![]()

Chapter 1

Process: Hot Workability 1

1.1. Introduction

The advantageous performance of duplex stainless steels in many applications, when compared with other stainless steels, is directly related to their austeno-ferritic microstructure [FLO 68, SOL 83, BER 91, COM 91, NIL 92A, NIL 92B]. However, the biggest difficulties in processing duplex stainless steels arise during hot working as a direct consequence of this same austeno-ferritic microstructure [IZA 07]. In general, duplex stainless steels have poor hot workability, which consequently leads to a relatively narrow processing window. This raises difficulties during their industrial processing and the severity of the problem often produces defects seen immediately in the hot rolled material or only detected in the finished product.

The different metallurgical factors behind the hot workability of duplex stainless steels are reviewed in this paper.

1.2. As-cast microstructure

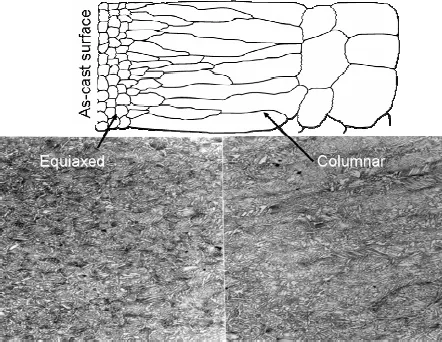

In general, duplex stainless steels of practical interest solidify to δ-ferrite, leading to the primary as-cast pattern shown schematically in Figure 1.1a in which a shell of small equiaxed grains in contact with the cast surface is followed by several millimeter long columnar grains and finally coarse equiaxed grains at the center of the cast.

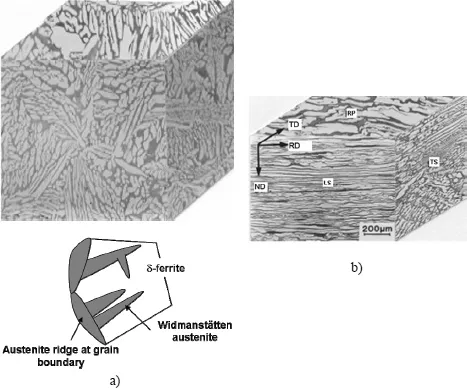

Duplex as-cast microstructures form during the cooling as a consequence of solid state precipitation of austenite ridges at δ prior grain boundaries and Widmanstätten microstructure inside the δ-ferrite grains, as seen in Figure 1.1b. The result is a distribution of plate-like austenite monocrystals oriented in space almost at random within a polycrystalline ferrite matrix, as seen in Figure 1.2a.

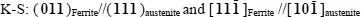

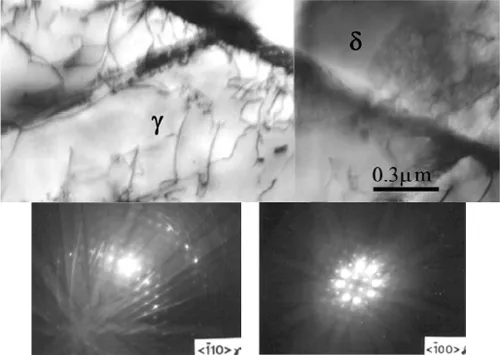

Widmanstätten austenite, like its homonymous ferrite, involves a combination of some diffusive and displacive transformations [OHM 95]. This kind of solid-state transformation imposes an orientation relationship of the type Kurdjumov-Sachs (K-S) or Nishiyama-Wasserman (N-W) between the new austenite and the parent ferrite [SOL 83, IZA 97A, IZA 98], as seen in Figure 1.3, lead to semi-coherent interphase boundaries [POR 92] due to lattice plane correspondences:

from which N-W can be generated by a rotation of 5.26° about [011]Ferrite.

The austenite ridges at ferrite grain boundaries maintain this same type of orientation relationship with one of the ferrite grains while the other interphase boundary is incoherent.

The isothermal kinetics of the austenite precipitation can be expressed by an Avrami-type equation [SOU 80]. However, under non-isothermal conditions, the cooling rate has a great effect on the morphology and amount of precipitated austenite. Widmanstätten-type growth takes place below 1,000°C [OHM 95] and it has been reported that it can be suppressed in a deformed microstructure when cooling at a rate higher than 2°C/s. However, in the absence of deformation high cooling rates enhance such types of transformation [KAU 93].

Atamert and King [ATA 92] devised an equation for welding by relating the volume fraction of austenite to the difference between Creq and Nieq and the cooling time between 1,250 and 800°C. Similar approaches or continuous cooling-phase transformation models allow us to predict the fraction of austenite after continuous/ingot casting [GOB 07]. However, it should be noted that, when the as-cast material is cooled and subsequently reheated at a high temperature before hot working, the relevant microstructure is the actual structure present at this stage and evolving throughout the whole process.

1.3. Microstructural evolution during hot working

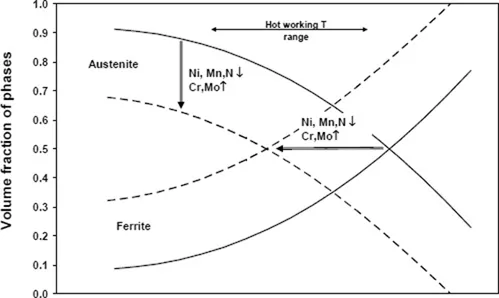

The process of industrial hot rolling begins with a reheating stage at around 1,250°C [BOT 96, DUP 02A]. This stage acts as a solution treatment leading to a certain phase balance depending on the steel composition, as seen in Figure 1.4. However, given that an important fraction of austenite remains undissolved at reheating temperatures for commercial compositions, the as-cast microstructure is preserved to some extent. Increasing the holding time has been reported to induce a degree of globulization of the austenite phase [GOB 07].

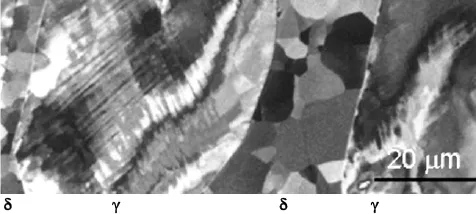

Hot rolling transforms this microstructure to a planar linear configuration, as illustrated in Figure 1.2b. After a 70% hot rolling reduction, the microstructure has a fibrous appearance throughout the longitudinal section: long austenite stringers distributed in a ferritic matrix. In other sections, the austenite appears more dispersedly distributed. The size of the austenite stringers and the separation between them vary from region to region. Additionally, at certain locations, some units lose the general alignment and/or present a blocky aspect. Lower rolling reductions produce microstructures that are midway between as-cast and the wrought one shown in Figure 1.2b.

Although the development of an oriented microstructure is the most evident microstructural change produced by hot rolling, a detailed analysis of the evolution of a duplex microstructure requires at least three different levels:

– distribution, shape, volume fraction, and phase size;

– interphase boundaries and eventual orientation relationships;

– grain microstructure within each phase and associated textures and/or mesotextures.

1.3.1. Changes in morphology and distribution of the dispersed γ phase

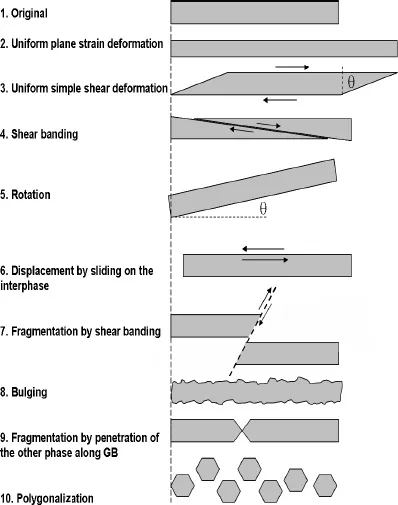

The use of marked specimens to perform thermomechanical simulations in the laboratory, followed by microstructural observations [PIÑ 99, PIÑ 00A] enabled the identification of several mechanisms that modify the shape and distribution of the austenite. Some of the mechanisms listed in Figure 1.5 account for plastic deformation, whereas others are the result of strain partitioning, strain localization, some phase accommodation, and microstructural changes towards equilibrium.

1.3.2. Plastic deformation

Plane strain and pure shear are the only mechanisms that account for the uniform plastic deformation of both ferrite and austenite. The microstructural evolution taking place during hot working within both phases in a duplex microstructure can significantly differ from that observed in single-phase materials. This is because, in addition to their respective high (ferrite) and low (austenite) stacking fault energies, other factors, such as relative strength, morphology, and strain partitioning, also play an important role.

Ferrite: Ferritic stainless steels undergo dynamic recovery [SEL 76, MCQ 96, URC 87, EVA 91, LOM 81] and develop a well-defined subgrain microstructure quite early that remains equiaxed and of constant size once a steady state is reached. In an austeno-ferritic microstructure, dynamic recovery is the primary softening mechanism activated in ferrite [IZA 97B, CIZ 06, DEH 07], see subgrains in Figure 1.6. The ferrite substructure becomes more polygonalized at higher deformations and low strain rates. However, the interphase boundary imposes some restrictions and, as the strain increases, ferrite becomes partially entrapped between γ stringers. The thickness of ferrite (distance between γ stringers) decreases with increasing strain, until it becomes comparable with the ferrite subgrain size.

This is a quite heterogenous process that leads to a bamboo-type structure, as illustrated in Figure 1.7, forming narrow bands of ferrite, limited laterally by the interphase boundaries and subdivided by a mixture of low and high-angle ferrite-ferrite boundaries. The mechanism responsible for the formation of high-angle homophase boundaries in ferrite has been attributed to continuous dynamic recrystallization [IZA 97B, DEH 07], geometric dynamic recrystallization [EVA 04], or extended dynamic recovery [CIZ 06].