- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this ground-breaking new book on the Norteña and Sureña (North/South) youth gang dynamic, cultural anthropologist and linguist Norma Mendoza-Denton looks at the daily lives of young Latinas and their innovative use of speech, bodily practices, and symbolic exchanges that signal their gang affiliations and ideologies. Her engrossing ethnographic and sociolinguistic study reveals the connection of language behavior and other symbolic practices among Latina gang girls in California, and their connections to larger social processes of nationalism, racial/ethnic consciousness, and gender identity.

- An engrossing account of the Norte and Sur girl gangs - the largest Latino gangs in California

- Traces how elements of speech, bodily practices, and symbolic exchanges are used to signal social affiliation and come together to form youth gang styles

- Explores the relationship between language and the body: one of the most striking aspects of the tattoos, make-up, and clothing of the gang members

- Unlike other studies – which focus on violence, fighting and drugs – Mendoza-Denton delves into the commonly-overlooked cultural and linguistic aspects of youth gangs

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Homegirls by Norma Mendoza-Denton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

LA MIGRA

“M-I-I-G-R-A-A-A-A-a-a-a!” A fast-decaying echo followed the scream. It was the kind of echo where you can hear the sound waves buzzing in your ear.

Feet scurried all around; creeping under bushes, jumping over rocks, then frozen in mid-step behind cocked-open dumpsters. Hoping that the Border Patrol agent would pass them by, the immigrants held their breath, shoulders tense and armpits hollowed. The agent brushed aside weeds and grasses with her foot, counting backward quietly to herself. Leaves rustled, and a soft in-breath drew her eyes through a thicket and met them in a sustained gaze. Sergio knew it was over. He looked down and emerged defeated without a word. One by one the immigrants were found until only one remained. Time was running out. A bell’s vibrato finally clamored.

“OK, fine, I give up!” huffed Laura, the designated border patrol agent. Yadzmin, the smallest of the “immigrants,” only thirteen, had slipped between a candy machine and the wall. She came out yelling “I WO-ON! I get to be the Border Patrol tomorrow! Lero-lero, candilero! And YOU all have to be the immigrants and I’m going to get all of you! Nyah-nyah, nyah-nyah!” A twist of her hip marked victory and the end of recess as she skipped toward PE class.

Children’s games often go unnoticed. I knew that as I watched them play that day. Only later do we reflect on them as diagnosis and prophecy: ring-around-the-rosie acted out the plague that killed more than a third of medieval Europe.1 This time a playful cops-and-robbers chase, which the children called “migra-tag,” sprang alongside the referendum polls in California that year. Proposition 187, also known as “Save Our State” or SOS, had been introduced by then-Governor Pete Wilson in the summer of 1995, and rumors swirled around the immigrant communities for months. Although everyone talked about what the impact of the proposition might be, somehow we under-estimated it, thinking that it was a fringe conservative movement. We thought it would never pass. Proposition 187 sought (and eventually passed and resulted in) the denial of social services to undocumented immigrants; public education and Medicaid were the main targets of the proposition. Other less expensive social benefits were also casually included, like an afterthought: well-baby (prenatal and postnatal) care, emergency room visits, and school lunches. Proposition 187 passed in November of 1995, approximately one year after the beginning of this project. Any undocumented immigrants that were caught using social services could be summarily deported. That included a large proportion of the Latina and Latino students at Sor Juana High School (SJHS).

On the way to gym class Yadzmin found Lucia, Tanya, and Cristina, las niñas Fresas (lit. “strawberry girls”: a Mexican Spanish slang term for a young person from the urban, middle-class, predominantly European-descent elite), and stopped to talk to them. They were getting ready for dance class, stretching on the wooden dance floor in their black leotards and tights. Mr Jones the dance teacher walked by on his way to the lockers. When he saw the girls he sang ridiculously, “Chiqui-ta Ba-na-na.” The girls looked up with quizzical expressions and parroted back, “Chiquita Ba-NA-na!”

“¿Qué onda? (What’s with him?)” Lucia wanted to know.

“¿Quién sabe? (Who knows?) I have no idea why he always says that to us,” said Tanya.

There was no way that the recently-arrived immigrant girls could ever have heard the commercial jingle that now looped in the back of my head. The ditty was introduced in 1945, when United Fruit Company unloaded its last military cargo and sent its fleet of ships to the Caribbean to harvest bananas. Chiquita Banana was a mass-marketing campaign aimed at entertaining war-weary Americans and familiarizing them with a new fruit from the Caribbean. Who would have thought bananas would become ubiquitous? At its peak, the song was played over 350 times a day on the radio, and Miss Chiquita, the ripe banana made flesh, was such a celebrity that UFC changed its name to Chiquita Brands. Around the same time, Carmen Miranda became not only the archetypal Latin sexpot but the highest-paid woman in the US at the time, linking Latinas, bananas, and big business.

Figure 1.1 Carmen Miranda: The South American Way.

... Hell-o A-mi-gos!

I’m Chiquita Banana and I’ve come to say

Bananas have to ripen in a certain way

When they are fleck’d with brown and have a golden hue

Bananas taste the best and are the best for you!

[ … ]

But, bananas like the climate of the very, very tropical equator

So you should never put bananas in the refrigerator!

Music © 1945 Shawnee Press Inc.

There were other variations of the song, with the main character shown in commercials first as an animated banana, emerging like a Botticelli Venus from the peel, and eventually personified by a long line of Latina women (and one Italian-American) with Miranda-esque ripe fruit head-dresses and Brazilian-Bahiana outfits.2 The South American bombshell swept the country!

I’m Chiquita Banana and I’ve come to say

To a fellow’s heart the stomach is the way

It’s an ancient formula you must admit,

And we’ll put it to the test with a banana split!

There’s some ice cream in the freezer

That was purchased yesterday,

These bananas that I’m holding

are so flecked and ripe and golden...

“Oh I think I see a beauty,”

“She’s a honey,”

“How’d we miss her?!”

“And her banana splits are something

that makes me want to kiss her.”

“Norma, what does that mean, when he says Chiquita Banana?” the girls insisted. “I don’t know,” I lied. I was hoping that the angry flush spreading forward from my ears would not give me away.

At the time, I thought I knew. But to tell the truth, now I’m not quite sure why Mr Jones said that. Maybe it was just a fleeting moment captured on tape. A female schoolteacher from Texas who heard my recording of the incident claimed the moment was too small, too fleeting to make a big deal. Another friend, a Spanish immigrant to England, had a gut reaction: totally offensive. It reminded him of when he was a kid and the English children taunted him, yelling “Spanish Onion!” when he walked by. He could never figure it out, and for years he kept asking himself, onions: WHY onions? Twenty minutes after recounting this he came back and told me that he thought the Chiquita Banana comment was ambiguous. Maybe the teacher had no other way to relate. He didn’t speak Spanish, after all. Maybe he understood Chiquita to be a diminutive, endearing somehow. There was just no way to know. Which is just as well because I didn’t say anything at the time.

The Meaning of Dancing: Banda and Rock En Español as Class Codes

A few weeks after this incident Lucía and Tanya invited me to a Fresa party, held on a Saturday afternoon in a spacious rented party room at the Fox and Hound apartments. It was Tanya’s fourteenth birthday, and half the teenage boys were sullenly playing cards and munching on pretzels, while the rest were nuzzling their girlfriends into the corners of the party room, done up in shades of forest green and maroon. I had brought some chocolate-chip cookies that my boyfriend Rob had baked – Jose and Domingo, the basketball-obsessed twins from Guadalajara, said “¡Esos Gringos! (Those Americans!)” and laughed: I think they were amused at the thought that my American boyfriend not only lived with me – in subtle ways I found out they disapproved of this – but even took orders to bake cookies. Tanya’s mom had made a big chocolate cake. The girls at the party brought fruit salad and other small snack foods, and sodas. There was no alcohol, and at some point we played musical chairs. Pretty sedate really for my idea of a teenage party, and nothing like the blowout Alice in Wonderland drug-themed parties the wealthy Sor Juana High School jocks flippantly described and ranked in the school newspaper.

Tanya had dressed up as the rockera she aspired to be, with her curly brown hair down to the middle of her back; jeans, a white t-shirt, a belt with little silver spikes, and a black jeans vest. She was DJ on a boombox someone had brought (yes, back in the 1990s there were still boomboxes), and she was playing Rock en Español, but accepting requests for techno and a little bit of house music. Rancheras (Mexican country music), banda (polkas), and especially cumbias with their tropical rhythms were totally out of the question. In a later interview, Tanya explained:

| TANYA: | No es por insultar a nadie ¿no? bueno porque se sientan mal o algo así pero, o sea, yo la verdad, Banda solamente una vez escuché en una película [risa]. Y era una película de un pueblito, ¿ves? O sea, uno que es de ciudad, pus, no va allá en algo de, de un pueblito, no? No sé si te has dado cuenta que los únicos que bailan Banda son los de los barrios. Ahí de, de donde yo vivía, pus no se acostumbraba eso ¿ves? A mí me gusta Rock en Español, así Tecno, y no sé, o sea, tú sabes no, como que un estilo más americano aunque sea en español. |

| TANYA: | I don’t mean for this to insult anyone OK? Like to make anyone feel bad, but the truth is that Banda, I only heard it once before, and it was in a movie [laughter]. And it was a movie about a little town. I mean, when you are from the city, you just aren’t going to go for things from a little town. I don’t know whether you’ve noticed that the only ones who dance Banda are the ones from the barrios. Where I lived, we were just not used to that. I like Rock en Español, Techno, you know, a style that is more American although it is in Spanish. |

Despite Tanya’s insistence that Banda songs not be played at the party, I knew Güera liked Banda. Güera was from the high plains of Michoacán, a rural area of central-west Mexico where young people were not swept up in Americanized rock music. I listened to Banda when riding in Güera’s car; she’d brake to the rhythm of it while I watched the pavement go by at my feet where the passenger side floorboard should have been. And she could dance Banda too, her long hair sweeping the floor as she hung backward, supported by her partner’s arm in athletic dips. I had seen Güera dancing once with Junior, back when they were boyfriend and girlfriend and still spoke to each other.

I think Güera and Junior broke up partly because of the Piporro divide. Güera was a Piporra, a girl from the countryside whose family back in Mexico worked on a ranch. Tanya, a middle-class Fresa from the big city of Puebla, clearly looked down on anything from the Mexican countryside merely because it was rural and un-modern. Junior was not a Fresa, he was from a working-class background, but like Tanya he was from an urban area and similarly derided Piporros. In addition, Junior had gone and joined the Sureño gang, which claimed allegiance to the much more abstract “South,” leaving very little room for the exploration of other communities. I think the low-grade annoyance of Piporro put-downs eventually got on Güera’s nerves, straining relations with both Junior and Tanya.

Some time after the Güera/Junior breakup, I interviewed Junior and he expanded on Tanya’s association of Banda music with rurality, linking it directly to the Piporros.

| JUNIOR: | Banda es música de Piporro. Me gustará bailarla pero por orgullo no la escucho. Banda is the music of Piporros. I might like to dance it but out of pride I don’t listen to it. |

| NORMA: | ¿Por orgullo de qué? Pride of what? |

| JUNIOR: | De que no seas Piporro. Of not being a Piporro. |

| NORMA: | ¿Qué quiere decir Piporro? What does that mean, Piporro? |

| JUNIOR: | Un Piporro es una persona de rancho, bajado del monte, que oye tamborazos. ¡Un indio! ¡Que se dedica a crecer vacas, chivos! A Piporro is a person who is from a ranch, who’s come down from the hills, who listens to big-drum music (Banda). An indio! Who raises cows and goats for a living! |

“Güera” means blonde in Spanish, and this was unusual for a Piporra; as Junior mentioned, prototypical Piporros are thought to be of indigenous extraction. Güera was unusual in another way: she spoke totally fluent English from being a circular migrant, though she was still somehow placed in English as a Second Language (ESL) classes. When I first met her, I thought she might be from Russia, another common point of origin for young people in the ESL classes. She had wavy, very long white-blond hair, with sprayed-stiff “clam shell” bangs. For the party at the Fox and Hound apartments she had replaced her blue bandanna ponytail holder with a black satin ribbon, and the ponytail sprouted as usual from the top of her head. She wore a black satin shirt tucked into green jeans with black high-top sneakers. No blue today, no gang colors. I guessed she was trying to fit in with the Fresas. Tanya the would-be Rockera Fresa could be very disapproving of Güera’s clothes, of her music, and especially of her boyfriends. She had hated Junior.

What Would You Do If Your Boyfriend Was Into Gangs?

At the party Güera told me that her new boyfriend Alejandro was in jail. She spoke to me in Mexican Rural Spanish code-mixed with English.

“Why is he in jail?” I asked her.

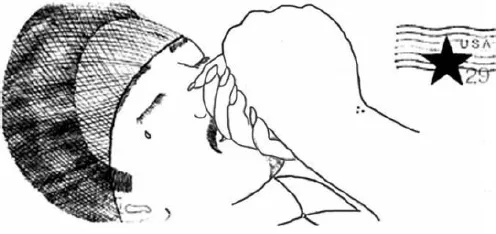

“He got in a fight with this guy, but that’s not why he is in jail; the cops thought he was trying to steal something but he was only trying to get in a fight with some fool that insulted him.” She caught her breath. “No fue su culpa. (So it wasn’t his fault.) Anyway he’s in jail, he’s been there two months and has three to go but he sent me a Valentine’s Day card. Look.”

Güera produced an envelope that had a reluctant bit of white space left on it, just enough to write her address. The rest of the envelope was given to an elaborate drawing, where a man with a hairnet and a tear tattooed on his cheek kissed the disembodied hand of a woman, chivalrously, Cinderella-style. He seemed to be floating in the kiss, eyes closed, and on the corner of his wrist there was another little tattoo. The three triangular dots meant he was a Sureño. Inside there was a card with a poem, Las flores son bellas pero frágiles, y así son las mujeres: bellas, frágiles, y necesitan alguien quien las cuide (Flowers are beautiful but they’re fragile, and that is how women are: beautiful, fragile, and needing someone to take care of them). This seemed pretty ironic to me since Alejandro was in jail and not in a great position to take care of anyone.

Figure 1.2 Valentine’s Day Envelope from Alejandro to Güera.

After showing me the envelope Güera wanted to know, “Do you like Norteños?” I hesitated and wondered who this might get back to, but she didn’t wait to hear my answer. I think she wanted to get things off her chest. “I really hate Norteños because they broke the windows of my father’s car. It was the only car he had. They wanted it and he wouldn’t give it to them, so instead of taking it they just ruined it. Ever since then, I’ve hated Norteños,” she said. And after a pause, “What would you do if your boyfriend was – into gangs, you know, what would you do?”

It was hard to imagine new-age, vegetarian Rob in any kind of gang, though he had been in an Ashram in India.

“Just imagine that he was in a gang, do you think he could change? Just hypothetically?”

“Ay, Güera. I don’t know. It’s important to be loyal, but you can’t get sucked into a remolino (vortex), you have to be your own person and watch out for yourself.”

“Do you think I can change Alejandro? Tanya says that if he really loved me he could change for me. He would stay out of gangs, totally leave the Sureños if I told him to.”

I wanted to tell her that I thought you can’t really change people but we got interrupted. Just then, Karina walked by and having heard the last of our exchange, said no, forget it. No cambian (They don’t change). Someone else who was overhearing said anyone could change if they really tried. Tanya walked by and rolled her brown eyes in condemnation.

According to Güera, when Tanya first came to Fog City she too was friendly with all the Sureños. How could she not be? When she arrived from Mexico Tanya shared the same beginning ESL classes with them; they were the first people who included her, who said hello to her every day, and practically the only people that she could understand at first because of their resolute Spanish use. The Sureño boys accepted her as a “border sister,” invited her to hang out by the parking lot behind the Target on Industrial Way, and played Oldies for her. Being in no position to refuse friendship, Tanya went along, listening to Angel Baby and other American songs from the 1960s that she thought were incredibly old-fashioned. But Tanya didn’t really like the Sureños; she could tell by their accents and their mannerisms that they had been poor in Mexico, even if now her Mom had to work alongside their parents. Most of the Sureños were from the depopulated regions of the Mexican central-western states,3 whose melancholy names were now borne by mom-and-pop restaurants in their new California neighbor-hoods: La Jaliscience. La Michoacana. La Oaxaqueña.4

Lock-Down Piporras and Cosmopolitan Fresas

Tanya looked around for some other social options outside the ESL classes. She joined the Ballet Folklórico, the Mexican folkloric dance group where Ms Carla, a bilingual Mexican-American teacher, was more interested in nurturing a small group of what Robert Smith5 has perceptively called “lock-down girls.” As the most recent of immigrants from rural Mexico, Piporras were the girls that other Latinas in the school sometimes complimented, sometimes taunted as being “traditional Mexican girls.”

Tanya, a Fresa urbanite who had already been to raves with her cousins in Mexico, was a lot wilder than your average Piporra, and didn’t get along with Ms Carla. Tanya found the Piporra group and its constant supervision too constraining, and when she finally met the other Fresas, she abruptly stopped speaking to all the Sureños in her class, and buried her nose in her books just to get out of there as quickly as possible. Soon enough Tanya was promoted out of the beginning ESL class and that is when her Fresa career really took off.

Güera, on the other hand, was still friends with all the Piporras who had been her network before she started hanging around with Junior. At Sor Juana High School, it was the locked-down Piporras who were considered “at risk,” the target population of specialized school programs like Migrant Education,6 a federally-funded program that provided academic assistance to youth whose parents’ farm work resulted in long periods of school absences.

Piporras’ daily rou...

Table of contents

- COVER

- CONTENTS

- SERIES PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- DEDICATION

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF SOURCES

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1: LA MIGRA

- CHAPTER 2: BEGINNING FIELDWORK

- CHAPTER 3: NORTE AND SUR: GOVERNMENT, SCHOOL, AND RESEARCH PERSPECTIVES

- CHAPTER 4: HEMISPHERIC LOCALISM: LANGUAGE, RACIALIZED NATIONALISM, AND THE POLITICIZATION OF YOUTH

- CHAPTER 5: “MUY MACHA”: GENDERED PERFORMANCES AND THE AVOIDANCE OF SOCIAL INJURY

- CHAPTER 6: SMILE NOW CRY LATER: MEMORIALIZING PRACTICES LINKING LANGUAGE, MATERIALITY, AND EMBODIMENT

- CHAPTER 7: ICONS AND EXEMPLARS: ETHNOGRAPHIC APPROACHES IN VARIATIONIST SOCIOLINGUISTICS

- CHAPTER 8: VARIATION IN A COMMUNITY OF PRACTICE

- CHAPTER 9: “THAT’S THE WHOLE THING [tiη]!”: DISCOURSE MARKERS AND TEENAGE SPEECH

- CHAPTER 10: CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- APPENDIX

- INDEX