eBook - ePub

Kellogg on Branding

The Marketing Faculty of The Kellogg School of Management

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kellogg on Branding

The Marketing Faculty of The Kellogg School of Management

About this book

The Foreword by renowned marketing guru Philip Kotler sets the stage for a comprehensive review of the latest strategies for building, leveraging, and rejuvenating brands. Destined to become a marketing classic, Kellogg on Branding includes chapters written by respected Kellogg marketing professors and managers of successful companies. It includes:

- The latest thinking on key branding concepts, including brand positioning and design

- Strategies for launching new brands, leveraging existing brands, and managing a brand portfolio

- Techniques for building a brand-centered organization

- Insights from senior managers who have fought branding battles and won

This is the first book on branding from the faculty of the Kellogg School, the respected resource for dynamic marketing information for today's ever-changing and challenging environment. Kellogg is the brand that executives and marketing managers trust for definitive information on proven approaches for solving marketing dilemmas and seizing marketing opportunities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kellogg on Branding by Alice M. Tybout, Tim Calkins, Alice M. Tybout,Tim Calkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Digital Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION III

FROM STRATEGY TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHAPTER 7

BUILDING BRANDS THROUGH EFFECTIVE ADVERTISING

BRIAN STERNTHAL and ANGELA Y. LEE

For the past several years, media analysts have predicted the demise of advertising—television advertising in particular. In today’s world, media are fractured. With so many media choices, it is often difficult to attract a substantial audience for any one vehicle. Network television that once reached over 90 percent of Americans now reaches less than half that number. In 1965, 80 percent of Americans could be reached by three TV spots, whereas today it would require 97 spots. Magazines have proliferated, custom publishing has flourished, signage has grown substantially, and new media such as Internet advertising have emerged.

Not only are viewers’ media choices more diverse, but the audience is more diverse as well. African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics now account for approximately 30 percent of the American population, and often have unique consumption habits and motivations. Another recent trend is the decline in television viewing by the key 18- to 34-year-old market and the daytime viewing audience. And even among those who have sustained their viewing habits, TiVo and other digital video recording devices make it easy to skip the normal viewing of commercials.

Despite these concerns, advertising expenditures have been growing at a steady rate. In 2004, ad spending growth was about 8 percent, while Internet and cable television advertising spending saw double-digit growth. Thus, it appears that the forecasted demise of advertising runs afoul of fact. However, the advertising landscape is definitely changing. Growing numbers of advertisers with large budgets are focusing their spending on building relationships with current heavy users of their brands. This strategy has greatly affected media choices, leading to the emergence of custom publishing materials and other direct marketing vehicles, the use of event marketing and other personal contact approaches, and the increasing and more selective use of product placement.

These developments mean that all advertisers must be concerned about the effective use of their advertising dollars. Customer insight is one starting point for developing effective advertising strategy. These insights pertain to what customers think and how people use information to evaluate products and make brand choice decisions (see Chapter 3).

In this chapter, we focus our attention on the how element of this equation—how people process advertising messages. We describe a processing model for advertising exposure, then discuss how advertising influences customers’ product judgments and brand choices. We then present an analysis of media strategies that help brands shout with a dominant voice. In the final section, we discuss approaches to measuring advertising effectiveness.

AN INFORMATION-PROCESSING MODEL OF ADVERTISING EXPOSURE

Although it seems intuitive that consumers would choose a brand based on an objective evaluation of the information they receive about a product, this is not always the case. People may purchase a brand because it comes to mind most readily, or because it is the brand their mother always bought, or because the brand is the easiest to justify to others.

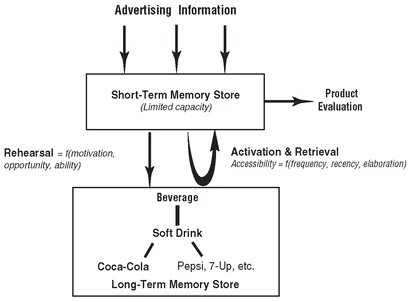

Advertising content is thought to influence brand judgments through a two-stage process. As is schematically depicted in Figure 7.1, advertising information is first encoded and represented more or less faithfully in the short-term memory store. This information reflects what a consumer is thinking at the moment when he or she sees an ad. The short-term memory store has a limited capacity—it can only hold a limited amount of information for a short period of time. If there is no further processing of the advertising message, the information will be lost.

With sufficient elaboration or repetition, the information in the short-term store will be transferred to the long-term memory store, which is the repository of all processed information. The long-term store’s defining characteristic is its organization. Information in long-term memory is stored in clusters known as networks of associations. Each piece of information is called a node; for example, brands are stored in long-term memory as brand nodes. Nodes are hierarchically organized into categories and subcategories.

Figure 7.1

An Information-Processing Model of Advertising Exposure

An Information-Processing Model of Advertising Exposure

For example, Coca-Cola is represented in memory by a particular node. This node is a member of the category soft drink, which in turn is a member of the superordinate category beverage. Each brand and category can have different kinds of associations. The associations that advertisers often focus on to infer the brand’s benefits include attributes (e.g., caramel color), users (e.g., young adults), and occasions of use (e.g., sports events).

The content of an advertising message is usually encoded in short-term memory. The encoding typically involves the automatic activation of prior knowledge from long-term memory that is part of the associative network. These associative inferences help people make sense of the message. However, not all information from the long-term store is activated. This occurs because long-term memory is the repository of all information that a person has processed, but the short-term store has a highly limited capacity to receive information. Therefore, only certain nodes of the long-term store are activated and represented in short-term memory. This raises the question of what prior knowledge might be activated when a person is first exposed to an advertising message. Answering this question is critical for marketers: If an advertiser can determine what references a consumer might call up when exposed to an advertising message, then ads can be most effectively created for maximum impact and long-term association.

Three factors influence the activation of information from the long-term store. The first is the frequency of its processing: The more often a node is activated, the more readily it comes to mind. We all recognize that leading brands are easier to recall than minor brands. The second factor is the recency of information processing: Memory operates on a “last-in, first-out” basis—the most recently processed information is the most likely to be retrieved from long-term memory into short-term memory. For example, we are more likely to remember an ad that we saw last night than one that we saw last month. The third factor is elaboration, which refers to the associations a person makes to a brand. For example, an airline’s convenience may be associated with several factors, including a high number of sought-after destinations, the availability of e-tickets, and the option of curbside check-in. By elaborating on these conveniences in the ad, an airline can prompt the activation of the convenience node in consumers’ minds. Through these associations, customers may conclude that flying with the airline is convenient, although convenience is not explicitly mentioned in the ad. And information elaborated in short-term memory will be transferred to long-term memory.

Thus, advertising affects consumers’ judgment by providing them with information that in turn triggers the retrieval of prior knowledge. Once advertising content and accessible prior knowledge are represented in short-term memory, people may actively process these different pieces of information and form attitudes and opinions about the product by relying on (1) the information presented in the advertising appeal, (2) prior knowledge, or (3) the associations made through processing both advertising and prior knowledge. An understanding of how information from these different sources is used to make decisions offers further insights into how to develop effective advertising.

THE IMPACT OF MESSAGE CONTENT ON JUDGMENTS

The information-processing model of advertising provides the basis for several strategies advertisers can use to optimize the impact of messages advertising their brand.

Aspirations

People are inferential, and they make judgments about advertising based on their aspirations, not on literal information. Thus, a brand’s advertising should reflect consumers’ aspirations. Because advertising information triggers an individual’s own repertoire of relevant information (from short- and long-term memory stores), product judgments are outcomes of inferential rather than literal processing. Inherently, consumers are inferential when they are exposed to advertisements—they infer meaning beyond what is literally presented in an ad. These inferences come from consumers’ own judgments about the information presented; they are often a reflection of consumers’ aspirational selves—the things that each person aspires to in his or her life. Thus, successful advertising often depends on whether individuals’ aspirations are promoted in advertising and not on the information that is literally presented.

For example, older consumers are typically more persuaded by advertising that depicts younger people, and younger children are often persuaded by advertising showing older children. These ads play to the aspirations of their respective audiences (i.e., older people want to be younger; younger people want to be older). In Hallmark greeting card ads targeted at men in their twenties, preteen boys were depicted pondering the dilemma of the best way to ask for a date. This approach reminds the 20-something men how it felt to be younger and just starting to date (without making the ad so emotional that it would make them uncomfortable).

Prior Beliefs

People process advertising with their own filters, and thus advertising content should resonate with prior beliefs. Consumers respond to advertising by activating their own repertoire of knowledge, associating advertising content with the information already in their memory. Thus, it is easier to persuade consumers when advertising information resonates with their accepted beliefs. If consumers believe that honey offers better nutrition than sugar, it is easier to market a brand of cereal that coincides with this category belief (e.g., Honey-Nut Cheerios) than to try to change the belief. This is not to say that attitude change should not be a goal of advertising. But prompting change is likely to require a larger ad budget than strengthening accepted beliefs.

Consumer Goals

People are goal-driven when processing information, and thus advertising content should resonate with existing goals. Effective advertising is not simply a matter of featuring content that is compatible with consumers’ prior beliefs. Effective advertising also involves presenting content that is consistent with consumer goals—and presenting it in a way that corresponds to these goals. People have consumption goals, such as the need to buy a car, a shirt, or a copying machine. Not surprisingly, consumers are more likely to pay attention when advertising helps them pursue these consumption goals.

The term self-regulatory focus refers to people’s internal motivation that governs and regulates their attitudes and behavior as they pursue their consumption goals.1 Two such orientations (or regulatory foci) are important in understanding how people make decisions. One involves the presence and absence of desirable outcomes (termed promotion focus), and the other involves the presence and absence of undesirable outcomes (termed prevention focus). People who are promotion focused have an orientation toward accomplishment, growth, and aspirations, and they pursue their consumption goals with eagerness. These consumers typically view information through the lens of what they will gain or not gain (they are looking to gain). By contrast, those who are prevention focused have an orientation toward safety, security, and responsibilities, and they pursue their consumption goals with caution and vigilance.2 They typically view information through the lens of what they will lose or not lose (they are looking not to lose).

This distinction is important because an individual’s regulatory focus affects the resonance of different types of brand claims. Consider advertising for tampons. One execution shows women swimming and biking and doing other everyday activities during their period (i.e., a promotion-focused message), whereas another shows the accidents that are avoided by using the advertised brand (i.e., a prevention-focused message). Often such executions are aired as part of the same campaign. This practice glosses over an important distinction. If the audience is concerned with aspirations and achievement, the first spot resonates with their promotion focus and is more effective than the second spot. However, if the audience is concerned about safety and security, the second spot appeals to their prevention focus, and thus is more persuasive.3

The distinction between promotion and prevention focus is also useful when deciding how the advertising message should be framed. The way that a message is presented affects its resonance with consumers’ self-regulatory focus and in turn determines how persuasive it is. A promotion message is more persuasive when it emphasizes gain (e.g., eat right and get energized) than when it emphasizes nongain (e.g., you won’t get energized if you don’t eat right), and a prevention message is more persuasive when it emphasizes loss (e.g., you will have clogged arteries if you don’t eat right) than when it emphasizes nonloss (e.g., you won’t get clogged arteries if you eat right).4

Brands often compete by focusing on either a promotion or prevention goal. In the liquid bleach category, for example, Clorox presents its brand as the one that gives the purest clean by providing a brilliant white. Thus, the emphasis is on a promotion goal. By contrast, OxiClean focuses on prevention by positioni...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- PREFACE

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- SECTION I - KEY BRANDING CONCEPTS

- SECTION II - STRATEGIES FOR BUILDING AND LEVERAGING BRANDS

- SECTION III - FROM STRATEGY TO IMPLEMENTATION

- SECTION IV - BRANDING INSIGHTS FROM SENIOR MANAGERS

- INDEX