![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Tomography 1

1.1. Introduction

Tomographic imaging systems are designed to analyze the structure and composition of objects by examining them with waves or radiation and by calculating virtual cross-sections through them. They cover all imaging techniques that permit the mapping of one or more physical parameters across one or more planes. In this book, we are mainly interested in calculated, or computer-aided, tomography, in which the final image of the spatial distribution of a parameter is calculated from measurements of the radiation that is emitted, transmitted, or reflected by the object. In combination with the electronic measurement system, the processing of the collected information thus plays a crucial role in the production of the final image. Tomography complements the range of imaging instruments dedicated to observation, such as radar, sonar, lidar, echograph, and seismograph. Currently, these instruments are mostly used to detect or localize an object, for instance an airplane by its echo on a radar screen, or to measure heights and thicknesses, for instance of the earth’s surface or of a geological layer. They mainly rely on depth imaging techniques, which are described in another book in the French version of this series [GAL 02]. By contrast, tomographic systems calculate the value of the respective physical parameter at all vertices of the grid that serves the spatial encoding of the image. An important part of imaging systems such as cameras, camcorders, or microscopes is the sensor that directly delivers the observed image. In tomography, the sensor performs indirect measurements of the image by detecting the radiation with which the object is examined. These measurements are described by the radiation transport equations, which lead to what mathematicians call the direct problem, i.e. the measurement or signal equation. To obtain the final image, appropriate algorithms are applied to solve this equation and to reconstruct the virtual cross-sections. The reconstruction thus solves the inverse problem [OFT 99]. Tomography therefore yields the desired image only indirectly by calculation.

1.2. Observing contrasts

A broad range of physical phenomena may be exploited to examine objects. Electromagnetic waves, acoustic waves, or photonic radiation are used to carry the information to the sensor. The choice of the exploited physical phenomenon and of the associated imaging instrument depends on the desired contrast, which must assure a good discrimination between the different structures present in the objects. This differentiation is characterized by its specificity, i.e. by its ability to discriminate between inconsequential normal structures and abnormal structures, and by its sensitivity, i.e. its capacity for measuring the weakest possible intensity level of relevant abnormal structures. In medical imaging, for example, tumors are characterized by a metabolic hyperactivity, which leads to a marked increase in glucose consumption. A radioactive marker such as fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) enables detection of this increase in the metabolism, but it is not absolutely specific, since other phenomena, such as inflammation, also entail a local increase in glucose consumption. Therefore, the physician must interpret the physical measurement in the context of the results of other clinical examinations.

It is preferable to use coherent radiation whenever possible, which is the case for ultrasound, microwaves, laser radiation, and optical waves. Coherent radiation enables measurement not only of its attenuation but also of its dephasing. The latter enables association of a depth with the measured information, because the propagation time difference results in dephasing. Each material is characterized by its attenuation coefficient and its refractive index, which describe the speed of propagation of waves in the material. In diffraction tomography, we essentially aim to reconstruct the surfaces of the interfaces between materials with different indices. In materials with complex structures, however, the multiple interferences rapidly render the phase information unusable. Moreover, sources of coherent radiation, such as lasers, are often more expensive. With X-rays, only phase contrast phenomena that are linked to the spatial coherence of photons are currently observable, using microfocus sources or synchrotrons. This concept of spatial coherence reflects the fact that an interference phenomenon may only be observed behind two slits if they are separated by less than the coherence length. In such a situation, a photon interferes solely with itself. Truly coherent X-ray sources, such as the X-FEL (X-ray free electron laser), are only emerging.

In the case of non-coherent radiation, like γ-rays, and in most cases of X-ray imaging and optical imaging with conventional light sources, each material is mainly characterized by its attenuation and diffusion coefficients. Elastic or Rayleigh diffusion is distinguished from Compton diffusion, which results from inelastic photon—electron collisions. In γ- and X-ray imaging, we try to keep attenuated direct radiation only, since, in contrast to diffused radiation, it propagates along a straight line and thus enables us to obtain a very high spatial resolution. The attenuation coefficients reflect, in the first approximation, the density of the traversed material. Diffusion tomography is, for instance, used in infrared imaging to study blood and its degree of oxygenation. Since diffusion spreads light in all directions, the spatial resolution of such systems is limited.

Having looked at the interaction between radiation and matter, we now consider the principle of generating radiation. We distinguish between active and passive systems. In the former, the source of radiation is controlled by an external generator that is activated at the moment of measurement. The object is explored by direct interrogation if the generated incident radiation and the emerging measured radiation are of the same type. This is the case in, for example, X-ray, optical, microwave, and ultrasound imaging. The obtained contrast consequently corresponds to propagation parameters of the radiation. For these active systems with direct interrogation, we distinguish measurement systems based on reflection or backscattering, where the emerging radiation is measured on the side of the object on which the generator is placed, and measurement systems based on transmission, where the radiation is measured on the opposite side. The choice depends on the type of radiation employed and on constraints linked to the overall dimensions of the object. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a system with direct interrogation, since the incident radiation and the emerging radiation are both radiofrequency waves. However, the temporal variations of the excitation and received signals are very different. The object may also be explored by indirect interrogation, which means that the generated incident radiation and the emerging measured radiation are of different types. This is the case in fluorescence imaging, where the incident wave produces fluorescent light with a different wavelength (see Chapter 6). The observed contrast corresponds in this case to the concentration of the emitter.

In contrast to active systems, passive systems rely on internal sources of radiation, which are inside the analyzed matter or patient. This is the case in magneto- and electro-encephalography (MEG and EEG), where the current dipoles linked to synaptic activity are the sources. This is also the case in nuclear emission or photoluminescence tomography, where the tracer concentration in tissues or materials is measured. The observed contrast again corresponds to the concentration of the emitter. Factors such as attenuation and diffusion of the emitted radiation consequently lead to errors in the measurements.

In these different systems, the contrasts may be natural or artificial. Artificial contrasts correspond to the injection of contrast agents, such as agents based on iodine in X-ray imaging and gadolinium in MRI, and of specific tracers dedicated to passive systems, such as tracers based on radioisotopes and fluorescence. Within the new field of nanomedicine, new activatable markers are investigated, such as luminescent or fluorescent markers, which become active when the molecule is in a given chemical environment, exploiting for instance the quenching effect, or when the molecule is activated or dissociated by an external signal.

Finally, studying the kinetics of contrasts provides complementary information, such as uptake and redistribution time constants of radioactive compounds. Moreover, multispectral studies enable characterization of flow velocity by the Doppler effect, and dual-energy imaging enables decomposition of matter into two reference materials such as water and bone, thus enhancing the contrast.

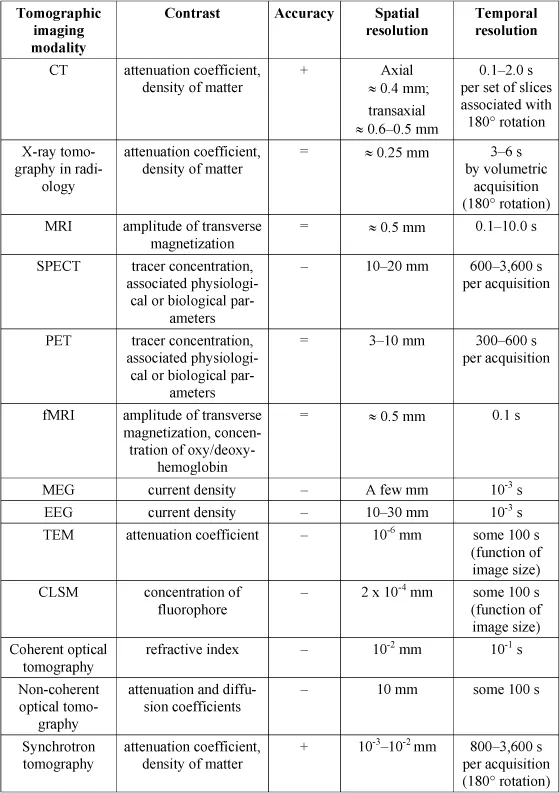

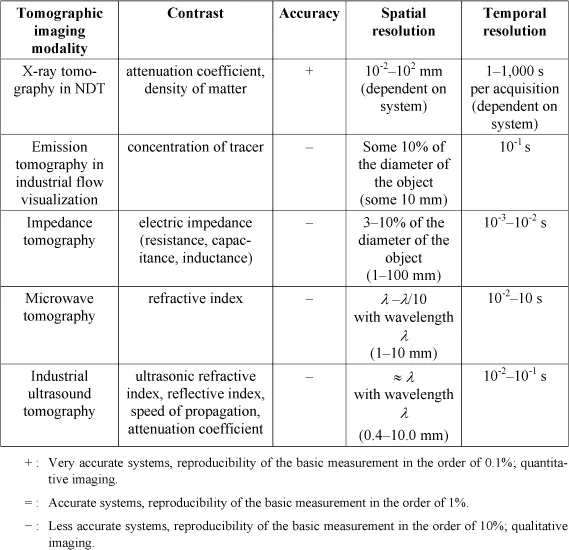

In Table 1.1, the principal tomographic imaging modalities are listed, including in particular those addressed in this book. In the second column, entitled “contrast”, the physical parameter visualized by each modality is stated. This parameter enables in certain cases, as in functional imaging, the calculation of physiological or biological parameters via a model which describes the interaction of the tracer with the organism. In the third column, we propose a classification of these systems according to their accuracy. We differentiate between very accurate systems, which are marked by + and may reach a reproducibility of the basic measurement of 0.1%, thus permitting quantitative imaging; accurate systems, which are marked by = and attain a reproducibility of the order of 1%; and less accurate systems, which are marked by — and provide a reproducibility in the order of 10%, thus allowing qualitative imaging only. Finally, in the fourth and fifth columns, typical orders of magnitude are given for the spatial and temporal resolution delivered by these systems. In view of the considerable diversity of existing systems, they primarily allow a distinction between systems with a high spatial resolution and systems with a high temporal resolution. They also illustrate the discussion in section 1.3. The spatial and temporal resolutions are often conflicting parameters that depend on how the data acquisition and the image reconstruction are configured. For example, increasing the time of exposure improves the signal-to-noise ratio and thus accuracy at the expense of temporal resolution. Likewise, spatial smoothing alleviates the effect of noise and improves statistical reproducibility at the expense of spatial resolution. Another important parameter is the sensitivity of the imaging system. For instance, nuclear imaging systems are very sensitive and are able to detect traces of radioisotopes, but need very long acquisition times to reach a good signal-to-noise ratio. Therefore, the accuracy is often limited. The existence of disturbing effects often corrupts the measurement in tomographic imaging and makes it difficult to attain an absolute quantification. We are then satisfied with a relative quantification, according to the accuracy of the measurement.

In most cases, the interaction between radiation and matter is accompanied by energy deposition, which may be associated with diverse phenomena, such as a local increase in thermal agitation, a change of state, ionization of atoms, and breaking of chemical bonds. Improving image quality in terms of contrast- or signal-to-noise ratio unavoidably leads to an increase in the applied dose. In medical imaging, a compromise has to be found to assure that image quality is compatible with the demands of the physicians and the dose tolerated by the patient. After stopping irradiation, stored energy may be dissipated by returning to equilibrium, by thermal dissipation, or by biological mechanisms that try to repair or replace the defective elements.

1.3. Localization in space and time

Tomographic systems provide images, i.e. a set of samples of a quantity on a spatial grid. When this grid is two-dimensional (2D) and associated with the plane of a cross-section, we speak of 2D imaging, where each sample represents a pixel. When the grid is three-dimensional (3D) and associated with a volume, we speak of 3D imaging, where each element of the volume is called a voxel. When the measurement system provides a single image at a given moment in time, the ...