- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written by one of the world's leading neuroscientists, Making Up the Mind is the first accessible account of experimental studies showing how the brain creates our mental world.

- Uses evidence from brain imaging, psychological experiments and studies of patients to explore the relationship between the mind and the brain

- Demonstrates that our knowledge of both the mental and physical comes to us through models created by our brain

- Shows how the brain makes communication of ideas from one mind to another possible

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making up the Mind by Chris Frith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Seeing through the Brain’s Illusions

Chapter 1

Clues from a Damaged Brain

Sensing the Physical World

Chemistry was my worst subject at school. The only bit of science I remember from those lessons was a trick to use in practicals. You are confronted with a lot of little dishes of white powder that you are supposed to identify. Try tasting them. The one that tastes sweet is lead acetate. Just don’t taste too much of it.

This is the ordinary person’s approach to chemistry, usually applied to the contents of those jars at the back of the kitchen cupboard. If you can’t tell what it is by looking at it, then try tasting it. This is how we find out about the physical world. We explore it with our senses.

It follows that, if your senses are damaged, then your ability to explore the physical world will be reduced. You are probably short-sighted.1 If I ask you to take your glasses off and look around, you will no longer be able to identify small objects that are more than a few feet away. This observation is not very surprising. It is our sense organs, eyes, ears, tongue, etc., that provide the link between the physical world and our minds. Just like a video recorder, our eyes and ears pick up information2 about the physical world and transmit it to our minds. If our eyes or ears are damaged, then the information can no longer be transmitted properly. It will not be so easy for us to find out about the world.

The problem becomes more interesting when we start to wonder how the information gets from the eyes to the mind. Let us for the moment suppress our worry about how electrical activity in a photo-receptor in the eye3 gets turned into a mental experience of color and simply note that the information from my eye (and ear and tongue, etc.) goes to my brain. It follows that damage to my brain can also reduce my ability to find out about the physical world.

Figure 1.1 The retina, where light creates brain activity

The retina at the back of the eye contains large number of special neurons (photo-receptors) that become active when struck by light. In the middle of the retina (the fovea) are the cones. There are three kinds of cone that are activated by different wavelengths of light (corresponding to red, green, and blue). Around the fovea are the rods that respond to dim light of any color. All theses cells send signals via the optic nerve to the visual cortex.

The retina at the back of the eye contains large number of special neurons (photo-receptors) that become active when struck by light. In the middle of the retina (the fovea) are the cones. There are three kinds of cone that are activated by different wavelengths of light (corresponding to red, green, and blue). Around the fovea are the rods that respond to dim light of any color. All theses cells send signals via the optic nerve to the visual cortex.

Source: Prof. W.S. Stark, Biology, St. Louis University, Missouri.

The Mind and the Brain

Before we explore how brain damage can affect our experience of the world, we need to worry a bit more about the relationship between the mind and the brain. The relationship must be close. As we discovered in the Prologue, if I decide to think about a face, then a specific “face” area in my brain will become active. In this example, knowing about the contents of my mind has enabled me to predict which brain area will be active. As we shall discover in a moment, damage to the brain can have profound effects on the mind. Indeed, knowing where the brain has been damaged enables me to predict the contents of the person’s mind. But the relationship between brain and mind is not perfect. It is not one-to-one. There can be changes in the activity in my brain without any changes in my mind. On the other hand I firmly believe that there cannot be changes in my mind without there also being changes in brain activity.4 This is because I believe that everything that happens in my mind (mental activity) is caused by, or at least depends upon, brain activity.5

So, if my belief is correct, the chain of events would be something like this. Light strikes the sensory receptors in my eye causing the receptors to send messages to brain. This mechanism is pretty well understood. Then the activity in the brain somehow creates the experience of color and shape in my mind. This mechanism is not understood at all. But, whatever the mechanism, we can conclude that my mind can have no knowledge about the physical world that isn’t somehow represented in the brain.6 I can only know about that world through my brain. So perhaps the question we should be asking is not, “How do I (or how does my mind) know about the physical world?” Instead we should ask “How does my brain know about the physical world?”7 By asking the question about the brain, rather than the mind, I can put off for a moment the problem of how knowledge about the physical world gets into my mind. Unfortunately this trick doesn’t really work. The first thing I would do if I wanted to find out what your brain knew about the outside would be to ask you, “What can you see?” I am using your mind to find out what’s represented in your brain. As we shall see, this method doesn’t always work.

When the Brain Doesn’t Know

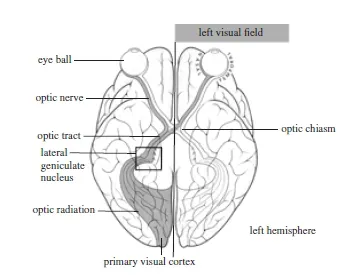

Of all the sensory systems in the brain, we know most about the visual system.8 The visual world is first represented in the neurons at the back of the retina. Just as in a camera, the image is upside-down and mirrorreversed, so that neurons at the top left of the retina represent the bottom right of the visual scene. The retina sends signals to the primary visual cortex (V1) at the back of the brain via the thalamus, a sensory relay station in the middle of the brain. The neurons conveying the signal partially cross over, so that the left side of each eye is represented in the right half of the brain, and vice versa. The “photographic” image is retained in the primary visual cortex,9 so that neurons at the top left of the cortical area represent the bottom right of the visual scene.

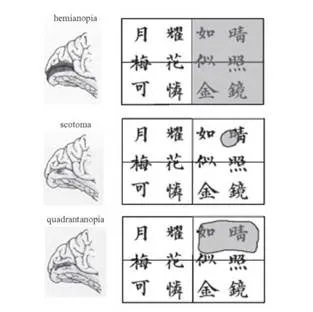

The effect of damage to the primary visual cortex depends upon where the damage occurs. If the top left region of the visual cortex is damaged, then the sufferer will experience a blank area in the bottom right of the visual scene. In this part of the visual field they are blind.

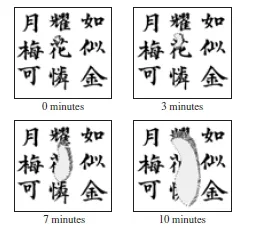

Some people who suffer from migraines experience brief periods in which part of the visual field goes blank due to a temporary reduction of blood supply to the visual cortex. The experience often starts with a small blank area that gradually gets larger and larger. The blank area is often edged by flashing zig-zag lines described as fortifications.

Before information in the primary visual cortex is passed on to the next processing stage in the brain, the visual scene is deconstructed into different features such as shape, color, and motion. These different features are passed on to different brain areas. In rare cases damage can occur to brain regions concerned with just one of these specific features while all other areas remain intact. If the color area (V4) is damaged, then the sufferer sees the world drained of color (achromatopsia). Since we have all seen black and white films and photographs, this experience is not too difficult to imagine. It is more difficult to imagine the world of someone with damage to the visual movement area (V5). From one moment to the next, objects, such as cars, will appear in different positions – but they don’t appear to move (akinetopsia). This experience must be something like the opposite of the waterfall illusion that I mentioned in the Prologue. In that illusion, which we can all experience, objects stay in the same place from one moment to the next, but we still see movement.

Figure 1.2 How neural activity gets from the retina to the visual cortex Light from the left side of the visual field goes to the right hemisphere. The brain is seen from underneath.

Source: Figure 3.3 in: Zeki, S. (1993). A vision of the brain. Oxford, Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Figure 1.3 How damage to the visual cortex affects experience Damage to the visual cortex causes blindness in specific regions of the visual field. Loss of the whole of the right visual cortex causes blindness in the left visual field (hemianopia). Loss of a small area in the lower right visual cortex causes a spot of blindness in the upper left visual field (scotoma). Loss of the whole of the lower right visual cortex cause blindness in the upper right visual field (quadrantanopia).

Source: From Figure 3.7 in: Zeki, S. (1993). A vision of the brain. Oxford, Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Figure 1.4 The development of a migraine, described by Karl Lashley At the beginning of his migraine an area of blindness appeared near the middle of his visual field and then slowly increased in size.

Source: Lashley, K. (1941). Patterns of cerebral integration indicated by scotomas of migraine. Archives of Neurological Psychiatry, 46, 331–339.

At the next stage of visual processing, information from features such as shape and color is recombined in order to recognize the objects in the visual scene. The brain regions where this occurs can sometimes be damaged while the earlier visual processing regions remain intact. Some people with this condition have a general problem recognizing objects. They can see and describe the various features of the object, but they don’t know what the object is. This problem is referred to as “agnosia” or loss of knowledge.10 The basic sensory information is available, but it can no longer be understood. Sometimes these people have a specific problem with faces (prosopagnosia). They know it’s a face, but they have no idea whose face it is. These people have damage to the face area that I described in the Prologue.

These observations all seem straightforward. Damage to the brain interferes with the transmission of information picked up by our senses from the physical world. The effect upon what our mind can know about the world is determined by the stage in transmission at which the damage occurs. But sometimes the brain plays tricks on us.

When the Brain Knows, But Doesn’t Tell

It is the dream of every neuropsychologist11 to discover someone who has such an unusual view of the world that we are forced to reconsider our ideas about how the brain works. Two things are necessary to discover such a person. First, we have to be lucky enough to meet him or her. Second, we have to be clever enough to recognize the importance of what we are observing.

“I’m sure you’re both lucky and clever,” says the Professor of English.

Not so. I was lucky once, but not clever. As a young research worker at the Institute of Psychiatry in south London, I was studying how people learn. I was introduced to someone with severe loss of memory. For a week he visited my lab12 every day in order to learn a simple motor skill. His performance improved in a fairly normal manner and even after a gap of a week he retained the new skill he had learned. But, at the same time, his memory loss was so severe that each day he would claim that he had never met me before and had never performed the task before. “How strange!” I thought. But I was interested in problems of motor skill learning. This man learned the skill I taught him normally and so I wasn’t interested in him. Many others have, of course, recognized the importance of people like this. Such people can remember nothing that has happened to them even if it happened only yesterday. We assumed that this was because the events that happened were not recorded in the brain. But, in the person I studied, the experiences he had yesterday clearly had a long-term effect on his brain since he was able to perform the motor task better today than yesterday. But this long-term change in the brain had no effect on his conscious mind. He could not remember anything that happened yesterday. Such people show that our brain can know things about the world that our mind does not know.

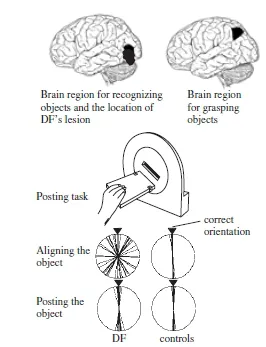

Mel Goodale and David Milner made no mistake when they met the person known as DF. They immediately recognized the importance of what they were observing. DF had the misfortune to suffer from carbon monoxide poisoning as the result of a faulty water heater. The poisoning damaged part of the visual system of her brain concerned with the recognition of shape. She has a vague impression of light, shade, and color, but cannot recognize anything because she can’t see what shape it is. Goodale and Milner noticed that she seemed to be able to walk around and pick things up far better than would be expected given that she was nearly blind. Over the years they have performed a whole series of experiments with her. These confirm that there is a big discrepancy between what she can see and what she can do.

One of Goodale and Milner’s experiments works like this. You hold up a rod and ask DF about its orientation. She cannot say whether it is horizontal or vertical or at an angle. It is as if she cannot see the rod and is just guessing. Then you ask her to reach out and grasp the rod. She does this normally. She rotates her hand so that her fingers have the same orientation as the rod. She grasps the rod smoothly whatever its angle. This observation shows that DF’s brain “knows” about the angle of the rod and can use this information to control the movements of her hand. But DF can’t use this information to see the orientation of the rod. Her brain knows something about the physical world, while her conscious mind does not.

Very few people have been found with precisely the same problem as DF. But there are many people with brain damage where the brain plays similar tricks. Probably the most spectacular dissociation is seen in people with “blindsight,” a problem associated with damage to the primary visual cortex. As we already discovered, this damage causes the person to become blind for part of the visual field. Larry Weiskrantz was the first to show that, in a few people, this blind area is not truly blind after all.13 In one experiment a spot of light is moved slowly across the part of the visual field that is blind and the participant is asked to report what he sees. As far as this participant is concerned, this is an extremely stupid task. He can’t see anything. So instead he is asked to guess, “Was the spot moving right or left?” This also seems a fairly stupid task, but the participant assumes that this eminent Oxford professor knows what he is doing. Professor Weiskrantz discovered that some people could guess much better than chance. In one experiment a participant was correct more than 80% of the time, while still claiming to see nothing. So, if I suffered from blindsight, my mind could have absolutely no visual content and yet my brain would know things about the visual world and could somehow enable me to make accurate “guesses” about that visual world. What sort of knowledge is this that I don’t know I have?

Figure 1.5 Action without awareness DF has a lesion in the part of her brain necessary for recognizing objects, while the part of her brain necessary for grasping is intact. She can’t see whether or not the “letter” is lined up with the slot. But she can orient the “letter” when she posts it through the slot.

Source: Lesion location: Plate 7; posting data: Figure 2.2 in Goodale, M.A. & Milner, A.D. (2004). Sight unseen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

When the Brain Tells Lies

At least the unknown knowledge of the person with blindsight is correct. Sometimes brain damage can cause the mind to have information about the physical world that is completely false. A deaf old lady was woken up in the middle of the night by loud music. She searched her flat for the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Abbreviations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: Real Scientists Don’t Study the Mind

- Part I: Seeing through the Brain’s Illusions

- Part II: How the Brain Does It

- Part III: Culture and the Brain

- Epilogue: Me and My Brain

- The Evidence

- Illustrations and Text Credits

- Index