![]()

Chapter 1

The plant cell

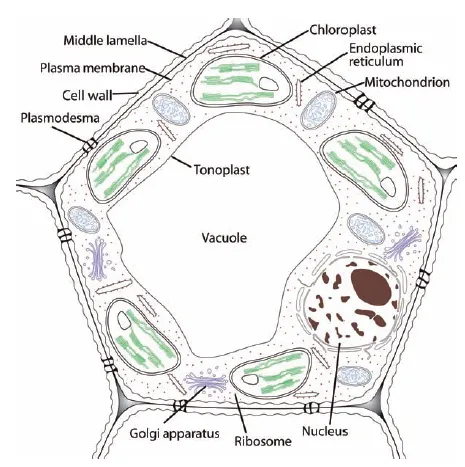

We appreciate plants for their beauty and usefulness, and on a different level, for the ability of plant species to adapt to an amazing diversity of climates and soils (two of many abiotic influences) as well as their ability to interact with microbes, animals, and other plants (biotic influences). The differences in characteristics such as stem, leaf, and flower structure that result from these and other adaptations were the original basis for classification of plants into different taxonomic groups. However, for all their differences in overall appearance (morphology), plants have the same basic structures at the cellular level, so we begin by looking at the cellular structures of plants. Figure 1.1 is a simplified illustration of a plant cell, and the structures labeled in Figure 1.1 are discussed in more detail in this and other chapters.

Protoplast

The protoplast is a collective term that includes the plasma membrane and the cellular objects it contains. It is filled with liquid, the cytosol, that bathes the cellular organelles including the nucleus. The protoplast includes all the “living” parts of the cell, so the cell wall to its outside is not included. The protoplast is composed of 60–75% proteins by dry weight.

Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is the protoplast minus the nucleus. The nucleus directs the work that goes on in the cytoplasm.

Cytosol

The cytosol is the liquid portion (matrix) of the cytoplasm, which surrounds organelles and in which a number of proteins, salts (including nutrient ions), and sugars are dissolved. The cytosol has the thickened consistency of a gel. The cytosol of adjacent cells is continuous, by way of plasmodesmata.

Cell walls

The plant cell protoplast is enclosed by a fibrous wall that grows as the cell expands to its mature size, but which becomes cross-linked and eventually limits the growth of the cell, defining and supporting the cell and collectively providing support for stems and leaves. Some cells, like photosynthetic and storage cells, only have a thin primary cell wall, and other cells have both a primary wall and a thick, lignified and therefore rigid secondary cell wall, either to retain the cell’s shape against the tension of water movement through the plant, as in xylem cells, or to provide concentrated regions of support or protection as in fiber cells or sclerids. The trunk of a tree is made up of concentric layers of water-transporting (xylem) cells with secondary walls that serve both water-carrying and support functions.

Components of the cell wall

Cellulose

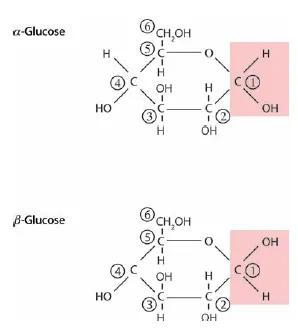

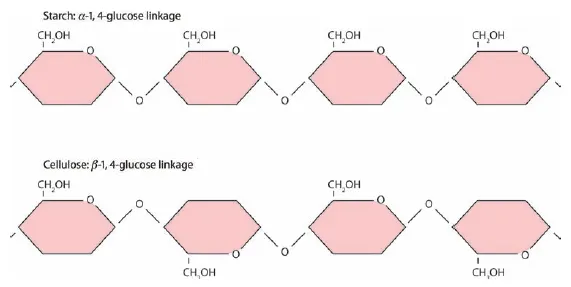

The fundamental component of cell walls is cellulose, which in turn is made up of long chains of glucose molecules, from thousands to tens of thousands of glucose units per molecule of cellulose. The chemical structure of glucose is illustrated in Figure 1.2, with each of the six carbon atoms (C) numbered. α- and β-Glucose differ in the orientation of the bonds at C-1. Starch and cellulose are both long chains of glucose, but starch is easily digested by monogastrics, like humans, while the bonds between glucose molecules in cellulose are most commonly broken by enzymes produced by microbes inhabiting the guts of ruminants, such as cattle and sheep (and termites). The difference in these chains of glucose is illustrated in Figure 1.3. Bonds in both starch and cellulose are between the 1- and 4-carbons of successive glucose molecules, but while in starch the orientation of each α-glucose molecule in the chain is the same, in cellulose every other β-glucose molecule is flipped on its horizontal axis.

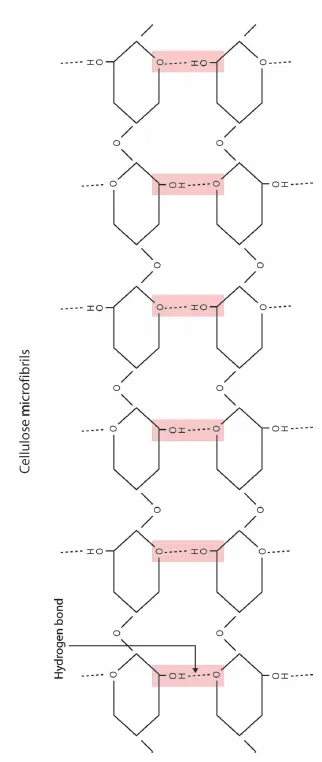

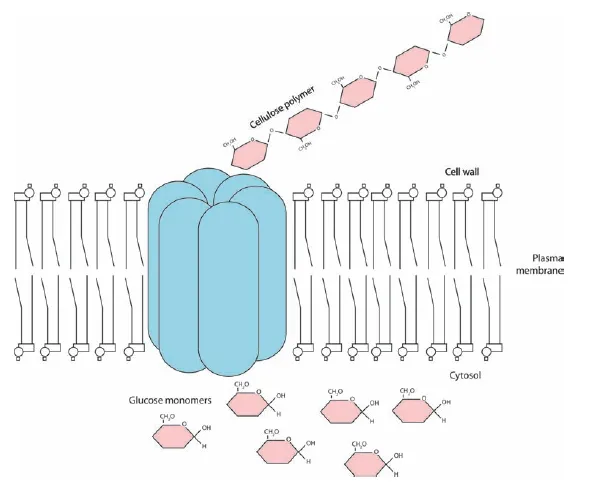

Cellulose is the “fiber” in paper. Cellulose molecules are grouped together into microfibrils consisting of 50–60 cellulose molecules held together by hydrogen bonds, which are relatively loose bonds but effective in large numbers, as in cellulose (Figure 1.4). Cellulose is such a big molecule that it is synthesized at the plasma membrane rather than inside the protoplasm. Microfibrils are extruded into the extracellular matrix, like toothpaste from a tube (Figure 1.5). Other cell wall components are secreted into the cell wall by way of Golgi vesicles, and assemble around the cellulose microfibrils.

Hemicellulose

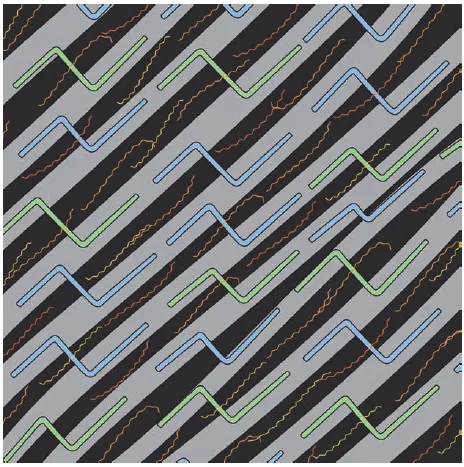

Hemicellulose also consists of chains of sugars, but the sugars are much more diverse than in cellulose, which contains only glucose. Hemicelluloses are highly branched because of the bonds that form among the sugars that make them up, and they form a network that coats the much larger cellulose microfibrils. Hemicelluloses adhere to cellulose by way of hydrogen bonds. Hemicellulose molecules coating individual cellulose microfibrils become cross-linked or bound together by covalent bonds, which limits cell wall expansion because the cellulose microfibrils can no longer slide past each other and allow the cell wall to grow. In Figure 1.6, the components of the cell wall are illustrated to show hemicelluloses forming cross-linkages between cellulose microfibrils.

Pectin

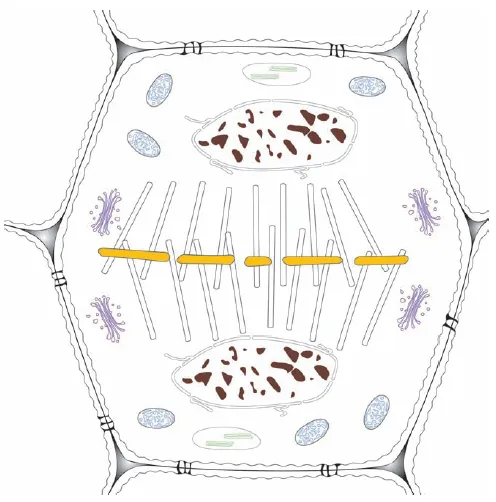

The middle lamella is the outermost layer of a plant cell and has a high concentration of pectins, which consist of uronic acids, the acidic (and therefore charged) forms of glucose and galactose, and other sugars. The middle lamella is the first boundary formed between what will become adjacent cells during cell division. In cell division, the genetic material of the cell is duplicated and the two groups of chromosomes move to opposite ends of the cell. In Figure 1.7, the middle lamella (yellow) is beginning to form as the boundary between the two new cells. The phragmoplast, a remnant of the organizing structure needed to divide the genetic material, which is shown as groups of white cylinders, is oriented between the daughter nuclei and the developing middle lamella.

After cell division, the primary cell wall forms to the inside of the middle lamella, and also has a relatively high content of pectin (up to 35%). The secondary cell wall, when present, then forms to the inside of the primary cell wall. The components of both walls are formed in the protoplast and secreted via the Golgi apparatus across the plasma membrane.

Extensin

A structural protein (in contrast to enzymes, which are soluble in the cytoplasm or the matrices of the cellular organelles), extensin, forms a network within the cell wall that can become cross-linked, like the hemicellulose network. Extensins make up, at most, about 10% of the cell wall, and were first identified in broadleaf plants (dicots), but proteins with similar functions are found in the grasses (monocots).

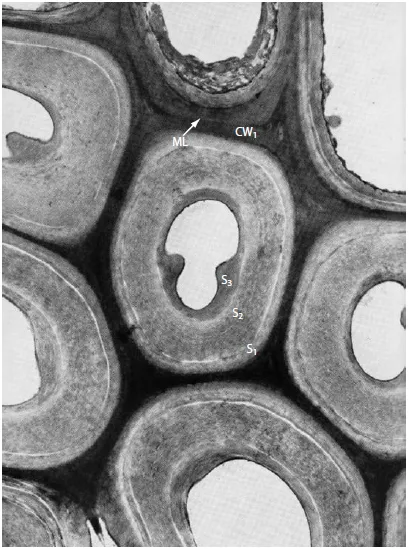

Secondary cell walls

In structural cells like fibers and in the water-carrying xylem cells, additional cell wall layers are laid down inside the primary cell wall after cell growth stops. These secondary cell walls have a higher cellulose content than primary walls, and may be distinctly layered. In Figure 1.8, which is an electron micrograph of fiber cells, the middle lamella (ML), primary cell wall (CW1), and distinct layers of the secondary cell wall (S1, S2, and S3) can be seen. The walls of these cells also become lignified, a process in which small lignin precursor molecules are secreted into the cell wall and assemble into large, unorganized molecules that displace water (see Chapter 14). The function of lignin is to waterproof xylem vessels and to make cell walls resistant to degradation by invading pathogens. Lignin also greatly increases the rigidity of the cell wall, and is therefore an important component of wood. However, lignin must be extracted for the production of paper, and greatly reduces the digestibility of the fiber cells in plants such as the grasses used as animal feed. Xylem cells, which are the water-carrying cells in roots and shoots, and fiber cells do not contain a protoplasm at maturity and therefore are nonliving cells.

Plasma membrane/cytoplasmic membrane/plasmalemma

The plasma membrane, cytoplasmic membrane, and plasmalemma are all accepted names for the selectively permeable membrane that encloses the living contents of the cell and controls the movement of materials into and out of the cell.

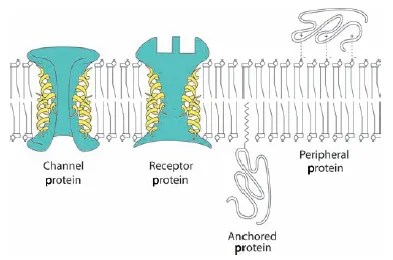

Membranes

Plant cell membranes are primarily made of lipids (fats and oils) and proteins. Membranes are usually described as consisting of a lipid bilayer because of the way the lipid molecules are arranged, but many proteins are embedded in this bilayer (Figure 1.9). In many cases, these proteins act as gateways for regulation of the contents of the cell.

Membrane lipids

The dominant lipids in the plasma membrane are phospholipids, which have a central glycerol molecule with a phosphate molecule attached at one end (the “head”) which is water-loving (hydrophilic) and a water-fearing (hydrophobic) “tail” composed of two fatty acids (making these phospholipids diglycerides). The fatty acids are partly unsaturated, making the lipid bilayer fluid, like oils (see Chapter 9).

Phospholipids spontaneously self-assemble into a bilayer in aqueous solutions like a plant cell. They turn their hydrophilic heads outward, some toward the cell wall that encloses the plasma membrane, and some toward the aqueous cell protoplasm, and turn their hydrophobic tails inward to form a double layer. Membranes are fluid—the molecules they contain can easily move past each other in the membrane—but they are also very stable. Membranes can exclude most charged molecules, like nutrient ions, which allows them to control movement of these nutrients into and out of the cell. Water and the gases oxygen and carbon dioxide, however, can cross the lipid bilayer relatively easily.

Other membranes, especially the internal membranes of the chloroplast, contain a large amount of glycolipids, where the head group contains one or two molecules of the sugar galactose instead of a phosphate, and sulfolipids, with a sulfate instead of a phosphate as part of the head group. In these cases, as for phospholipids, the heads are hydrophilic.

Membrane proteins

Proteins make up as much as 50% of the mass of cell membranes. The amino acid composition of proteins determines how the protein is incorporated into the lipid bilayer. If the protein spans the membrane from inside to out, it is an integral protei...