eBook - ePub

Socrates

About this book

Socrates presents a compelling case for some life-changing conclusions that follow from a close reading of Socrates' arguments.

- Offers a highly original study of Socrates and his thought, accessible to contemporary readers

- Argues that through studying Socrates we can learn practical wisdom to apply to our lives

- Lovingly crafted with humour, thought-experiments and literary references (from the Iliad to Harry Potter ), and with close reading sof key Socratic arguments

- Aids readers with diagrams to make clear complex arguments

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

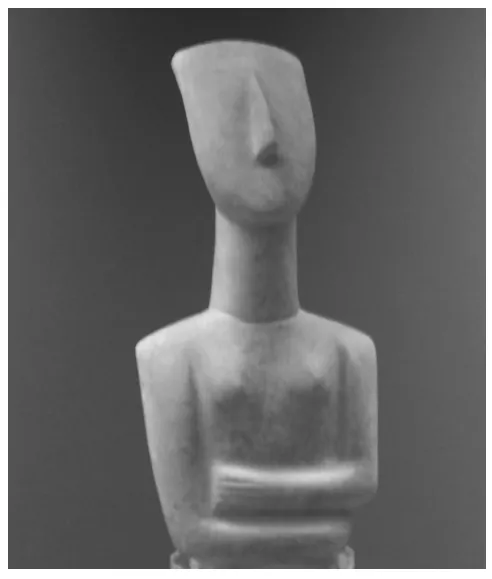

Statue in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, made 3500 BCE in the Cyclades Islands. Photograph taken by author. The statue, arms over chest, is in the position of a dead body in burial, suggesting a body without a soul. There are other remarkable features: the statue is feminine (as souls are in Greek language), with an elongated neck, over-sized and mis-shaped head, and absent eyes in a face that by its posture nonetheless seems to be looking at something. All these features make the statue less a representation of a body than of that which is perceptive when dissociated from the body, namely, a soul viewing the transcendent. As I interpret Socrates, it was the nature of his soul, most distinctively, to see the transcendent in human life. In this way the image, though predating Socrates by 2000 years, gives us a picture of his very soul.

This edition first published 2009

© 2009 George Rudebusch

© 2009 George Rudebusch

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007.

Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at http://www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of George Rudebusch to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rudebusch, George, 1957–

Socrates / George Rudebusch.

p. cm. – (Blackwell great minds)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-5085-9 (hardcover: alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4051-5086-6

(pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Socrates. I. Title.

B317.R83 2009

183′.2–dc22

2009007107

Socrates / George Rudebusch.

p. cm. – (Blackwell great minds)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-5085-9 (hardcover: alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4051-5086-6

(pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Socrates. I. Title.

B317.R83 2009

183′.2–dc22

2009007107

blackwell great minds

edited by Steven Nadler

The Blackwell Great Minds series gives readers a strong sense of the fundamental views of the great western thinkers and captures the relevance of these figures to the way we think and live today.

1 Kant by Allen W. Wood

2 Augustine by Gareth B. Matthews

3 Descartes by André Gombay

4 Sartre by Katherine J. Morris

5 Charles Darwin by Michael Ruse

6 Schopenhauer by Robert Wicks

7 Shakespeare’s Ideas by David Bevington

8 Camus by David Sherman

9 Kierkegaard by M. Jamie Ferreira

10 Mill by Wendy Donner and Richard Fumerton

11 Socrates by George Rudebusch

Forthcoming

Aristotle by Jennifer Whiting

Nietzsche by Richard Schacht

Plato by Paul Woodruff

Spinoza by Don Garrett

Wittgenstein by Hans Sluga

Heidegger by Taylor Carman

Maimonides by Tamar Rudavsky

Berkeley by Margaret Atherton

Leibniz by Christa Mercer

Hume by Stephen Buckle

Hobbes by Edwin Curley

Locke by Samuel Rickless

To

Hope

acknowledgments

Socrates was not entirely successful in saving Athens from its anti-philosophical ways, yet nonetheless Athens owed him thanks. Likewise a number of readers have not entirely succeeded in saving this book from error, yet nonetheless I owe them thanks. Brian Hutler – with his genius for philosophy, his savvy as a manuscript reviewer, his devoted and detailed comments on each chapter as I first drafted it, and his final review of the whole – has played the greatest role in leading me to improve content, structure, and style.

In addition Kofi Ackah, Ashraf Adeel, Mark Budolfson, Mehmet Erginel, Gale Justin, José Lourenço, Fernando Muniz, Debra Nails, Hope Lindsay Rudebusch, and Christopher Turner each gave me a critical review of the entire book and comments that led to substantial changes. For astute help at various points, I thank Michael Baun, Betty Belfiore, Jeffrey Downard, Gail Fine, Steven Funk, Chris Griffin, Stephen Halliwell, Matthew Herbert, Adam Hutler, Rachana Kamtekar, Joe Lauer, Mark McPherran, Sara Rappe, Naomi Reshotko, Nicholas D. Smith, and Mike Stallard. For encouraging me at the outset to undertake the project, I thank Georgios Anagnostopoulos, Julia Annas, Terry Penner, and Gerasimos Santas. Finally, I thank Nick Bellorini, who visited me in Flagstaff and first proposed the project to me in his capacity as editor for Blackwell.

I wrote the bulk of this book while on sabbatical from Northern Arizona University in the academic year 2006–7. Jess Lorona, as an attorney’s professional courtesy, provided funding that enabled me to take the whole year for the project. I am grateful for this institutional and personal financial support.

In preparing to write this book, I benefited from the opportunity to make presentations and participate in discussions. For these benefits I am grateful both to the individuals who organized the meetings as well as to the institutions supporting my travel. I thank especially Mark McPherran for organizing each spring in Tucson the Arizona Plato Colloquium, and also Georgios Anagnostopoulos, Julia Annas, Tom Christiano, Chris Maloney, Fernando Muniz, and Terry Penner for bringing me to meetings that were crucial to the development of my ideas. For travel funding, I thank in particular my home institution, Northern Arizona University, and also the University of Arizona. In addition I thank the Olympic Center for Philosophy and Culture in Pyrgos, Greece, the A. G. Leventis Foundation in Nicosia, Cyprus, and the CAPES Foundation of the Brazilian Ministry of Education for their support of my travel to international meetings.

Three chapters are revisions of work published elsewhere. Chapter 7, “Puzzling Pedagogy,” is a revision of “Socrates, Wisdom and Pedagogy,” Philosophical Inquiry [Athens]: Festschrift in Honor of Gerasimos Santas, edited by G. Anagnostopoulos, vol. 30 no. 3–4 (2008) 1–21. Chapter 8, “Love,” is a revision of “Socratic Love,” in The Blackwell Companion to Socrates, edited by R. Kamtekar and S. Ahbel-Rappe, London and New York: Blackwell (2006) 186–99. Chapter 11, “Benevolence,” is a revision of “Neutralism in Book I of the Republic,” in The Good and the Form of the Good, edited by D. Cairns, F.-G. Herrmann, and T. Penner, Edinburgh University Press (2007) 76–92. I am grateful to these publishers and their editors for permission to use these works in revision.

translations used

Unattributed translations are mine, except for Bible translations, which are from the New American Standard. The line references I use are standard and should give the reader little trouble.

introduction

Goals of This Book

Plato’s dialogues tell a story about Socrates’ life, focusing on conversations about human excellence. This book follows that life from age 36 to age 70, from mastery over the “wisest man” Protagoras to death by poison. In those conversations, the conclusions Socrates reaches – sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly – are wild:

- No human being knows how to live.

- Bravery, benevolence, righteousness, reverence, the best sort of luck – even the ability to interpret the most divine poetry – are all one and the same thing: expertise at human well-being.

- Such expertise by itself would requite the needy love of any human being, rule the psyche (or soul, as I shall call it) without inner conflict, and ensure happiness and freedom.

- Lacking that expertise, we are guilty of the worst sort of negligence if we do not spend our lives trying to discover it – better not to live at all!

Socrates’ arguments eliciting these results are open to obvious objections. Readers who take the objections to be successful have two interpretive options. One is to suppose that Socrates spent his life fascinated by what we easily see to be poor arguments. The second option is to suppose that Socrates did not intend such arguments seriously, but was being playful for some reason or other.

I propose a third option. Finding convincing replies to the obvious objections, I take Socrates’ results seriously and endorse the interpretation Alcibiades gives in Plato’s Symposium. Alcibiades compares Socrates’ arguments to “those statues of Silenus that open down the middle” (221d8–e1). This Silenus was a satyr, a mythical creature having a distorted human face and upper body, with the lower body of a goat. Silenus was ridiculous as a lusting drunkard, ever driven by sexual desire and incapable of sober thought – yet these very acts were his worship of the god Dionysus. Hidden inside the grotesque hollow statue was a beautiful agalma, that is, a holy image of the god, carved as an act of worship. The agalma would delight the lucky person who found it inside. Just so, Alcibiades says,

Socrates’ arguments seem ridiculous the first time you listen… but if you see them taken apart and get inside of them, you will find them to be the only arguments that are reasonable, arguments that are the most godlike, arguments holding inside a wealth of agalmata of divine excellence, arguments that are largely – no, completely – intent on everything proper for becoming a noble and good man.

221e1–222a4

I follow Alcibiades, seeing in Socrates’ arguments the power to bring joy and propriety to human lives.

I emphasize that there are alternatives to my interpretation. While some commentators prefer the first two options I mention above, others prefer a fourth option, which is to take Socrates’ arguments seriously, but to give tame interpretations of his conclusions. For example, some have interpreted the wild idea that expertise ensures happiness as the tame conventional wisdom that good people make the best of their circumstances. The wild idea that any life that does not consist of philosophical examination is not worth living becomes the tame advice that an examined life is the only hope for improving ourselves. Such taming has advantages: it both judges Socrates’ arguments to be good and at the same time leaves conventional moral wisdom unthreatened. Nonetheless, I urge that we recognize the possibility of a deeper and truer moral sensibility than conventional wisdom. Rather than construe Socrates’ view in the manner most plausible by our lights, my goal is to find what in Socratic argument will compel our assent, even if it turns human life upside down.

Thus 14 chapters that follow aim to show how Socrates gives compelling arguments for wild conclusions. Upon hearing Socrates in the Gorgias, Callicles appropriately replied: “If what you say turns out to be true, aren’t we human beings living our lives upside down and doing everything quite the opposite of what we ought?” (481c2–5). I agree with Callicles that everything important in human life hangs on the question whether Socrates’ views are true.

Socrates speaks to us in ordinary language as human beings, not as academic specialists. It is not rocket science, but it is a philosophical project. Socrates’ method – beginning from premises accepted by his conversation partner and arguing step by step in ordinary language – to a large degree created the academic discipline of philosophy in European history. Plato and Aristotle took up many of the topics investigated by Socrates, and those topics have remained essential in the academic tradition of western philosophy. People to this day who have had only one philosophy course are more likely to have read a Socratic dialogue than anything else.

In my opinion the philosophical tradition has not given Socrates’ results the attention they deserve. His results are as surprising today as they were in his day. Yet it would be difficult to overstate how much my project depends upon a half-century of scholarship that uses the tools of analytic philosophy to interpret and evaluate the premises, inferences, and conclusions of Socratic arguments.

In addition to my goal of providing to readers a conversation with a philosophically astute Socrates, I have another goal. This is to recognize Socrates the Philosopher as one of the great religious inspirations of world history, comparable to such others as Confucius the Master, Krishna the Lord, Siddhartha the Buddha, Jesus the Christ, and Mohammad the Prophet – as they are called by their devotees. These cultural fountainheads make different and sometimes incompatible statements about supernatural beings and the institution of religion in society. But they share the theme that single-minded devotion to righteousness, done as a holy sacrament, is ideal life. In chapters 15 and 16 I propose a life of Socratic philosophy not as an alternative to the life of religious devotion but as itself the heavenly way for human beings to live, through the sacrament of cross-examination about human excellence.

To a far greater extent than other religious teachers, we possess in Plato’s dialogues step-by-step arguments aimed at demonstrating the truth of their shared theme. It is by considering objections and replies to these arguments that I propose to help readers decide its truth. To put it grandly, my goal is to lead philosophers to religion, to lead the religious to philosophy, and to lead those who are neither to both.

Who Was Socrates?

The Confucius, Siddhartha, and Jesus who have shaped world history are the characters preserved in classic texts. It is a matter of doubt to what degree those texts accurately present historical persons. Likewise the Socrates who has greatly influenced the course of history is the character we find in Plato’s dialogues. This Socrates in some ways (but not others) is similar to the Socrates presented in other ancient texts, most extensively in Aristophanes and Xenophon.

Readers want to know to what degree Plato’s Socrates is fictional and whether in important ways he is the historical figure. I save that question for the epilogue. It is appropriate to put that question last, not first, in this book. The important question for this book – like the important question for us as human beings – is not the particular flesh and blood who uttered these words but the great mind in the text for us to understand, whether that mind is a literary creation or a historically accurate account.

I sometimes (such as in chapter 5) contrast views of Socrates as he appears in different dialogues written by Plato. It is confusing to speak of Socrates and “another Socrates.” Following Aristotle, I refer to the other Socrates as Plato, even when the other Socrates speaks in the same dialogue with Socrates (as in chapter 16)! In the epilogue I defend the use of Aristotle’s distinction as a working hypothesis. But none of the book’s goals requires that the distinction between Socrates and the other Socrates be more than a convenience for talking about different threads of discussion found in Plato’s dialogues.

the ion

chapter 1

interpreting socrates

What does it take properly to interpret Socrates? A conversation that Socrates has at age 56 tells us. The conversation is wi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page 1

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Series Page 2

- Dedication

- acknowledgments

- translations used

- Introduction

- the ion

- the apology

- the protagoras

- the laches

- the lysis

- the euthydemus

- the meno

- book 1 of the republic

- the euthyphro

- the crito

- the phaedo

- epilogue: socrates or plato?

- index of passages cited

- general index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Socrates by George Rudebusch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ancient & Classical Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.