eBook - ePub

Driving Results Through Social Networks

How Top Organizations Leverage Networks for Performance and Growth

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Driving Results Through Social Networks

How Top Organizations Leverage Networks for Performance and Growth

About this book

Driving Results Through Social Networks shows executives and managers how to obtain substantial performance and innovation impact by better leveraging these traditionally invisible assets. For the past decade, Rob Cross and Robert J. Thomas have worked closely with executives from over a hundred top-level companies and government agencies. In this groundbreaking book, they describe in-depth how these leaders are using network thinking to increase revenues, lower costs, and accelerate innovation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Driving Results Through Social Networks by Robert L. Cross,Robert J. Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Leadership. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

ALIGNMENT

How to Ensure That Networks Support

Strategic Objectives

Strategic Objectives

In a 2006 article published in the Financial Times, business school professor Henry Mintzberg railed against the obsessive focus on individual leaders as the fulcrum of organizational effectiveness: “By focusing on the single person . . . leadership becomes part of the syndrome of individuality that is undermining organizations.” 5 We agree, of course, but to be fair, the fixation on leaders as individual actors results from the lack of an alternative framework. We simply haven’t had a different lens through which we could connect individual efforts and organizational action. Some have turned to elaborate formal structures as a means of connecting individual and organizational behaviors. But formal structures often overlook the fact that every formal organization has in its shadow an informal “invisible” organization. This informal organization, which is brought to light by organizational network analysis (ONA), need not be seen as opposed to the formal organization, but may instead be seen as an answer to the inevitable shortcomings of a formal structure.6

ONA provides leaders with the means to accomplish what is arguably their most critical function: aligning individual and collective action with strategic objectives. Leaders are individuals in a formal structure, but they are also embedded in networks that all too often do not show up on the organization chart. In addition to rendering the invisible visible, a network perspective helps leaders understand how much alignment they actually need. Alignment and collaboration require energy and attention, so indiscriminate efforts to foster collaboration can easily impose high costs on employees in terms of increased e-mail traffic, phone calls, meetings, and travel. Decision makers can become so overwhelmed that they cannot act on commercial opportunities, and entire organizations can get bogged down. For these reasons, leaders need to take a strategic view of exactly what they want to accomplish through networks and then ensure that formal and informal aspects of an organization support critical collaborations.

In Part One, we show how leaders can actively diagnose and align networks with core value propositions and strategic objectives—a process of both increasing collaboration at key points of value creation within a network and decreasing connectivity where it is generating insufficient financial or strategic return.

1

ALIGNING NETWORKS WITH STRATEGIC VALUE PROPOSITIONS

Every day you have conversations at work with peers whose opinions you respect and whose friendships you value. It is likely that you report to a superior whom you also like and respect but often do not see for days and sometimes weeks at a time. Both interactions have impact, but the first conversation is “invisible” on most organization charts. Formal structure determines in large part who is sought out in networks: we are driven to reach out to people by virtue of the decisions they get to make, the information they hold, and the resources they dole out. But informal relationships are crucial as well: some people may lack formal authority but possess technical expertise and organizational wisdom, or they may simply be likable and dependable and so an important source of help and information.

Although these networks of both formal and informal relationships are increasingly the conduits through which value is created and innovation realized, most leaders still rely too heavily on formal structure when designing their organizations and implementing strategy. The process of moving boxes and lines around on a formal chart can make leaders feel as though they are driving alignment and organizational focus on strategic objectives, but in fact these formal changes often do not shift the underlying networks. The result is a disconnect between strategic objectives and network configuration that leads organizations to underperform relative to the expertise and resources they possess, or to create unmanageable collaborative demands with efforts that indiscriminately connect people. When, however, leaders employ a network perspective, they can ensure that collaborations deep within the organization are supporting strategic objectives as efficiently as possible.

Consider the story of a $1 billion provider of information technology consulting services with ten thousand employees spread across more than seventy offices globally. In late 2005 the company launched a strategic initiative to move from a branch-and region-centric structure to a matrix organization with globally integrated business lines and vertical consulting practices working in conjunction with a regionally based sales force. The strategic reason for this change was to better focus the company on clients while also increasing scalability, reducing costs, accelerating growth, and improving career opportunities. Management had an aggressive timeline for the transformation, expecting the majority of the restructuring to be completed by mid-2006 and to be fully operational by the end of the year.

To establish a baseline of the firm’s ability to work across boundaries, the senior vice president of human resources conducted an ONA of the top 250 executives and managers. The assessment, which mapped both information flow and revenue-producing collaborations, revealed a number of ways in which this network was potentially misaligned with the strategic intent of the new matrix organization. For example, the information flow network revealed that employees relied heavily on senior leaders. Those lower in the hierarchy—who had critical expertise and key relationships with clients—tended to be on the outer rings of the network and so were not bringing the best expertise of the firm to bear on client sales and project execution. These people were often the single point of contact with key accounts, and they typically had a substantial—but to this point unrecognized—impact on revenue when they left the firm.

The ONA also revealed that several silos in the network were likely to undercut the organization’s ability to realize benefits from the new matrix structure. For example, most collaboration occurred first within a region and then within a business unit. A select set of silos became a focal point for the restructuring, with the goal of ensuring that employees transcended formal structure in cross-selling and in delivering holistic solutions that could differentiate the organization in the marketplace. Beyond information flow, the ONA also made it clear that the top 250 executives were not aware of the skills and expertise available through the network that could be leveraged in client work. Raising awareness at key points in the network became a critical precursor to increasing revenue-generating collaborations, bringing the best expertise to client projects, and boosting productivity through best-practice transfers.

While the company took a range of actions to align the network with strategic objectives, special attention was paid to leaders who the ONA revealed were overly central. That is, the ten most sought-out people in the network—all but one of whom were in the top ranks of the organization—had from twenty-four to fifty-one people coming to them frequently for information. This network imbalance made it hard for many employees to gain access to these leaders. Through no fault of their own, the leaders had become bottlenecks, causing delays in decision making and slowing down projects and sales efforts. They also represented substantial susceptibilities in the network in that removing just these ten people (less than 5 percent of the top three layers in the organization) decreased the number of revenue-producing collaborations in the network by 26 percent.

Clearly, the excessive demands made on this small set of leaders needed to be reduced in order for the organization to succeed in the new matrix structure. As a result, the company initiated four specific actions. First, the chief information officer implemented an expertise locator to help people find resources across the organization and established global solution teams so that subject-matter experts were leveraged across regional boundaries. Second, the chief financial officer redefined dollar thresholds so that pricing decisions could be made by lower-level employees. For instance, a team one level below the vice presidents was given decision rights regarding solutions and pricing, a move that dramatically reduced the time and effort it took to approve relatively small, low-risk projects. Third, educational sessions were held on such topics as service offerings, delivery experience for service offerings, and rules of engagement between regions and business lines in order to facilitate understanding across the organization about how to work in the new matrix structure (see Figure 1.1). Finally, the senior team worked to develop a culture of responsiveness and increased information flow down and across the hierarchy by encouraging people to return calls and e-mails within twenty-four hours regardless of the seeker’s title or position.

Although the firm took care to alleviate some of the relational demands on those at higher levels, it also realized that these highly connected leaders, given their influence, could help drive change. For example, as the leader of the newly formed Application Services unit, one of the largest global groups, Peggy Smith was well connected. Yet even within her own group’s network, she saw that people were not collaborating across regions. Instead of creating committees among those in certain positions within the formal structure—a common approach to repairing such collaboration problems—Peggy used the ONA results to identify highly connected people in various regions and then forged ties among them. This helped Peggy and her direct reports to rapidly and efficiently build awareness across regional boundaries of who knew what.

A second ONA, conducted six months later, showed that the network had become much more closely aligned with the strategic objectives set out for the matrix structure. First, collaboration was more evenly distributed and employees were able to get information they needed and decisions approved much more rapidly. Second, the group as a whole was getting greater leverage from its peripheral members, many of whom were in key client-facing roles. For example, the second ONA revealed a 17 percent increase in ties to and from account managers who had previously been on the network’s periphery. Not surprisingly, these new relationships had had a positive impact on client-service and account-penetration measures. Third, the network was now better integrated across functions and regions, an improvement crucial to the success of the matrix structure (see Figure 1.1). Specifically, employee collaborations across functions had increased by 13 percent and resulted in numerous examples of improved client service, sales, and best-practice transfer at these junctures.

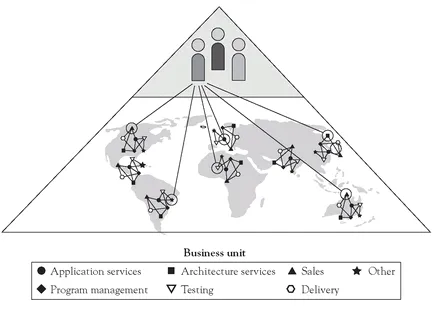

Figure 1.1. Facilitating a Matrix Structure Through Targeted Connectivity

In sum, ONA accelerated the company’s transformation from a branch-centric to a global operation. One highly central vice president indicated that “the ONA was helpful in realizing why we lacked nimbleness and quick turnaround times for RFPs or unsolicited proposals. Creating points of contact and information conduits across business lines and regions helped us assemble teams with needed skills, knowledge, and experience more efficiently, enabling faster time to market.” Results from the second ONA showed a 27 percent increase in sales collaborations of up to $500,000, a 15 percent increase in sales between $500,000 and $2 million, and a 9 percent increase in client sales between $2 million and $10 million. In aggregate, these results boosted the firm’s revenue by nearly 10 percent on an annualized basis.

What made this transition such a success was that leaders attended to both informal and formal structure. The network analysis played a crucial role in helping leaders—such as Peggy—build bridges much more rapidly to well-connected experts throughout the global organization. Equally important, it helped the organization see what would happen if key account managers left, and how to get better leverage out of high-end experts who had drifted to the fringe of the network.

But these and other changes to the network would be only temporary if not accompanied by changes to formal structure. Annual planning processes, project start-up practices, human resource processes, and technology—to name just a few—were all aspects of the formal organization that were shifted to create a context in which the right collaborations were more likely to occur and flourish over time. In this instance, the appropriate aspects of formal structure to consider were those that helped in the transition to a more client-centric, matrix-based structure. In other organizations—for example, those that thrive on process excellence and efficiency—very different structural elements must be in place to promote the right network configuration.

Network Archetypes and Value Propositions

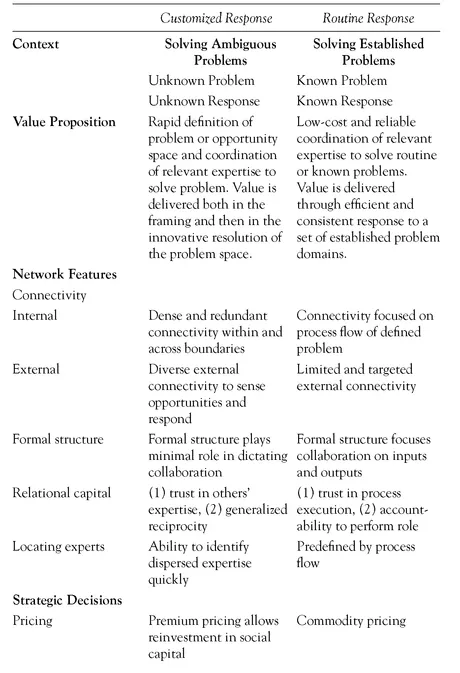

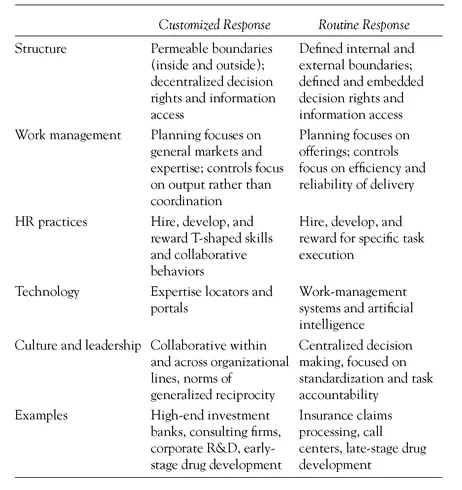

Networks enable organizations to do two things: recognize opportunities and challenges, and coordinate appropriate responses. But the kind of network an organization needs in order to be most effective and efficient will depend on its value proposition, its strategic objectives, and the nature of its work. Through our work in a wide range of industries, we have identified two network archetypes that characterize the two ends of the spectrum: the customized response network and the routine response network. These two kinds of networks are each suited for a specific value proposition and demand certain investments.

Customized response networks. These networks develop in order to define a problem or an opportunity rapidly and coordinate relevant expertise in response. They are “custom” in that the value of these networks derives from both the framing of a problem and the creation of an innovative resolution. Organizations obtaining value from customized response networks include strategy consulting firms, high-end investment banks, new-product development consultancies, and early-stage drug development.

Routine response networks. These networks operate best in environments where both problems and solutions are fairly well defined and predictable, and the work is standardized. Value is delivered through efficient and consistent responses to established problem domains. Insurance claims processing, call centers, and late-stage drug development, for instance, all require low-cost and reliable coordination of expertise to solve commonly occurring problems.

In Table 1.1 we have outlined both salient network characteristics and organizational decisions that must be made to support each kind of network. We now turn to case descriptions of both archetypes.

Table 1.1. Designing Value-Based Networks

Customized Response Case Study: Novartis

Novartis, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, won Federal Drug Administration approval in May 2001 for Gleevec, a breakthrough medication that arrests a life-threatening form of blood cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Gleevec, a tiny orange capsule, enjoyed the fastest approval ever granted by the FDA for a cancer drug and is considered revolutionary because of the way it treats CML. Traditional cancer therapies combat the disease through surgery or a combination of toxic drugs and radiation that destroy cancer cells as well as some normal cells. As a result, often patients are left feeling extremely weak and suffering from severe side effects. Gleevec is the first cancer drug that targets a cancer-producing molecule and fixes the genetic malfunction without harming healthy cells. “Our hope is to turn cancer into a chronic but treatable disease,” says Alex Matter, formerly head of Oncology Research at Novartis, who discovered the drug with his team of scientists.

Gleevec is the product of a customized response network. Alex Matter and his team challenged the traditional treatment of CML and created something new based on cutting-edge developments in gene therapy and the selective targeting of cancer-producing cells. The breakthrough drug that resulted from their efforts required what Dan Vasella, CEO of Novartis, described as innovation management—calling on a wide variety of internal and external expertise to define and solve the problem, challenging assumptions by engaging scientists across disciplines, and taking creative risks in both drug discovery and delivery.

The networks that created Gleevec were nowhere apparent on Novartis’s formal organization chart—in fact, diverse connections external to Novartis were altogether pivotal to the success of Gleevec. Before Novartis even existed, Matter worked at Ciba-Geigy in Switzerland and had been considering ways that kinases, or enzymes, might affect cancer growth by inhibiting cell proliferation. At the time, no one was pursuing the idea of inhibiting kinases as a type of treatment—most scientists thought it would be impossible.

But Matter persisted in seeking out scientists who could point the way to diseases that his team might target. He relied heavily on his external contacts—including Brian Druker and Tom Roberts at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston—to keep abreast of cutting-edge ideas in fields relevant to cancer treatment. Druker, a medical oncologist, knew that CML was the most promising cancer for research using the approach that Matter was contemplating. It was the only cancer in which the genetic cause had been scientifically established. Druker’s research interests overlapped with Matter’s and provided fertile territory for exploring a new way to treat cancer. Later, when Matter and his team were at Novartis and had discovered and tested in animal trials a compound effective against CML, external connections became critic...

Table of contents

- Praise

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One - ALIGNMENT

- Part Two - EXECUTION

- Part Three - ADAPTATION

- About the Authors

- Notes

- Index