlike apes,” some of which became species of Homo in Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae. From left to right: Troglodyta bontii, or Homo troglodytes, in Linnaeus; Lucifer aldrovandii, or Homo caudatus; Satyrus tulpii, a chimpanzee; and Pygmaeus edwardi, an orangutan.

In this brief historical sketch we can see the main themes of human evolution and its controversies, and what is perhaps striking is the extent to which the issues that form the primary subject matter of this book were present not only among the founding fathers of evolutionary biology, but even prior to that. In both the Great Chain of Being and evolutionary trees we have the strong idea that nature can be seen as a continuity of form, on which humans can be placed. Among both natural philosophers and evolutionary biologists there is the problem of how to find a place within these schemes for humans that can reflect both their unique abilities and their evolutionary heritage. And finally, there is the idea of change, or progress to some, whereby something that was not present at one stage of evolution, or history, does emerge, and comes to thrive.

Humans, race, and progress

FIGURE 1.5 Racism in anthropology: In the early decades of the twentieth century, racism was an implicit part of anthropology, with “white” races considered to be superior to “black” races, through greater effort and struggle in the evolutionary race. Here, the supposed ascendancy of the “white” races is shown explicitly, in Earnest Hooton’s Up from the Ape, second edition, 1946.

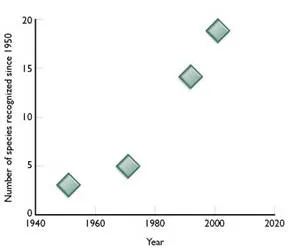

Modern paleoanthropology, the study of human evolution, has amassed a huge amount of evidence to help solve these problems (Fig. 1.6), and has available to it methods entirely undreamt of by the Victorians, but nonetheless it is worth remembering that it was within four years of the publication of The Origin of Species that Thomas Huxley had put his finger on the central problem of human evolution – namely our place in nature, or how we can both “mind the gap” and still remain faithful to evolutionary biology. As we shall see, archeology, fossils, and genetics have all provided ways of filling the gap between humans and the apes, which Huxley had thought unbridgeable. The science of paleoanthropology has emerged to fill the gap. In particular, it can set out to answer two major questions: first, whether the differences between humans and other animals are ones of degree or ones of kind, and second, the extent to which humans are not only unique in the sense that they are different as any species might be, but also uniquely different in the way they have acquired their basic characteristics.12

That these questions remain to be answered can be illustrated with reference to two biologists’ thoughts on the subject of the gap. At one extreme is Julian Huxley, grandson of Thomas Henry, who suggested that humankind’s special intellectual and social qualities were such that they should be recognized formally by assigning Homo sapiens to a new grade, the Psychozoan. “The new grade is of very large extent, at least equal in magnitude to all the rest of the animal Kingdom, though I prefer to regard it as covering an entirely new sector of the evolutionary process, the psychosocial, as against the entire non-human biological sector.”13 At the other end lies Jared Diamond, who argued on the basis of genetic evidence that humans should actually be placed in the same category as chimpanzees, and that we are in fact nothing more than the “third chimpanzee.”14 The power of the study of human evolution is that the answers to these questions can now be treated empirically as well as philosophically.

FIGURE 1.6 The growth of the hominin fossil record: While changes in approach and perception have been important in the development of our understanding of human evolution, one of the most important factors has been the growth of the fossil record. When Darwin wrote The Origin of Species there were virtually no fossils known; now they number in their thousands. This graph shows changes in the number of hominin species recognized. (Courtesy of Robert Foley.)

ESTABLISHING THE LINK BETWEEN HUMANS AND APES: HISTORICAL VIEWS

Debate over human origins has advanced substantially in recent years, particularly in broadening the scientific basis of the discussions. Nevertheless, many of the issues addressed in current research have deep historical roots. A brief sketch of the subject’s progress during the past 100 years or so will put modern debates into historical context.

KEY QUESTION How has the way scientists have perceived the relationship between humans and other animals changed over a century and a half of research and discovery?

Two principal themes have been recurrent in the last century of paleoanthropology (Fig. 1.7). First is the relationship between humans and apes: how close, how distant? Second is the “humanness” of our direct ancestors, the early hominins – do the characteristics of humanity go back to the very earliest hominins and beyond, or are they a recent acquisition? (“Hominin” is the term now generally used to describe species in the human family, or clade; until recently, the term “hominid” was used, as discussed in chapter 8.)

FIGURE 1.7 Two themes in human evolutionary research: Two questions have d...