![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to evidence-based infectious diseases

Mark Loeb, Marek Smieja & Fiona Smaill

Our purpose in this chapter is to provide a brief overview of evidence-based infectious diseases practice and to set the context for the chapters which follow. We highlight evidence-based guidelines for assessing diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, and discuss the application of evidence-based practice to infectious diseases, as well as identifying areas in which such application must be made with caution.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Evidence-based medicine was born in the writings of clinical epidemiologists at McMaster University, Yale, and elsewhere. Two series of guidelines for assessing the clinical literature articulated these, then revolutionary, ideas and found a wide audience of students, academics, and practitioners alike [1, 2]. These guidelines emphasized the randomized clinical trial (RCT) for assessing treatment, now a standard requirement for the licensing of new drugs or other therapies. David Sackett, the founding chair of the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at McMaster University, defined evidence-based medicine as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of patients” [3].

These guidelines, which we summarize later in the chapter, were developed primarily to help medical students and practicing doctors find answers to clinical problems. The reader was guided in assessing the published literature in response to a given clinical scenario, to find relevant clinical articles, to assess the validity and understand the results of the identified papers, and to improve their clinical practice. Aided by computers, massive databases, and powerful search engines, these guidelines and the evidence-based movement empowered a new generation of practitioners and have had a profound impact on how studies are conducted, reported, and summarized. The massive proliferation of randomized clinical trials, the increasing numbers of systematic reviews and evidence-based guidelines, and the emphasis on appropriate methods of assessing diagnosis and prognosis, have affected how we practice medicine.

Evidence-based infectious diseases

The field of infectious diseases, or more accurately the importance of illness due to infections, played a major role in the development of epidemiological research in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Classical observational epidemiology was derived from studies of epidemics – infectious diseases such as cholera, smallpox, and tuberculosis. Classical epidemiology was nevertheless action-oriented. For example, John Snow’s observations regarding cholera led to his removal of the Broad Street pump handle in an attempt to reduce the incidence of cholera. Pasteur, on developing an animal vaccine for anthrax, vaccinated a number of animals with members of the media in attendance [4]. When unvaccinated animals subsequently died, while vaccinated animals did not, the results were immediately reported throughout Europe’s newspapers.

In the era of clinical epidemiology, it is notable that the first true randomized controlled trial is widely attributed to Sir Austin Bradford Hill’s 1947 study of streptomycin for tuberculosis [5]. In subsequent years, and long before the “large simple trial” was rediscovered by the cardiology community, large-scale trials were carried out for polio prevention, and tuberculosis prevention and treatment.

Having led the developments in both classical and clinical epidemiology, is current infectious diseases practice evidence-based? We believe the answer is “somewhat”. We have excellent evidence for the efficacy and side effects of many modern vaccines, while the acceptance of before-and-after data to prove the efficacy of antibiotics for treating bacterial meningitis is ethically appropriate. In the field of HIV medicine we have very strong data to support our methods of diagnosis, assessing prognosis and treatment, as well as very persuasive evidence supporting causation. However, in treating many common infectious syndromes – from sinusitis and cellulitis to pneumonia – we have many very basic diagnostic and therapeutic questions that have not been optimally answered. How do we reliably diagnose pneumonia? Which antibiotic is most effective and cost-effective? Can we improve on the impaired quality of life that often follows such infections as pneumonia?

While virtually any patient presenting with a myocardial infarction will benefit from aspirin and thrombolytic therapy, there may not be a single “best” antibiotic for pneumonia. Much of the “evidence” that guides therapy in the infectious diseases, particularly for bacterial diseases, may not be clinical, but exists in the form of a sound biologic rationale, the activity of the antimicrobial against the offending pathogen, and the penetration at the site of infection (pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics). Still, despite having a sound biologic basis for choice of therapy, there are many situations where better randomized controlled trials need to be conducted and where clinically important outcomes, such as symptom improvement and health-related quality, are measured.

How, then, can we define “evidence-based infectious diseases” (EBID)? Paraphrasing David Sackett, EBID may be defined as “the explicit, judicious and conscientious use of current best evidence from infection diseases research in making decisions about the prevention and treatment of infection of individuals and populations”. It is an attempt to bridge the gap between research evidence and the clinical practice of infectious diseases. Such an “evidence-based approach” may include critically appraising evidence for the efficacy of a vaccine or a particular antimicrobial treatment regimen. However, it may also involve finding the best evidence to support (or refute) use of a diagnostic test to detect a potential pathogen. Additionally, EBID refers to the use of the best evidence to estimate prognosis of an infection or risk factors for the development of infection. EBID therefore represents the application of research findings to help answer a specific clinical question. In so doing, it is a form of knowledge transfer, from the researcher to the clinician. It is important to remember that use of research evidence is only one component of good clinical decision-making. Experience and clinical skills are essential components. EBID serves to inform the decision-making process. For the field of infectious diseases, a sound knowledge of antimicrobials and microbiologic principles are also needed.

Posing a clinical question and finding an answer

The first step in practicing EBID is posing a clinically driven and clinically relevant question. To answer a question about diagnosis, therapy, prognosis, or causation, one can begin by framing the question [2]. The question usually includes a brief description of the patients, the intervention, the comparison, and the outcome (a useful acronym is “PICO”). For example, if asking about the efficacy of antimicrobial-impregnated catheters in intensive care units [6], the question can be framed as follows: “In critically ill patients, does use of antibiotic-impregnated catheters reduce central line infections?” After framing the question, the second step is to search the literature. There are increasingly a number of options for finding the best evidence. The first step might be to assess evidence-based synopses such as Evidence-Based Medicine or ACP Journal Club (we admit to bias – two of the editors [ML, FS] are associate editors for these journals). These journals regularly report on high-quality studies that can impact practice. The essential components of the studies are abstracted and the papers are reviewed in an accompanying commentary by knowledgeable clinicians. However, since these journals are geared to a general internal medicine audience, many questions faced by clinicians practicing infectious diseases may not be addressed.

The next approach that we would recommend is to search for systematic reviews. Systematic reviews can be considered as concise summaries of the best available evidence that address sharply defined clinical questions [7]. Increasingly, the Cochrane Collaboration is publishing high-quality infectious diseases systematic reviews (http://www.cochranelibrary.com). Another source of systematic reviews is the DataBase of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb). To help find systematic reviews, MEDLINE can be searched using the systematic review clinical query option in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). If there are no synopses or systematic reviews that can answer the clinical question, the next step is search the literature itself by accessing MEDLINE through PUBMED. After finding the evidence the next step is to critically appraise it.

Evidence-based diagnosis

Let us consider the use of a rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcal infection in throat swabs. The first question to ask is whether there was a blinded comparison against an accepted reference standard. By blinded, we mean that the measurements with the new test were done without knowledge of the results of the reference standard.

Next, we would assess the results. Traditionally, we are interested in the sensitivity (proportion of reference-standard positives correctly identified as positive by the new test) and specificity (the proportion of reference-standard negatives correctly identified as negative by the new test).

Ideally, we would also like to have a measure of the precision of this estimate, such as a 95% confidence interval on the sensitivity and specificity, although such measures are rarely reported in the infectious diseases literature.

Note, however, that while the sensitivity and specificity may help a laboratory to choose the best test to offer for routine testing, they do not necessarily help the clinician. Thus, faced with a positive test with known 95% sensitivity and specificity, we cannot infer that our patient with a positive test for group A streptococcal infection has a 95% likelihood of being infected. For this, we need a positive predictive value, which is calculated as the percentage of true positives among all those who test positive. If the positive predictive value is 90%, then a positive test would suggest a 90% likelihood that the person is truly infected. Similarly, the negative predictive value is the percentage of true negatives among all those who test negative. Both positive and negative predictive value change with the underlying prevalence of the disease, hence such numbers cannot be generalized to other settings.

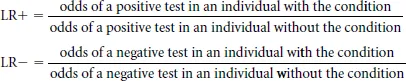

A more sophisticated way to summarize diagnostic accuracy, which combines the advantages of positive and negative predictive values while solving the problem of varying prevalence, is to quantify the results using likelihood ratios. Like sensitivity and specificity, likelihood ratios are a constant characteristic of a diagnostic test, and independent of prevalence. However, to estimate the probability of a disease using likelihood ratios, we additionally need to estimate the probability of the target condition (based on prevalence or clinical signs). Diagnostic tests then help us to shift our suspicion (pretest probability) about a condition depending on the result. Likelihood ratios tell us how much we should increase the probability of a condition for a positive test (positive likelihood ratio) or reduce the probability for a negative test (negative likelihood ratio). More formally, likelihood ratio positive (LR+) and negative (LR−) are defined as:

A positive likelihood ratio is also defined as follows: sensitivity/(1 – specificity). Let us assume, hypothetically, that the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test is 80% and the specificity 90%. The positive likelihood ratio for the antigen test is (0.8/0.1) or 8. This would mean that a patient with a positive antigen test would have 8 times the odds of being positive compared with a patient without group A streptococcal infection. The tricky part in using likelihood ratios is to convert the pretest probability (say 20% based on our expected prevalence among patients with pharyngitis in our clinic) to odds: these represent 1:4 odds. After multiplying by 8, we have odds of 8:4, or a 67% post-test probability of disease. Thus, our patient probably has group A streptococcus, and it would be reasonable to treat with antibiotics.

The negative likelihood ratio, defined as (1 – s ensitivity)/specificity, tells us how much we should reduce the probability for disease given a negative test. In this case, the negative likelihood ratio is 0.22, which can be interpreted as follows: a patient with pharyngitis and a negative antigen test would have their odds of disease multiplied by 0.22. In this case, a pretest probability of 20% (odds 1:4) would fall to an odds of 0.22 to 4, or about 5%, following a negative test. Nomograms have been published to aid in the calculation of post-test probabilities for various likelihood ratios [8].

Having found that the results of the diagnostic test appear favorable for both diagnosing or ruling out disease, we ask whether the results of a study can be generalized to the type of patients we would be seeing. We might also call this “external validity” of the study. Here we are asking the question: “Am I likely to get the same good results as in this study in my own patients?” This includes such factors as the severity and spectrum of patients studied versus those we will encounter in our own practice, and technical issues in how the test is performed outside the research setting.

To summarize, to assess a study of a new diagnostic test, we identify a study in which the new test is compared with an independent reference standard; we examine its sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios; and we determine whether the spectrum of patients and technical details of the test can be generalized to our own setting.

In applying these guidelines in infectious diseases, there are some important caveats.

- There may be no appropriate reference standard.

- The spectrum of illness may dramatically change the test characteristics, as may other co- interventions such as antibiotics.

For example, let us assume that we are interested in estimating the diagnostic accuracy of a new commercially available polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for the rapid detection of Neisseria meningitidis in spinal fluid. The reference standard of culture may not be completely sensitive. Therefore, use of an expanded reference (“gold”) standard might be used. For example, the reference standard may be growth of N. meningitidis from the spinal fluid, demonstration of an elevated white blood cell count in the spinal fluid along with gram-negative bacilli with typical morphology on Gram stain, or elevated white blood cell count along with isolation of N. meningitidis in the blood.

It is also important to know in what type of patients the test was evaluated, such as the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the spectrum of illness. Given that growth of microorganisms is usually progressive, test characteristics in infectious diseases can change depending when the tests are conducted. For example, PCR conducted in patients who are early in their course of meningitis may not be sensitive as compared to patients that presented with late-stage disease. This addresses the issue of spectrum in test evaluation.

Evidence-based treatment

The term “evidence-based medicine” has become largely synonymous with the dictum that only randomized, double-blinded clinical trials give reliable estimates of the true efficacy of a treatment. For the purposes of guidelines, “levels of evidence” have been proposed, with a hierarchy from large to small RCTs, prospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and case series. In newer iterations of these “levels of evidence”, a metaanalysis of RCTs (without statistical heterogeneity, indicating that the trials appear to be estimating the same treatment effect), are touted as the highest level of evidence for a therapy.

In general, clinical questions about therapy or prevention are best addressed through randomized controlled trials. In observational studies, since the choice of treatment may have been influenced by extraneous factors which influence prognosis (so-called “confounding factors”), statistical methods are used to “adjust” for identified potentially confounding variables. However, not all such factors are known or accurately measured. An RCT, if large enough, deals with such extraneous prognostic variables by equally apportioning them to the two or more study arms by randomization. Thus, both known and unknown confounders are distributed roughly evenly between the study arms.

For example, a randomized controlled trial would be the appropriate design to assess whether dexamethasone administered prior to antibiotics reduces mortality in adults who have bacterial meningitis [9]. We would evaluate the following characteristics of such a study: who was studied; was there true random assignment; were interventions and assessments blinded; what was the outcome; and can we generalize to our own patients?

When evaluating clinical trials it is important to ensure that assignment of treatment was truly randomized. Studies should describe exactly how the patients were randomized (e.g., random numbers table, computer generating). It is also important to assess whether allocation of the intervention was truly concealed. It is especially important here to distinguish allocation concealment from blinding. Allocation of an intervention can always be concealed even though blinding of investigators, participants or outcome assessors may be impossible. Consider an RCT of antibiotics versus surgery for appendicitis (improbable as this is). Blinding participants and investigators after patients have been randomized would be difficult (sham operations are not considered ethical). However, allocation concealment occurs before randomization. It is an attempt to prevent selection bias by making certain that the investigator has no idea to what arm (antibiotics versus surgery) the next patient enrolled will be randomized. In many trials this is done through a centralized randomized process whereby the study investigator is faxed the assignment after the patient has been enrolled. In some trials, the assignment is kept in envelopes. The problem with this is that, if the site investigator (or another clinician) has a preference for one particular intervention over another, the possibility for tampering exists. For example, if a surgeon who is a site investigator is convinced that the patient he has just enrolled would benefit most from surgery, the surgeon might be tempted to hold the envelope up to a strong light, determine the allocation, and then select another if the contents of the envelope do not indicate surgery as the allocation. This would lead to selection bias and distort the result of the clinical trial. This type of tampering has been documented [10].

The degree of blinding in a study should also be considered. It is important to recognize that blinding can occur at six levels: the investigators, the patients, the outcome assessors, adjudication committee, the data monitoring committee, the data analysts, and even the manuscript writers (although in practice few manuscripts are written blinded of the results) [11]. Describing a clinical trial as “double-blinded” is vague if in fact blinding can occur at so many different levels. It is better to describe who was blinded than using generic terms.

Similarity of groups at baseline should also be considered when evaluating randomized controlled trials to assess whether differences in prognostic factors at baseline may have had an impact on the result. A careful consideration of the intervention is also important. One can ask what actually constitutes the intervention – was there a co-intervention that really may have been the “active ingredient”?

Follow-up is another important issue. It is important to assess whether all participants who were actually randomized are accounted for in the results. A rule of thumb is that the potential for the results to be misleading occurs if fewer than 80% of individuals randomized are not accounted for at the end (i.e., loss to follow-up of over 20% of participants). More rigorous randomized controlled trials are analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. That is, all patients randomized are accounted for and are analyzed with respect to the group to which they were originally allocated. For example, an individual in our hypothetical appendicitis trial who was initially randomized to antibiotics but later received surgery would be considered in the analysis to have received antibiotics.

Having assured ourselves that the study is randomized, the randomization allocation was not prone to manipulation, and the randomized groups have ended up as comparable on major prognostic factors, we next examine the actual results. Consider a randomized controlled trial of two antibiotics A and B for community-acquired pneumonia. If the mortality rate with antibiotic A is 2% and that with B is 4%, the absolute risk reduction is the difference between the two rates (2%), the relative risk of A versus B is 0.5, and the relative risk reduction is 50%, that is the difference between the control and intervention rate (2%) divided by the control rate (4%). In studies with time-to-event data, the hazar...