eBook - ePub

Managing Credit Risk

The Great Challenge for Global Financial Markets

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Credit Risk

The Great Challenge for Global Financial Markets

About this book

Managing Credit Risk, Second Edition opens with a detailed discussion of today's global credit markets—touching on everything from the emergence of hedge funds as major players to the growing influence of rating agencies. After gaining a firm understanding of these issues, you'll be introduced to some of the most effective credit risk management tools, techniques, and vehicles currently available. If you need to keep up with the constant changes in the world of credit risk management, this book will show you how.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Credit Risk by John B. Caouette,Paul Narayanan,Robert Nimmo,Edward I. Altman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Credit Risk

The Great Challenge For The Global Economy

Moderate leverage undoubtedly boosts the capital stock and the level of output . . . the greater the degree of leverage in any economy, the greater its vulnerability to unexpected shortfalls in demand and mistakes.

—Alan Greenspan, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2002

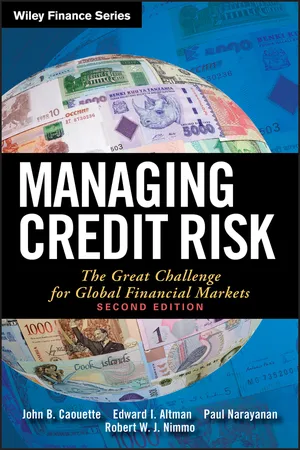

In recent decades, credit risk has become pervasive in the United States and throughout the world. The U.S. Treasury borrows to keep the federal government afloat, and local water districts borrow to construct new treatment plants. Corporations borrow to make acquisitions and to grow, small businesses borrow to expand their capacity, and millions of individuals use credit to buy homes, cars, boats, clothing, and food. The dramatic growth in U.S. borrowing by all segments of the society is illustrated in Figure 1.1, which suggests the scale of this credit explosion.

FIGURE 1.1 Revolving Debt in the United States, 1968–2006

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2006).

An element of credit risk exists whenever an individual takes a product or service without making immediate payment for it. Telephone companies and electric utilities accept credit risk from all their subscribers. Credit card issuers take this risk with all their cardholders, as do mortgage lenders with their borrowers. In the corporate sector, businesses in virtually every industry sell to customers on some kind of terms. Every time they do so, they accept credit risk. The credit risk assumed may be for a few hours or for a hundred years.

Meanwhile, the use of credit became a major factor of other countries as well. Europe has seen a significant increase in leverage by corporations and individuals, particularly in Britain where the patterns are similar to those in the United States. Emerging markets have also joined the bandwagon as both countries and their corporations and individuals have come to see credit as a powerful tool for economic progress. Meanwhile the capital markets have provided many more ways for these institutions and individuals to borrow.

CHANGING ATTITUDES TOWARD CREDIT

The credit explosion has been accompanied—and accelerated—by a dramatic shift in public attitudes. When Shakespeare’s Polonius advised his son, “Neither a borrower nor a lender be,” he was voicing the wisdom of his time. He reasoned that “loan oft loses both itself and friend, and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.” Such advice—whatever its merits were in the Elizabethan age—has been drowned out by the contrary opinion. And Polonius may have been wrong about friends, too. Banks continue to court borrowers who caused them to lose money in the past! And if borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry, no one seems to mind. Any shame that once attached to the use of credit has vanished.

Even the words we use to describe credit reflect a major shift in attitude. The word debtor still carries connotations of misery and shame—an echo of Dickensian debtors’ prisons. The word borrower, likewise, may still call to mind a pathetic figure going hat in hand to a powerful and possibly scornful banker. But today, we no longer need to see ourselves as debtors or borrowers. We can think of ourselves as people using leverage—a word with entirely different connotations. Leverage suggests that we are clever enough and skillful enough to employ a tool that multiplies our power. And using leverage leaves the rest of our identity intact—we do not become leveragors in the same way that we become debtors. Using leverage is something to boast about, not something to conceal. Today many people see credit as an entitlement.

From many directions, in fact, Americans are bombarded with invitations to increase their borrowing. Automobile manufacturers attract buyers with low rates on auto loans and offer leases with easy terms to customers who cannot afford a down payment. Retailers entice consumers to open charge accounts by offering discounts on their first purchases. Credit card issuers cram Americans’ mailboxes with competing offers. Even credit-impaired individuals—those who once sought the protection of the bankruptcy court—are soon viewed as good credit risks because they are now debt free (Philadelphia Inquirer 1996, D-1). Indeed, if there is still shame in any type of consumer transaction, it currently attaches to cash. Many may have seen recent commercials from Visa regarding the use of cash by a customer as slowing down the progress of purchasing in a busy market circumstance. The merchant who insists that you pay for a purchase in cash may well be impugning your integrity.

This shift in attitude is just as visible in the commercial sphere. CEOs and CFOs are paid handsomely to find other people’s money for their companies to leverage. The stock market, which shows little taste for underleveraged companies, exerts steady pressure on public companies to put an appropriate level of debt on their balance sheets. Meanwhile, pension funds and insurance companies are the major investors in hedge funds and private equity firms who vie with one another to lend money to finance leveraged buyouts.

High-yield (or junk) bonds have existed for decades, but they were once symptomatic of “fallen angels”—formerly prosperous companies whose fortunes had declined. Today, however, issuing junk bonds is seen as a perfectly respectable strategy for companies lacking access to lower-cost forms of credit.

Even bankruptcy—at least the Chapter 11 variety—has lost much of its sting. Once avoided as a shameful and potentially career-ending debacle, bankruptcy is now widely accepted as a reasonable strategic option. Many companies have sought Chapter 11 bankruptcy as a way to obtain financing for growth, to extricate themselves from burdensome contractual obligations, or to avoid making payments that they deemed inconvenient to suppliers, employees, or others. Meanwhile, individuals who choose personal bankruptcy know that their credit can be resurrected in a mere 10 years—or as little as three to five years if they have completed a repayment plan under a Chapter 13 filing (U.S. Courts, Bankruptcy Basics). Meanwhile in the United Kingdom, the Enterprise Bill 2002 enables a first-time bankruptcy to be discharged after only one year.

The spectacle of Orange County’s financial woes suggests that attitudes toward bankruptcy have changed in the public sphere, too. Neither the county’s population nor its leaders showed much embarrassment or sense of urgency when it defaulted on its obligations in 1994 because of losses exceeding $1.6 billion that it had suffered in derivative “investments.” Apart from front-page stories like this, credit quality, as assessed by the rating agencies, has followed a downward trend in the public finance market. At the same time, state and local government entities have accessed the public debt market in growing numbers over the past 35 years. Seventeen states had a triple-A credit rating in 1970. Just nine states could lay claim to this distinction in 2006 (Moody’s and S&P reports). The causes for the erosion of municipal credit quality—taxpayer revolts, mismanagement, and, in the cities, declining tax revenues and inflexible labor costs—may be endemic to the municipal arena, but the decline is in keeping with trends visible in the corporate market, too.

Attitudes towards the use of credit and the importance of maintaining a reputation as a conservative and careful borrower have changed. For example, California, our largest state, and the world’s sixth largest economy, is a particularly interesting case. Triple-A rated in the early 1990s, the state’s GOs (general obligations) began a drop in the mid-1990s to AA and then into freefall in 2001–2003 to reach Baa before a more recent uptick to A1. Similar attitudes in the corporate sector are evident such as when U.S. Air went bankrupt simply to renegotiate long-term leverage uses of aircraft.

MORE NATIONS BORROW

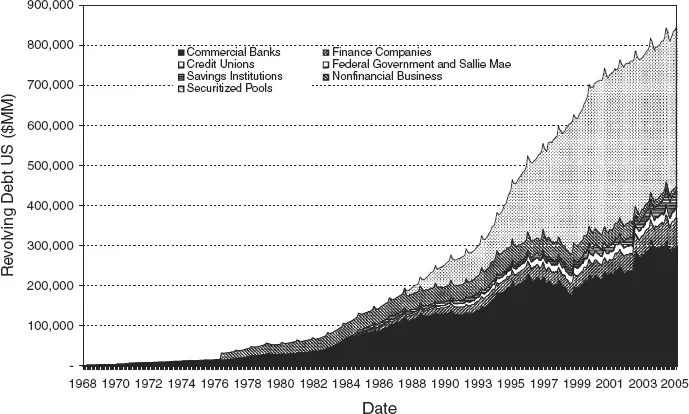

The appetite for borrowing is truly global in scope. Sovereign obligors have come to the international financial markets in ever-greater numbers. Figure 1.2 shows the growth in rated sovereign borrowers in the period 1975–2006.

FIGURE 1.2 Sovereigns Rated by Standard & Poor’s, 1975–2006

Source: Standard & Poor’s The Future of Credit Ratings (2006).

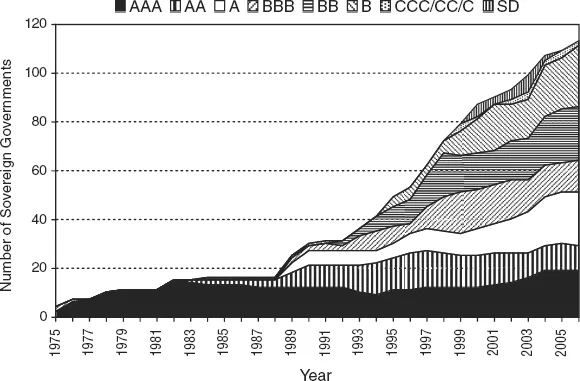

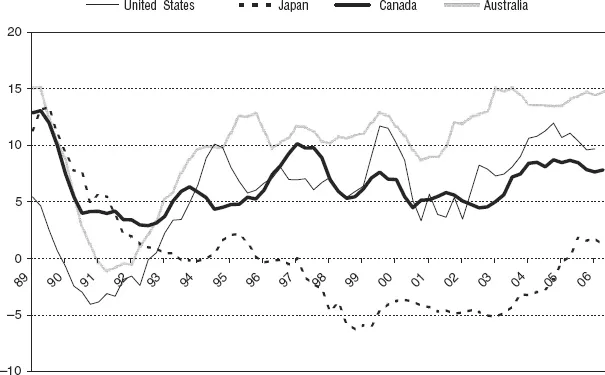

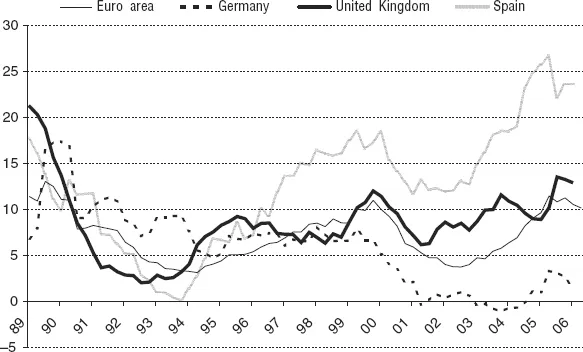

What is particularly interesting in this table is the growth in the number of countries that now are rated by the global rating agencies. This is a clear indication of the importance of access to the capital markets by countries all over the world. As Figure 1.3, Figure 1.4, and Figure 1.5 show, developed countries have increasingly relied on public and private debt.

FIGURE 1.3 Public Debt in Developed Economies

Source: Organisation for the Economic Co-operation and Development (2006).

FIGURE 1.4 Credit Growth (private domestic credit)

Source: Bank for International Settlements, Annual Report 2007.

FIGURE 1.5 Credit growth in Europe (private domestic credit)

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2006).

A new trend in many other developed and developing countries is privatization. Traditionally, infrastructure projects such as roads or bridges were financed by the government. This is changing rapidly. In the United Kingdom, for example, under the Private Finance Initiative, major projects, and even defense-related activities, are being shifted to private sector operators under long-term contracts remunerated by service charges. This trend has accelerated into the European Union, Australia, and in the United States.

Deregulated domestic financial institutions and corporations in emerging markets have been able to tap into foreign capital to finance domestic growth.

In emerging economies, the growth in borrowing is not limited to corporations and governments. Consumers in many regions are quickly learning how to pay with plastic. In developing countries from Argentina to Thailand, credit card debt is rapidly expanding.

MORE LEVERAGE, MORE OPPORTUNITY, AND MORE RISK

Without question, the availability—and acceptability—of credit facilitates modern life and fuels the economy. Credit enables individuals of even modest means to buy homes, cars and consumer goods, and this, in turn, creates employment and increases economic opportunity. Credit enables businesses to grow and prosper. Governmental agencies all over the world use credit to build infrastructure that they cannot fund from annual budgets. In the United States, the municipal bond market is huge, allowing states, cities, towns, and their agencies the meet the public’s needs for schools, hospital, and roads.

Hermando de Soto in his book The Mystery of Capital has argued that the ability to leverage for both individuals and commercial enterprises is the most important factor in understanding why some economies are developed and others are not. In the United States, we have taken this leveraging concept to new levels and Europe is not far behind. The economies in the United States and in Europe have become both large and diversified. This means that leverage is needed to marshal the investment required to operate the economy and to develop new products and services. The diversification of the economies—which is a huge change from what existed 100 or even 50 years earlier—makes the economies much more stable and therefore much less risky from a systemic basis. So it should be no surprise that the credit markets in the developed world have grown to massive proportions and that countries in the developing world are looking for ways to emulate it.

The credit markets clearly have grown. We are more leveraged than we used to be. Credit facilities are on offer everywhere. Whether you are a treasurer looking to finance a new business, a local government wishing to build a new school or an individual hoping to buy a new home, you have many options available to you. Many more options than you would have had just a few years ago. Many observers of this phenomenon see big risks inherent in this situation. Warnings of upcoming doom are familiar topics in our newspapers and the subject for more than a few books. But most of the doomsayer’s just p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Credit Risk

- Chapter 2: Credit Culture

- Chapter 3: Classic Industry Players

- Chapter 4: The Portfolio Managers

- Chapter 5: Structural Hubs

- Chapter 6: The Rating Agencies

- Chapter 7: Classic Credit Analysis

- Chapter 8: Asset-Based Lending and Lease Finance

- Chapter 9: Introduction to Credit Risk Models

- Chapter 10: Credit Risk Models Based upon Accounting Data and Market Values

- Chapter 11: Corporate Credit Risk Models Based on Stock Price

- Chapter 12: Consumer Finance Models

- Chapter 13: Credit Models for Small Business, Real Estate, and Financial Institutions

- Chapter 14: Testing and Implementation of Credit Risk Models

- Chapter 15: About Corporate Default Rates

- Chapter 16: Default Recovery Rates and LGD in Credit Risk Modeling and Practice

- Chapter 17: Credit Risk Migration

- Chapter 18: Introduction to Portfolio Approaches

- Chapter 19: Economic Capital and Capital Allocation

- Chapter 20: Application of Portfolio Approaches

- Chapter 21: Credit Derivatives

- Chapter 22: Counter Party Risk

- Chapter 23: Country Risk Models

- Chapter 24: Structured Finance

- Chapter 25: New Markets, New Players, New Ways to Play

- Chapter 26: Market Chaos and a Reversion to the Mean

- Appendix

- Index